Seizing the Sacred in the Faith of Others by Patrick Henry

The 1960s were not only the time of the civil rights movement and protests against the war in Vietnam. They also witnessed one of the greatest interfaith movements in our history. In the wake of the Holocaust, Christian churches were confronted not only with their failure to act on behalf of the Jews during the genocide itself, but, more centrally, they faced the fact that their anti-Judaism, antisemitism, and teaching of contempt for the Jews from the fourth century onward actually made the Holocaust possible.

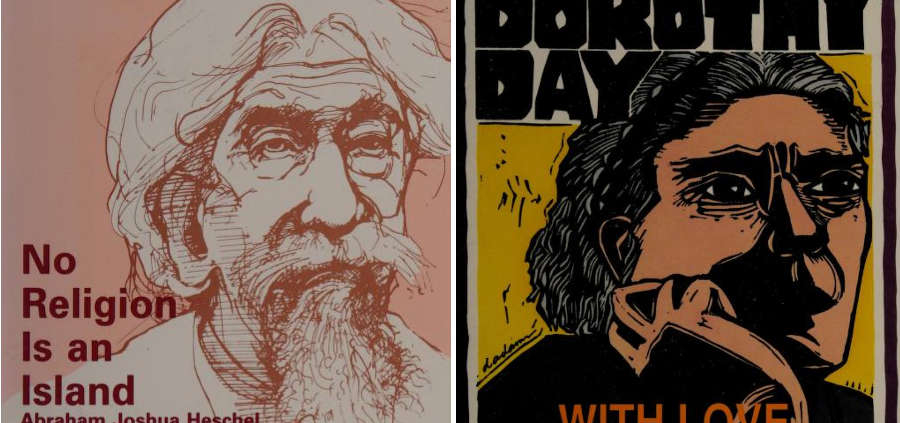

Most Christian churches offered formal apologies to the Jews and redefined their relationships to Judaism and the Jewish people. Historical footage depicts the coming together of clergy from all religions at antiwar protests and in civil rights marches. What strikes me most, however, as regards the potential for interfaith understanding, tolerance, and peace among communities of different religions, are examples of deeply religious individuals who recognized the sacred in the religion of others. Let me cite but two examples.

♦ ♦ ♦

Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker and lifetime social worker among the poor, graduated from high school at the age of 16 and immediately began her studies at the University of Illinois in the fall of 1914. During her second semester, she applied for admission to a writers’ club, the Scribblers, and was interviewed by Rayna Simons and her boyfriend, Samson Raphaelson. They immediately accepted her into the club. Rayna “stood out like a flame with her red hair, brown eyes, and vivid face,” writes Day. She looked “honest and sincere,” and was beautiful, wealthy, joyous, and brilliant. But all this was not quite enough to get her an invitation to join a sorority. Why? Because she was Jewish. “It was the first time I came up against antisemitism,” Day tells us. Rayna would become her best friend. Day spent her second and last year of college living with Rayna in a boarding house for young Jewish women close to the university.

This initial contact with antisemitism marked Day deeply. She would spend years fighting antisemitism inside and outside the Catholic Church. During the war years, for example, years marked by papal silence regarding the plight of the Jews, she drew attention to the persecution of the Jews throughout Europe and called for nations to open their borders to them in articles for her newspaper, the Catholic Worker.

Her posthumously published diaries, collected as The Duty of Delight, depict her as an avid reader of Jewish literature, fascinated by “the deep spirituality of Orthodox Jews [and] their devotion to Scripture, the Talmud, [and] the Sabbath.” In her first autobiography, From Union Square to Rome, published in 1938, she describes the room she rented and tells her readers about the Gottlieb family and their four children with whom she lived for a year on Cherry Street in lower Manhattan. They lived in deep poverty, “no electricity, no bath, no hot water, no central heating. [They used] public showers around the corner.” But Mrs. Gottlieb was an excellent housekeeper and cook who knew Day had little money and “left a plate of soup or fish for [her] at midnight so that [she] fared very well.”

In her diaries, 55 years removed from “that little room” in the tenement, Day dramatically explains the tremendous impact that this Orthodox family had on her sense of the sacred and her conversion to Christianity. “I knew nothing of Jews,” she writes in April 1972, “until I lived with a Jewish family on the lower East Side when I was eighteen.” She then relates that when the meal was left for her by Mrs. Gottlieb, there was often a note written in English by one of the children (“the parents knew only Yiddish”) explaining “no milk or butter, if I had meat.” This “ritual about food gave me a sense of the sacramental,” she explains; “living there brought my conversion to Catholicism closer.” Finally, she remarks, “I began to know the Jewish people then in the breaking of bread, as I was later to know Christ.”

Dorothy Day had an absolute reverence for Judaism and always considered Christianity umbilically linked to it. She read the Psalms dutifully every morning of her post-conversion life and recognized that salvation for Christians came from the Jews. She notes in her diaries in October 1978: “[The Jews] are indeed God’s chosen. He does not change.” For her, “All Christians are converts to the God of Israel who is the true God.” Finally, influenced by St. Paul’s Epistles to the Corinthians and the Romans, she stresses often in her writings that we are all members of the same body. As Pope Pius XI said, and Dorothy was fond of repeating, “Spiritually we are all Semites.” Antisemitism, therefore, constitutes a serious violation of Christian doctrine, a wound inflicted on the body of which we are all members.

♦ ♦ ♦

Perhaps the most important interfaith activist during the 1960s was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Born in Warsaw, Heschel managed to get to London six weeks before the Germans invaded Poland. He arrived in the United States in March 1940. Most of his family was murdered in the Holocaust. He was a professor of Jewish mysticism at Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York City.

No one formulated the preconditions necessary for successful interfaith dialogue better than Heschel. And he did so in brilliant, stunning, and original aphorisms. Listen to him:

- God is greater than religion.

- Faith is deeper than dogma.

- Religion is a means, not an end.

- To equate religion and God is idolatry.

- Religious pluralism is the will of God.

- No religion is an island. We are all involved with one another.

- People of faith must open themselves to others at the level of faith.

- Holiness is not the monopoly of any particular religion or tradition.

- Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are part of God’s design for the redemption of all human beings.

- God is either the God of all people or of no people.

Heschel practiced what he preached. Strikingly, in his March 1966 “Interview at Notre Dame,” he remarked: “Jews, in their own way, should acknowledge the role of Christianity in God’s plan for the redemption of all people . . . I recognize in Christianity the presence of holiness. I see it. I sense it. I feel it. You are not an embarrassment to us and we shouldn’t be an embarrassment to you.”

He went to Rome and convinced Pope Paul VI not to include anything about the need to convert Jews in Nostra aetate, the official Vatican II document on the church’s relationship with non-Christian religions. Two months before he died, again in Rome, he spoke for the only time at an interfaith conference that included Muslims. Heschel spoke in favor of dialogue, stressed the specific continuity between Islam and Judaism, and proclaimed that “The God of Israel is also the God of Syria and the God of Egypt.”

Working together with Christians, teaching at Union Theological Seminary with Protestant and Catholic students in his classes, Heschel created new, exciting possibilities for insights and learning. He was the first Jew to receive an honorary degree from a Catholic University, and the first to hold the Fosdick Visiting Professorship at Union Theological Seminary. His impact in Christian circles was so great that he was often referred to as a “shailliat la-goyim,” an “apostle to the Gentiles.” Eva Fleischner and others believed that Heschel “may have done more to inspire an enhanced appreciation of Judaism among non-Jews than any other Jew in post-biblical times.” ♦

Patrick Henry is Cushing Eells Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Literature at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!