To Choose or Be Chosen by Gene Ciarlo

Christianity is being shaken to its foundations in our time. The decline started not long after Vatican Council II, those halcyon days when Pope John XXIII challenged the critics and moved to breathe new life into Roman Catholicism, to open the windows and send fresh air streaming into the decrepit, stagnant, and dogma-Curia-structure-locked church.

The routine that Roman Catholics were treading at the time was surreptitiously molding and smoldering, in spite of the façade of awe-inspiring throngs of Roman Catholics attending Sunday Mass and bowing deeply to the glitter of devotional life that was part and parcel of Roman Catholicism. But was it all chimera, a façade, a mindless formality and soulless routine? The answer to that question is playing out as we speak. If there was little heart and no soul in the routine, with the passage of time and enlightenment, with the dawn and the light of day, decline was inevitable.

Decline is in the offing, with lots of hand-wringing on the part of the hierarchy and other parties with vested interest in the salvation of the institution. Today, not only in the Catholic Church but in all the churches of Christendom, the death knell is sounding. Am I being overly dramatic? I’m looking at the year 2040, when the people whom we see now filling the pews in our churches are no longer there. And neither is anyone else.

The structures of religion as we know them, affecting people’s thoughts and actions, must change radically or we are doomed to a gradual disintegration of religious beliefs and practices until there is only a remnant left that will have no influence on what happens in our society. Yet I am convinced that the world needs an authentic spirituality, an offering to our wounded humanity that can be found in a radically revived Christianity.

I am advocating change-from-the-roots in the way Christianity presents itself in order to make a significant and essential impact on the world and its politics, its social structure, its international relations, if we are to ignite the spark of goodness that eternally resides in all of humanity. Humanity needs a catalyst if our goodness is to blossom, because the forces of evil in the world must be countered by something which can bring out the best in us. Christianity, and more specifically the Catholic Church, should, could, ought to be able to do that if we would only speak to our times in an intelligent, reasonable, progressive way, taking into account the intelligence of people and their need for reasonableness and not rote. Thus the desideratum: Thoughtfulness and not habit; intellect and not instinct; wisdom, understanding, conviction, and determination in a ruthless world.

It is common knowledge that organized religion, generally speaking, is on the decline, at least in the western hemisphere. Is there a secular counterpart to replace it for the sake of harmony and order, goodness and peace among nations and peoples? Religions, implying lofty ideals that raise people above the pitfalls of our nature, are intended to provide a moral compass, shedding light on a way to go, a path to follow. Most religions are about compassion, understanding, mercy, kindness, harmony, and peace. The big question that I struggle with and probe is this: Is human nature, devoid of religion, competent and good enough to stand alone in the struggle for righteousness and goodness on this earth which, for better or worse, we dominate and try desperately to control?

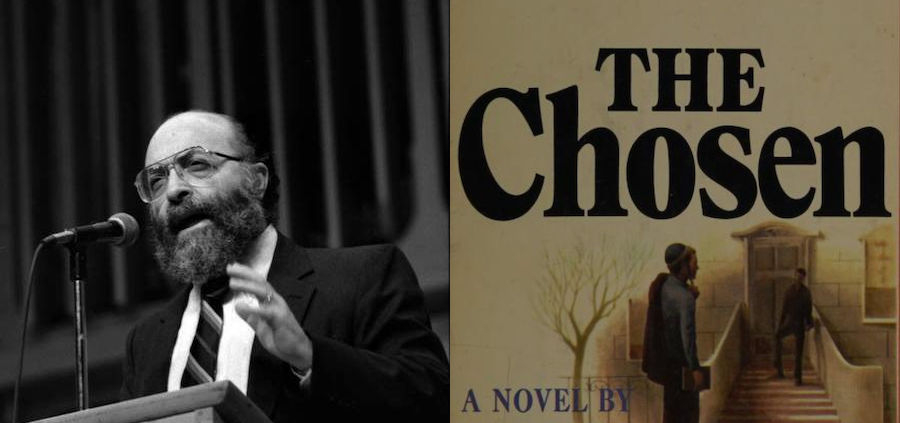

The Chosen, a novel by Chaim Potok written in 1967, speaks to me about religious belief and practice at this critical and crucial time in the life of the Catholic Church and helps to answer my question. The story weighs the value of religion in our contemporary age of secularism and relative truth. The author of this tale was no ordinarily talented writer. Potok bore the dual distinction of being a very erudite and cultured rabbi as well as a great scholar of English literature. The plot is centered on Jewish life through and through, with deep insights into Hasidic culture in Brooklyn, New York, around the time of World War II. It reflects scholarliness and great insight into human nature and the varied lifestyles of faithful Jews living in Brooklyn during the hard times before Israel secured a homeland.

After reflecting seriously on the story that the rabbi tells, I am led to confess that spiritual life resides in the marrow of humanity without benefit of religious belief and practice. Religion fuels and assists that fundamental, built-in flame of goodness that perhaps may be called godliness. What manifests itself to me in The Chosen is the goodness of people, with or without religion. It is goodness not created by religious fervor but perchance assisted by religious convictions and lifestyle. Sometimes while reading I was struck by the “games” that religion plays; other times, I was inspired by the height to which religious life can raise a person. People who own a religion and are faithful to it live a paradox, an enigma.

The heart and soul of The Chosen focuses on two teenage boys, Reuven and Daniel, both Orthodox Jews, both belonging to Hasidic sects that differ greatly in their beliefs and practices. Regardless of their strong differences and occasional clashes, the story of these boys is told with great tenderness, warmth, and compassion.

Reuven and Daniel become the best of friends, but only in the course of time, since an initial baseball-game disaster leaves them not only rivals but enemies. Reuven is the more liberal of the two, with a loving father, Rabbi Malter. Daniel, bearing sidelocks and a black coat, has the strict and revered Hasidic Rabbi Saunders as a father, severe not only in appearance but in total bearing, word, and deed. In one powerful lesson, the conservative Rabbi Saunders makes known to Reuven his whole philosophy of life and theology:

A man is born into this world with only a tiny spark of goodness in him. The spark is God, it is the soul: the rest is ugliness and evil, a shell. The spark must be guarded like a treasure, it must be nurtured, it must be fanned into flame. It must learn to seek out other sparks, it must dominate the shell. Anything can be a shell, Reuven. Anything. Indifference, laziness, brutality, and genius. Yes, even a great mind can be a shell and choke the spark.

Is that a common truth and belief? Are we born with only a tiny spark of goodness or are we thoroughly good at birth, only to become corrupted by the cruelty of life in the world?

The story continues. Reb Saunders is deeply saddened because he is certain that Daniel—scholarly, winsome, intelligent, loving, compassionate—has brilliance but no soul. And what good is it to gain the whole world but lose—but never have—a soul?

Reuven, the Master of the Universe blessed me with a brilliant son. And he cursed me with all the problems of raising him. . . . Not a smart son, Reuven, but a brilliant son, a Daniel, a boy with a mind like a jewel . . . a mind in a body without a soul.

The curtain falls; silence ensues. Reb Saunders is convinced that his son doesn’t have a spark of goodness which is God to nurture. The presumption here is that the grace-filled human condition into which I believe we are born is not a reality, is not true. We are not born full of grace.

My own thoughts here intervene. Religion is supposed to nurture the soul, that spark of goodness in humanity. But so often it is a façade, a cloak, a comfort and salve, a safe port and refuge for multitudes in the midst of the storms of life. In Christianity, that kind of superficial religion is what spawned the Inquisition and the Crusades, and in Islam it presently claims an untold number of lives in Iraq, in Sudan, Afghanistan, and throughout the Middle East. It is often described as radical or extreme, but I consider those terms euphemisms for warped, myopic, and totally godless. It is easy in such environments to nod vigorous assent to Rabbi Saunders’s conviction that we are born with only a tiny spark of goodness. But I contend that we are born with a flame, a bonfire of goodness that is constantly attacked on every side from cradle to grave. Nature and nurture play out their hands.

Earlier in the novel, Rabbi Malter is telling Reuven the story of how Hasidic Judaism came to be. He speaks of a charismatic teacher who went about preaching his idea of God’s gift to Abraham, his style of the faith:

The Ba’al Shem Tov . . . believed that no man is so sinful that he cannot be purified by love and understanding. He also believed—and here is where he brought down upon himself the rage of the learned rabbis—that the study of Talmud was not very important, that there need not be fixed times for prayers, that God could be worshiped through a sincere heart, through joy and singing and dancing. In other words, Reuven, he opposed any form of mechanical religion. . . . Before the end of the century, about half of eastern European Jewry consisted of Hasidim, as his followers were called, pious ones. So great was the need of the masses for a new way to approach God.

Every religion has had its moments of purification, times when a charismatic figure steps forward and declares that we have to take another look at our beginnings, at the founder’s words, deeds, and intentions. Pope John XXIII and Vatican Council II spoke of just such a renewal. And long before him Martin Luther and others became fed up with the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church and made clear their intentions to purify at least their corner of the world. Throughout history, change has been a purifying force but also a source of controversy and division. Positive-minded thinkers like to call it “creative tension.” But it can also be a cause of division, hatred, and bloodshed in the name of God, in the name of the Master of the Universe, in the name of religion.

Here is Daniel, the brilliant mind without a soul, speaking to Reuven about his father:

I think he’s a great man. I respect him and trust him completely, which is why I think I can live with his silence. I don’t know why I trust him, but I do. And I pity him, too. Intellectually, he’s trapped. He was born trapped. I don’t ever want to be trapped the way he’s trapped. I want to be able to breathe, to think what I want to think, to say the things I want to say. I’m trapped now, too. Do you know what it’s like to be trapped? . . . My mind cries to get out of it. But I can’t. Not now. One day I will, though. I’ll want you around on that day, friend. I’ll need you around on that day.

Reuven is there when this happens:

Then I sat and listened to Danny cry. He held his face in his hands, and his sobs tore apart the silence of the room and racked his body. I went over to him and put my hand on his shoulder and felt him trembling and crying. And then I was crying too, crying with Danny, silently, for his pain and for the years of his suffering, knowing that I loved him, and not knowing whether I hated or loved the long, anguished years of his life. . . . I watched the sun set. The evening spread itself slowly across the sky.

The story of religion with its wars, vis-à-vis spirituality with its peace, will go on until there is no need for religion, no need for sacraments and signs of God. The struggle will be over. In the meantime, new religions keep popping up in abandoned stores, old warehouses, and around kitchen tables. They are all searching for the reign of God—and look, there it is, within you (Luke 17:21). ♦

Gene Ciarlo is a priest no longer active in the ministry. Ordained from the American College, University of Louvain, Belgium, he spent most of his ministry in parish life. After receiving a master’s degree in liturgical studies from Notre Dame University he returned to his alma mater in Louvain as director of liturgy and homiletics. Gene lives in Vermont, where everything is gracefully green when it is not solemnly white.

Outstanding Fr. Ciarlo …just what I needed along my journey in my 70’s. Life is too short for a hollow faith.

Thank You