At Glendalough by Richard Lehan

Last fall I was back in Ireland after 24 years, this time with my wife. We spent three days in Dublin exploring old haunts from an even earlier period in my life as a graduate student at University College Dublin in the early 1980s. Now our rented, red Opel was headed for the Monastic City at Glendalough in County Wicklow. Navigating through morning rush-hour traffic in Dublin was a baptism of fire. While the pressure eased once we reached the highway heading south, it ramped up again as we traversed the unforgiving, hedgerow lanes of the Wicklow countryside. I discovered that driving on the “wrong” side of the road after so many years is not an exercise in muscle memory; it called for a bracing dose of unbroken concentration. Even so, we made it to Glendalough in one piece in less than two hours.

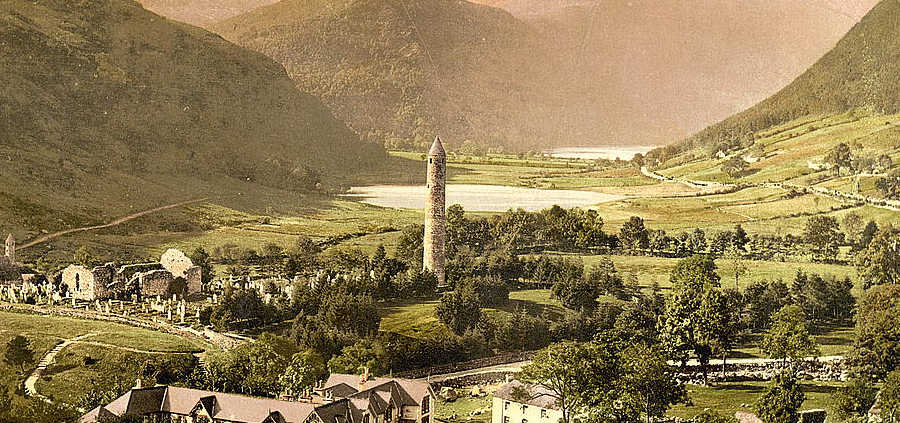

Glendalough, meaning “valley of two lakes,” was carved into existence by a glacier during the last ice age. Over time, the Poulanass River split the original lake in two. The resulting Lower and Upper Lakes are nestled in the Wicklow Mountains, today part of an expansive national park.

St. Kevin established a monastic settlement in the lower valley of Glendalough in the sixth century. According to the visitor’s guide, Kevin was a descendant of one of the ruling families of the historic Irish province of Leinster. As a boy, he studied under the care of three holy men and lived “in the hollow of a tree” at Glendalough. Years later, Kevin returned with a small group of monks to establish a monastery. As his fame as a holy man spread, numerous followers joined him at Glendalough. One day as Kevin prayed in his cell, his hand held heavenward through the cell window, a blackbird came and laid her eggs in his palm. As Seamus Heaney recounts the legend in his poem “St. Kevin and the Blackbird”:

Kevin feels the warm eggs, the small breast, the tucked

Neat head and claws and, finding himself linked

Into a network of eternal life,Is moved to pity: now he must hold his hand

Like a branch out in the sun and rain for weeks

Until the young are hatched and fledged and flown.

Glendalough flourished for another six centuries before it was reduced to ruins by English forces in 1398, though it remained a place of pilgrimage. The buildings and monuments on site today date between the 10th and 13th centuries. In its heyday, the Monastic City included not only a round tower, cathedral, and several other churches, but also areas for manuscript writing and copying, workshops, an infirmary, farm buildings, and dwellings for both the monks and a large lay population.

My wife and I entered the Monastic City by foot through the Gateway, one of Glendalough’s most unique monuments. Originally two stories high, the Gateway’s double granite arches are its defining feature. A cross-inscribed stone in the Gateway’s western wall denoted the boundary of the monastery’s sanctuary. Once inside, the path curved up and to the right where the 98-foot-high Round Tower came into full view. Built of mica-slate and granite, the tower’s interior historically had six timber floors connected by ladders and is topped with a conical roof. The Round Tower served several purposes: as a landmark for approaching visitors; a storehouse, if needed; and place of refuge in time of attack.

The gravel path connecting the monastic complex brought us to the cathedral, the largest building in Glendalough. Now roofless, it was constructed in phases with its chancel and sacristy dating from the late 12th and early 13th centuries. About 10 feet away stands St. Kevin’s Cross, made from local granite; it may have marked the boundary of Glendalough’s cemetery. Close by is the Priests’ House, where the bodies of priests were interned in the 18th and 19th centuries, though it was originally thought to have stored relics of St. Kevin. At the bottom of the slope off the cemetery is St. Kevin’s Church, a mica-stone building with a steeply pitched roof and a belfry that resembles a miniature round tower. It was commonly known as “St. Kevin’s Kitchen” because people believed that the bell tower was a chimney to a kitchen, but no food was ever cooked there.

There was a modest crowd of visitors at Glendalough on that day in late September. Most appeared to be older, foreign travelers like the two of us, poking through the ruins and posing for photos while the Monastic City maintained its dignified silence. As we turned back toward the cemetery, a deer darted suddenly between the gravestones while camera phones snapped away. In the background shimmered the two loughs of the valley, our next destination.

Pathway in County Wicklow, Glendalough. Oliver Gargan / Wikimedia Commons

The route to the lakes is via a nearby wooden bridge over the Glendassan River to a packed dirt way called Green Road. As we walked along, two deer climbed across the steep slope of oak trees on our left while the river flowed below us into the Lower Lake, pooled serenely at the base of the valley. More monastic ruins are dotted around the larger Upper Lake at the end of Green Road. Reefert Church, dating from around 1100, sits in a grove of trees near the Poulanass River and waterfall. With the legend of St. Kevin and the Blackbird in mind, we went looking for St. Kevin’s cell. Built on a rocky spur overlooking the Upper Lake, the cell may have had a stone-corbelled roof similar to the “beehive” huts on Skellig Michael off the coast of County Kerry. One of the maintenance crew working on a trail pointed us in the right direction. When we found the spot, two couples were picnicking on top of its remaining flat stone slabs.

At ground level, the glassy waters of the Upper Lake widened out between the valley slopes. Somewhere along the southern shore of the lake, accessible only by boat, is another small church, Temple-na-Skellig, and not far from it, St. Kevin’s Bed, a cave reputedly used by him as a retreat. Neither one was visible to us, but their hidden presence added to the mystique of the setting. We stood on the small, sandy shore of the Upper Lake contemplating the postcard-like vista for a few minutes. The arc of time streams through this valley; its breadth and porous boundary between past, present, and future enveloped us in a humbling temporal awareness. In the field opposite the lake lies the Caher, a circular stone enclosure about 65 feet in diameter, its date of origin unknown. Nearby are several stone crosses that possibly marked the route of pilgrims.

We had come to the end of our own pilgrimage to Glendalough; it was time to turn back toward the Monastic City. After staying the night in the town of Wicklow, our sojourn continued south to Kinsale on the coast of County Cork.

♦ ♦ ♦

Back home, I thought more about why the experience of being at Glendalough resonated with me so much. Heaney’s poem closes with a revelation of the “fruits” of Kevin’s monastic vocation:

Alone and mirrored clear in love’s deep river,

‘To labour and not to seek reward,’ he prays,

A prayer his body makes entirely

For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river’s name.

In solitude, Kevin’s mirror-clear immersion “in love’s deep river” enabled him to act with a purity of heart that transformed his very body into a prayer offering. Through the refining fire of self-forgetfulness, Kevin emptied himself out for service to others. As a contemplative, the one necessary discipline was to root himself in God’s presence; Kevin’s compassion and selfless service arose from that prayerful ground.

Kevin, the founder and abbot of a nascent monastic settlement, also set in motion the evolution of Glendalough into a vibrant “city” of monks and laypeople. That history tells me that Glendalough was not about sealing the consecrated off from the outside “fallen” world. Instead, Glendalough offered others hospitality, refuge, and the opportunity to share in its faith-based vision of the good life. Its mission was not only about modeling by way of example, but also actively engaging with the wider community to promote the flourishing of all.

Finally, from the boy living in the hollow of a tree to the saint making his palm a nest for a blackbird in need, Kevin embodied the Celtic Christian ethos that saw the natural world as saturated with the divine presence and humans “linked into a network of eternal life” with the rest of nonhuman creation. Tucked in a woodland valley of rivers and glacial lakes, Glendalough was a community embedded in a hallowed place. Its verdant setting fostered a sense of reverence and restraint that sought harmony with, not domination over, nature. When one’s vision of reality is sacramental, exploitation gives way to stewardship.

Far more than a museum of “ruins,” Glendalough witnesses to a way of being and living in community that “sings” like a hymn through time. May receptive ears hear its music! ♦

Richard Lehan is a writer living in Massachusetts. His essay “Contemplative First, Writer Second” appeared in Today’s American Catholic in August 2022.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!