Looking for Miss Annie Vickers by Nicole d’Entremont

When I was 23, I went to Selma, Alabama, to participate in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March. Every year around this time, I think of Selma and what I learned in that small town. Miss Annie Vickers will come back to me, although I’ve thought of her often in these intervening years.

This past October I turned 80, so I am probably older now than she was then, but she is always ageless in my memory. I see her snipping flowers by her fence. I see her beckoning gesture. But ultimately, it is the puzzle (for me then) and ardor of her words that gets to me, that makes me pause and wonder. So I’ll do now what writers do in my situation: put words on a page to nose their way around a dark room, bumping into and collecting bits of life, making a collage of fragments, seeking coherence.

♦ ♦ ♦

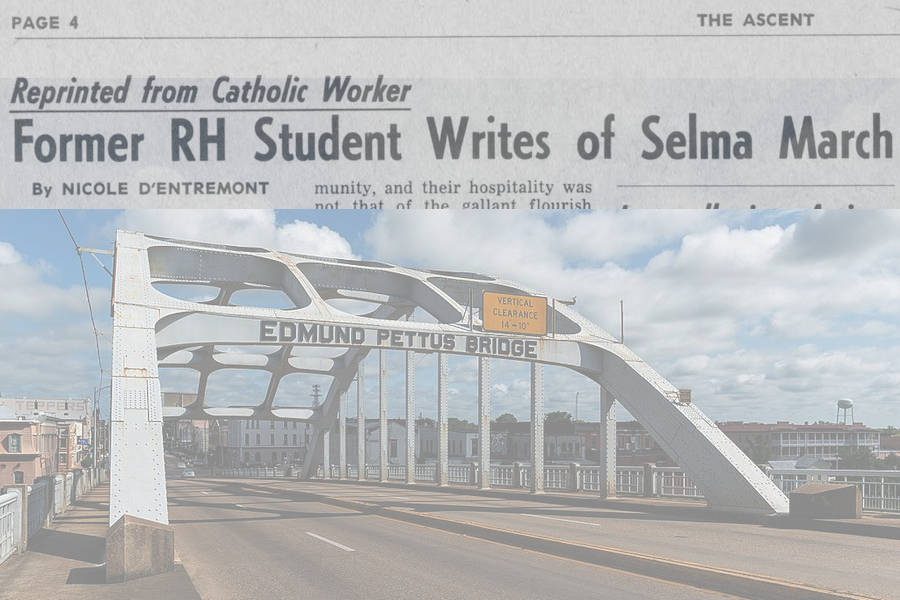

By 1965, I had been working at the Catholic Worker House on Chrystie Street in New York City for a year. I felt myself a seasoned old hand around the Lower East Side and ready to take on anything. I asked Dorothy Day if she would give me and my traveling companion, Sean Calloway, money for round trip bus tickets to Montgomery, Alabama. I wanted to write about Selma, what had happened there on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. I wanted to see what was going on now and what was to happen next. She gave us the money without question. I was grateful she had faith in me. I wanted to write a good story, one worthy of the pages of the Catholic Worker.

On March 17th, Sean and I presented ourselves, along with sleeping bags and backpacks, to the New York City Port Authority ticket agent where I purchased two round-trip bus tickets to Montgomery, Alabama. The agent glanced over at Sean leaning against a pillar with our gear on the floor and then back at me. Palming the money I pushed under the grate, eyes down (was he smiling?), he asked in a slow drawl, “Y’all wanna buy life insurance?” I declined. Returning to Sean with our tickets, I told him about the teller’s comment and we laughed. I also remember wishing Sean hadn’t decided to grow a beard for this trip.

We rode all day and through the night, arriving in Montgomery the next day. A fellow Catholic Worker who knew that we were coming met us and, having borrowed a car, drove us back the 54 miles to Selma. First stop: Brown Chapel and James Orange.

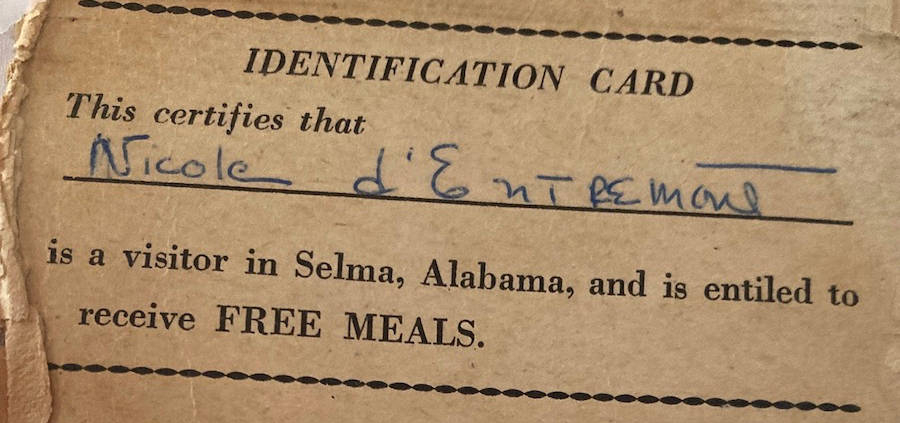

Orange was impressive, a large black man, older than us but not by much, I think now, in retrospect. He wore the Southern, civil rights–worker uniform of faded blue bib overalls and welcomed us, inviting us to sit in a pew with other white volunteers already assembled. We were being oriented. He introduced himself and said he worked for the King Construction Company. They were in the process of rebuilding the South. With these words and song, always song, we were welcomed to Selma, Alabama. We were each given an ID card, one I have kept in my possession, now, for 58 years.

In Selma, of course, no white people arriving could stay in the white section of town. We were “outside agitators,” and that was the polite term. I stayed with Mr. and Mrs. Edward Bell and their five girls in the Carver Homes right next to Brown Chapel. My 80-year-old self hopes I was polite and expressed my gratitude more than once for their hospitality. I don’t know where Mr. and Mrs. Bell and their five girls slept, but I know I was in a neat bedroom with a big double bed in the small apartment dwelling. There were pictures of family on the bedroom dresser. I slept there between demonstrations, picketing, the morning, noon, and night meetings, and singing, of course, always the singing across the street in Brown Chapel. I slept there for two weeks, except for when we all were arrested for picketing Mayor Smitherman’s home and spent the night on the floor of the Negro Community Center, and the night we bivouacked in a wet field outside of Montgomery, the fourth night before finally entering the city proper on March 25th.

I remember one afternoon sitting in the kitchen with Mr. and Mrs. Bell during their work-week lunch break. We shared toast sprinkled with sugar and cups of coffee while watching Governor Wallace yammering on a flickering black-and-white TV screen. I remember the room being very quiet except for a few of Mrs. Bell’s “Um. Um. Ummmms.” Mostly, my time was spent in and around Brown Chapel. We all were hopefully waiting for the word that would come down from federal district court allowing us to march to Montgomery.

♦ ♦ ♦

What didn’t I know? I didn’t know until much later that the road to Bloody Sunday, which ultimately lead to the Selma to Montgomery March, actually began two weeks before the Edmund Pettus Bridge assault. The original impetus was the cold-blooded murder of a young black man named Jimmie Lee Jackson in Marion, some 27 miles west of Selma. This occurred during a February 18th night demonstration for voting rights. James Orange had been arrested and there was talk of the Klan breaking into the jail to lynch him.

People were so enraged by the murder that they wanted to immediately march to Montgomery and lay Jackson’s coffin on the steps of the capitol. Discussions were held, and it was decided to hold off and to plan clear logistics for a march that would originate in Selma. Jimmy Lee Jackson was buried in Marion with Dr. King officiating. Two weeks later, 600 people, including many from Marion, were assembled and began the march across the Pettus Bridge and into the history books as Bloody Sunday.

I didn’t know before I went to Selma about Selma’s children’s crusade. I learned about that from Miss Annie Vickers. I also didn’t know much about the political and tactical tensions between the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). If you were white and had not been in the trenches of the Southern civil rights movement for a year or two, you had much to learn.

The Rev. James Reeb, Viola Liuzzo, and Jonathan Daniels, along with Jimmy Lee Jackson, were some of the many foot soldiers who perished during that period and now are footnoted in the history books. It’s worth the time of anyone reading this account to look up their names, especially considering the state of our country circa 2023, when our right to vote and the legitimacy of our elections is in peril. The names and examples of these foot soldiers cry out to be known. It is also why, after all these years, the face, words, gestures, and kindness of Miss Annie Vickers of Selma, Alabama, has never left me. But I am arriving too soon at the end of my story instead of setting the scene. I think again of words nosing their way around a dark room, the fragments of that time.

♦ ♦ ♦

When the ruling came finally legalizing the march and President Johnson federalized the Alabama guard, we marched out of Selma with Martin Luther King—around 2,000 strong—on March 21, 1965. According to the court order, only 300 people were allowed to continue through Lowndes County. The highway leading out of Selma was four lanes but it changed to two as you got into Lowndes, a notoriously dangerous section of road due to Klan activity. This meant that most people marching during the day were ferried back and/or forth from whatever point they were on Highway 80, either returning to Selma or going forward to Montgomery for the night. Volunteer cars or trucks would rest by the side of the road, and when you were tired or ready to leave the line, you’d catch a lift back or forward. A helicopter flew overhead and the Alabama National Guard stood at various checkpoints, either in clusters or at solitary positions.

Headline from Nicole d’Entremont’s report on the Selma March for the Catholic Worker, reprinted in the May 7, 1965, edition of the Ascent, with image of the south view of the Edmund Pettus Bridge (DXR/Wikimedia Commons)

It took two days to cross Lowndes County. On the fourth day even more people joined the line. At that point, all were allowed to camp that night in the field of the City of Saint Jude parish located in the outskirts of Montgomery. By the fifth day, the march had swelled to 25,000 strong.

Every day was filled with song, but I remember that day, especially, as one long cascading round of alternating song. Someone ahead of you might start singing, “Oh Freedom,” and at the last verse there would be a pause and another voice would rise out from somewhere, “Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me Round.” Clusters of black residents, unlike in the more rural, isolated parts of the county, came to the sidelines, waved, and cheered. As we got into Montgomery proper, there were other intonations—jeers from, especially, young white men, the ubiquitous finger. I remember a limp confederate flag hanging from a tall office building’s window. But nothing stopped the singing. It swelled, a great wave, higher and higher; then fell, drenching us in sound and jubilation.

By the time the throng assembled and the great mass stilled, Martin Luther King’s voice rang out, “How long? Not long!” and the cadence of his language took flight—the moral arc of the universe flinging long but bending towards freedom. “How long?”—and the roar of the crowd, “Not long!”—bearing us all into that dreamed-for future. Meanwhile, it was reported that Governor Wallace watched the proceedings high in his capitol office, peering through the slats of his venetian blinds.

♦ ♦ ♦

After the march was over, Sean and I were lucky enough to catch a farm truck filled with folks returning to Selma. It was a big, lumbering thing with wooden slats on the side and I remember standing up and waving and cheering to people on the sidewalks as we rode out of Montgomery. It was only as we crossed into Lowndes County that we were told to hush and women and children to scrooch down. I still remember the eyes of a small black boy beside me as our glances met. I’m sure I looked frightened too. By then, I had heard enough to be fearful.

We returned, of course, to Brown Chapel. People milled about. Sean and I found our patch of grass to sit upon and watch, listening to laughter, bits of conversation. A cluster of Alabama guardsmen were not far from us having their own recap of the past five days. Sean said he wanted to go over and talk to them. I didn’t think that was a good idea, but he got up and strolled over. I watched as he approached the group, the cluster of guardsmen stepping back, parting a bit and then encircling him. I kept watch and was relieved when a few minutes later the circle parted and Sean came back. I asked him what happened. He said they told him to get his Jew-boy ass back to New York, cause by 12 a.m. they aren’t federalized.

First there was a ripple, people huddling, talk, rumor, a change in emotional temperature, dusk approaching, more talk, someone crying, something had happened, Lowndes County, a car, off the road, shots, someone killed. This was how rumor, then fact, circulated around Brown Chapel, and how Sean and I learned that Viola Liuzzo had been shot and killed on Highway 80.

We didn’t return to New York right away. I don’t know if the murder of Viola Liuzzo was the biggest factor in that decision. We just hadn’t discussed that part of the trip. Sean had heard that someone (SCLC or SNCC) was organizing a clean-up around Selma for the next week since so many of us had been housed in the community, and we talked about doing that, but the next day nothing had been organized. In the absence of a plan, we decided to go for a walk. There were other parts of the community we hadn’t seen since Brown Chapel was so central to all activity.

That afternoon we took our walk, heading away from Brown Chapel. Frankly, even with the horrible news about Viola, it felt good to be out on a sunny, warm day without any kind of urgency or real purpose. The roads were dirt and narrow, a stray dog appearing now and then, clusters of small wooden houses and flowers . . . There was nowhere to really get to for any particular reason. It felt like a vacation until it didn’t.

And it didn’t because we both sensed about the same time, or heard or intuited, that we were being followed by a pickup truck close behind us. It sped up when we quickened our pace and slowed when we slowed. We both looked backwards to see white guys in the cab. At the same time, we were also being observed by a brown woman in her yard behind a fence where she was cutting flowers. She looked at us; she looked at the pickup; she motioned us with a wave to come into her yard. We did. The pickup lay on the gas, sped up, and spun off down the road. This is how we met Miss Annie Vickers, and along with her “Um, um, ums” and a shaking of her head, she ushered us into her little home.

Somehow I still keep hearing those “Um, um, ums,” and I can see her lean face and high cheekbones and hear her words: “Do y’all know how to get back to your church?” Back to “our” church? No, we didn’t. Did she draw us a map or just point the way? I can’t remember. We weren’t that far away. We just didn’t know. She said we should go directly but come back tomorrow the same time and she would make us lunch. She said her name was Miss Annie Vickers. We told her our names, thanked her, and left.

The next day we walked swiftly and purposefully to the home of Miss Vickers. I remember her little home, the one room, the quilt on the big bed, her friend the Deacon, who was also invited and who stood by Miss Vickers’s small cast-iron wood stove. He was wearing a crisp white shirt and black pants. Miss Vickers had cooked up a wonderful meal for Sean and for me on that little stove. She motioned us to sit on the big bedspread with the bright patchwork quilt as she served us each a plate of fried chicken, black-eyed peas, rice, and collard greens. I think there was cornbread, too, and a peach cobbler and chicory coffee for dessert. This remains, still, one of the most memorable and delicious meals I have ever eaten in my life. As I recall, for the previous two weeks, Sean and I had mostly lived on donated baloney sandwiches and Tropicana orange juice in little cartons. We sat on that bed and ate everything, and I am sure we had seconds.

That was 58 years ago. I see them both: the Deacon’s skin, coal black, black with a kind of shine, and Miss Annie Vickers’s a reddish shade of brown with those high cheekbones. No cameras then, but it wouldn’t have caught the lively eyes, the glint of conversation or the sound of rain on the tin roof.

It was from Annie Vickers that I learned about the kids in Selma, how they had demonstrated in February, had been beaten and driven on a forced march out of town by Sheriff Jim Clark and his posse of men armed with clubs and cattle prods. How they were jailed in Camp Selma. Another footnoted event in the history books. She looked at us . . . “Oh, you chillin’—you chillin’ are answering the Macedonian Call.” I had no idea what she meant then as I sat on her bed, listening to the rain, but it seemed huge and right, sitting there, safe for now. “Oh, but you chillin’ are rockin’ the boat. Aren’t they, now, Deacon? Aren’t they rockin’ the boat?” Sitting on that bed, then, I wasn’t sure.

Many years later, I was to learn that the “Macedonian Call” had to do with answering a plea from a people urging others to come and help them in their hour of need. I wish I could talk to Miss Annie Vickers today, now that I am 80 years old. I wish I could tell her how her words and actions that day still rock my boat. How grateful I was that she saw and acted so swiftly when she ushered Sean and I into the safety of her home and later fed us with food and with stories. Her actions remain for me the singular great teacher if one is to answer the Macedonian Call. ♦

Nicole d’Entremont lives on an island in Maine and thinks one way to build a bridge between Peaks Island, Maine, and Selma, Alabama, is to support the Foot Soliders Park and Education Center.

These are the stories that need to be heard.