“The Hallowing of the Real”: Small Christian Communities and the Universal Priesthood

Last year, Today’s American Catholic convened a listening session in response to the “Synod on Synodality.” A key point of our discernment was that people are longing for a deeper sense of community in their experience of faith. We discussed small Christian communities (SCCs) as a promising way to foster relationships and help participants be more proactive in learning about and living the gospel.

Encouraged by this discernment, TAC started a pilot program to host, promote, and network new and existing SCCs. This essay is the second in a planned series on the practices, theology, and spirituality of SCCs; the first, “Cords of Human Kindness: An Introduction to Small Christian Communities,” is available here—Ed.

Regardless of the outcome of the universal stage of the synod this October, the documents we have already assembled at the local and continental levels will remain, creating a legacy, or a repository, of what the people of God were living, thinking, feeling, reimagining, and renewing at a particular moment in the church’s history. One item that comes up repeatedly in reviewing these documents is that of “common baptismal dignity,” “the basis,” in the words of the Episcopal Conference of Mexico cited in the Continental Document, “of co-responsibility in mission.” The U.S. “Region XVI” Synthesis adds a sacerdotal shading to this theme when it includes as one of its recommendations a “return to the spirit of Vatican Council II, [to] robustly affirm by word and action the sensus fidelium, the communion of saints, and the priesthood of the baptized.” This language links directly to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

The baptized have become “living stones” to be “built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood” (1 Pet 2:5). By Baptism they share in the priesthood of Christ, in his prophetic and royal mission. They are “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, that [they] may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called [them] out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Pet 2:9). Baptism gives a share in the common priesthood of all believers. (§1268)

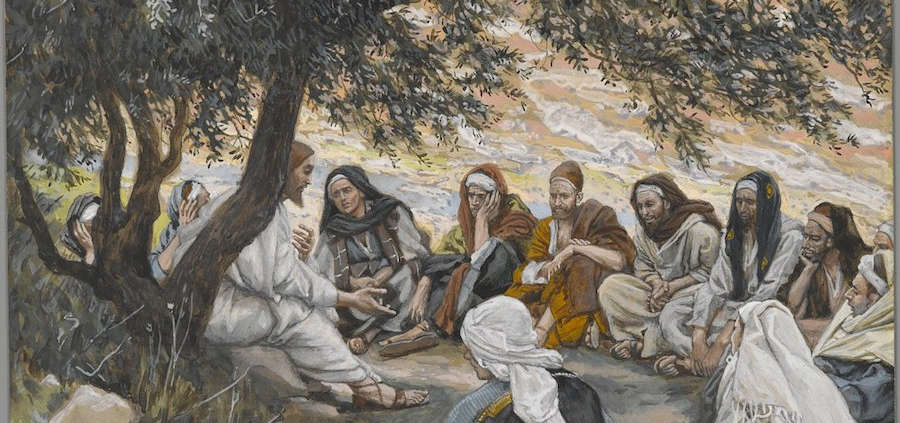

One of the primary gifts of the small Christian community (SCC) is that it helps participants to recall, honor, and reify this baptismal promise and its priestly function at every gathering. This gift is foregrounded by the fact that there may be no ordained member of the SCC, and so participants must model their “common priesthood” for each other. They do this, first, by a kind of ministerial listening in which they “hold space” for one another as they unspool and unpack the week’s lectionary readings; they reflect back to each other their insights, struggles, points of inspiration or friction with the texts, and elaborate upon these reflections out of the storerooms of their own experience. In the same way the synodal listening sessions became a form of collaborative discernment—a movement from intellectual solitude to a vision cowritten, as it were, out of a multiplicity of voices—the SCC gathering is an opportunity for each person to become responsible to all, exercising their priestly capacity to shape shared moments of illumination.

Such a close alignment of laypeople to the role of the priest may seem to some presumptuous, or doctrinally unsound, or simply a case of “magical thinking.” Part of this resistance comes from the way in which we perceive the priesthood in the Catholic Church, having, in many places, diluted its mythic, poetic, and panentheistic significance in favor of a drab functionalism: the priest as administrator of a branch of the church as corporation, cooped up indoors, secretly if not openly skeptical of its ability, and its duty, to divinize the world. Paula Huston draws on the work of theologian (and key contributor to Vatican II) Henri de Lubac to underscore this very point. De Lubac, she writes,

devoted much of his thinking to what he saw as a major problem in contemporary Christianity: the strict separation between nature and the supernatural that was introduced by the scholasticism of the late Middle Ages. He pointed out that, before Thomas Aquinas arrived on the scene, Christians had lived in an undivided universe. There was no such thing as a purely physical world standing dumbly on its own. And likewise, no such thing as a separate supernatural order of reality that occasionally penetrated the mundane in order to carry out some mysterious project on God’s behalf.

Instead, the old understanding of the “supernatural” was sacramental: it referred to the “sacramental means of grace that allowed nature to reach its divinely appointed end: eternal participation in the divine life itself (deification).”

The future of our planet—God’s gift to us, the very “theater” of our salvation—depends on our ability to restitch the divisions of this post-scholastic worldview. We do this most summarily in our celebration of the Eucharist, when the link between the “natural” symbol of the bread and wine and the “supernatural” sacrament of Christ and his kingdom come together in a moment confected by the Holy Spirit. And yet, as Fr. Alexander Schmemann articulates in his book For the Life of the World, everything is a sign of the sacred because it has been created by God. This means that the relationship between the world as sign and symbol and the world as sacrament is not limited to the Eucharist alone; it extends to all of nature, to the rivers and trees and stones, which can then be “lifted up” to God with the same joyful hymn of praise. This is the work of consecratio mundi, the “consecration of the world,” and it is why Fr. Schmemann (with concessions to his gendered language) can remind us that

[t]he first, the basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands in the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God—and by filling the world with this eucharist, he transforms his life, the one that he receives from the world, into life in God, into communion with Him. The world was created as the “matter,” the material of one all-embracing eucharist, and man was created as the priest of this cosmic sacrament.

“Eucharist,” we are right to remember here, means “thanksgiving,” and SCC participants are in a prime position to practice living eucharistically. For one, the SCC is democratized by age and social status and declericalized by rank; it is already a sign of the nonhierarchical kingdom, making it easier for participants to cultivate and contribute their priestly gifts without fear they are overstepping the bounds of their lay apostolate. Some of this fear may be rooted in the fact that in the Catholic liturgy, greater emphasis is placed on the priest’s words of institution (“This is my body . . .”) than the epiclesis which precedes them (“Make holy, therefore, these gifts . . .”) and is directed to the Holy Spirit. This has the subtle if unintended effect of tethering the Eucharistic mystery—what Catholics understand as transubstantiation—to the actions of a single person. As vital as those actions may be, a repeated referral of the Eucharistic mystery back to one member of the assembled congregation may weaken our ability to experience the Holy Spirit collectively and perceive how that Spirit is moving us into deeper union, both inside and outside the church; it may also limit the full range of meanings of eucharist as presented by Fr. Schmemann in the passage above, preventing us from recognizing its “all-embracing,” “cosmic” quality and our attendant duty to name, bless, and bring the world into communion with God.

None of this should be taken to mean that the SCC is a substitute for the Eucharistic celebration. Far from it—the Christian liturgy, as Paul Evdokimov once wrote, is “the irruption of the heavenly into history,” and the Catechism’s characterization of the Eucharist as the “source and summit of all Christian life” stands unabated. What the SCC can provide, however, is a forum for participants to habituate themselves to living, thinking, and acting eucharistically. The SCC is not simply a faith-sharing group; as a kind of “parish within a parish” or “community within a community,” it retains within its organizational structure and communal dimension a living connection to the church. This sense of “ecclesial memory” informs the activities of the SCC, so that even in the absence of a Eucharistic celebration, the gathering remains a fertile space for the deepening of a eucharistic consciousness. Participants embark on this process by making offerings of their time, their texts, and, above all, themselves. Their period of reading aloud from the Scriptures corresponds to the liturgy of the Word in the Mass, while the period of prayer, sacred sharing, and collective discernment that follows is an occasion to exercise their priestly gifts with one another and thus has resonances with the liturgy of the Eucharist. At its highest form, each person feels a responsibility for the spiritual striving of all, and they place themselves before each other in mutual self-gift that emulates the “giftedness” of Christ in the sacrament.

In the collection of Carthusian novice conferences Interior Prayer, a young monk, identified only as “Matthew,” is asked the question of what prayer is for him on the level of concrete experience. Describing it as “a current, and a state of awareness,” he says: “I think it is giving back to God what I receive. For example, I look at a tree, and I offer it to him.” This is what the Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel called “the hallowing of the real,” and our participation in this hallowing as devotional beings fulfills the words of Fr. Schmemann: “If the church is in Christ, its initial act is always this act of thanksgiving, of returning the world to God.” ♦

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic

I belong to 2 faith sharing groups.One is a Benedictine Prayer group.In this group we reflect on the psalms and explore their meaning in our daily lives.I have been in this group over 10 yrs.

The other is a Catholic womens reading group.I have belonged to this group about 5 years They have both been instrumental in my life and pursuit of love and Christ in my daily life.I feel a great need to expand myself beyond reading and discussion into greater daily action.Can your group help with this?

Yes.