Eternity Is Made of Days: The Poetic Lives of Ann Manganaro SL by Michael Centore

Give Me a Living Love

By Ann Manganaro SL

Sisters of Loretto, 2023

$15 54 pp.

I

The first thing one notices when scanning the contents of Give Me a Living Love: The Poems of Ann Manganaro SL (1946–1993) is how many of the entries are titled by date. Some include dedications or geographical locations (“For Peter: 29 January 1989”; “La Palma: 14 September 1992”); others are identified by season (“Late winter, early spring, 1978”); several come in with the precision of month/day/year or month/year format (“9/16/77”; “12/77”). The effect is that of a collection—like Robert Creeley’s Hello: A Journal, February 29–May 3, 1976 or Robert Lowell’s Notebook 1967–68 or Philippe Jaccottet’s Seedtime with its hybridizations of prose and verse—whose structure is its chronology: the movement of time is itself the cumulative theme of the poems, something the reader detects in parsing the dates like mile markers, one after another, the horology of a life lived twice—first as experience, then as writing.

These three days of February

Flower upon me suddenly,

Crowding my still unsteady earth. (“2/20/77”)

Nathan Kernan has observed that a typical poem by James Schuyler “seems to have been written at one sitting; the day itself is the subject . . . of the poem.” He writes: “Schuyler’s poems often draw our attention to the idea of Day as the infinitely varied yet unchanging, inexorable unit of passing time: ‘The day lives in us and in exchange / We it’”. Manganaro and Schuyler are very different poets, with different preoccupations, but they share that sense of “exchange” (the lines Kernan quotes are from Schuyler’s “Hymn to Life”) between the shape of a life and the day—and the poem of the day—that contains it. Creeley articulates this space in the opening lines of “Again”—

One more day gone,

done, found in

the form of days

—as does Cid Corman, in his characterization of Jaccottet’s work as “intimate and open, a soft cry at moments of given days,” and Zbigniew Herbert in his paean to the “holy ritual of everydayness” without which “time is empty like a falsified inventory that corresponds to no real objects.” There is Lowell, too, who wrote of his aforementioned Notebook: “My plot rolls with the seasons.” Manganaro gathers up these aperçus and re-presents them in “3/5/77,” a poem ostensibly about a train journey but really about those moments of transition—life’s liminal spaces, “Not winter, not yet spring”—that turn time like the hands of a potter to define a vessel of days. Here are the final eight lines:

I ride the season’s wild subliminal color,

Deep orange, dark red hills and grasslands, the trees

Indigo flashes against the glass, vivid hues

Which simmer at my eyes’ edge unfocused,

To succumb finally under the iron wheels.Without even a flicker of green

Spring stalks winter across these hills:

The still space silently fills.

The “still space” of the final line holds the transitional moment between seasons; in that stillness, that emptying of winter into spring, we grasp a central paradox of nature: that its inward processes of growth and change and decay and rebirth, no matter how dramatic, all happen in total silence. Likewise the processes of the imagination that are embedded in the poem—the “still space” could be that of the creative mind as it perceives the “wild subliminal color” of seasons still hidden in the landscape, or of the blank page onto which these perceptions are configured. Nature and imagination, in a way, become here metaphors for one another, unified in their mutually revelatory power: “Spring stalks winter” as the imagination stalks the image, the kairotic moment of poetic composition; the imagination collects, winnows, sifts, “composts” its perceptions to reflect and renew on the verbal level a landscape that is undergoing a similar process on the physical. Each one speaks to the other in silence across a slow “simmering” at the edge of the eyes—another borderline, the boundary between the seen and the unseen—to conjure together the dream of an emergent spring. One thinks here again of Herbert: “Eternal greenness speaks to the imagination better than eternal light”—or of the Iranian poet Sohrab Sepehri’s “The Token,” with its image of a “wooden lane / Greener than the dreams of God.”

The silent dialogue between nature and the imagination evoked in “3/5/77” is rendered with a rich interior music. As we move down through its final eight lines, a series of harmonic echoes give the poem a shape and structure, creating almost a “vessel” in sound:

ride wild

flashes glass

unfocused succumb

By the time we reach the last two lines, the triple rhyme of “hills”/”still”/”fills” tightens into a kind of sonic base. The correspondences of the three words interlock into a foundation of rhyme, with rhyme’s locked-box feeling of closure. Our ear assigns a “bottom” to the harmonic structure, that vessel or container carrying the privileged poetic moment. The “still space” might be the very center of this vessel, the silent, stationary point from which we observe the flux of the world, much like the speaker who sits motionless on a moving train, observing the passing landscape.

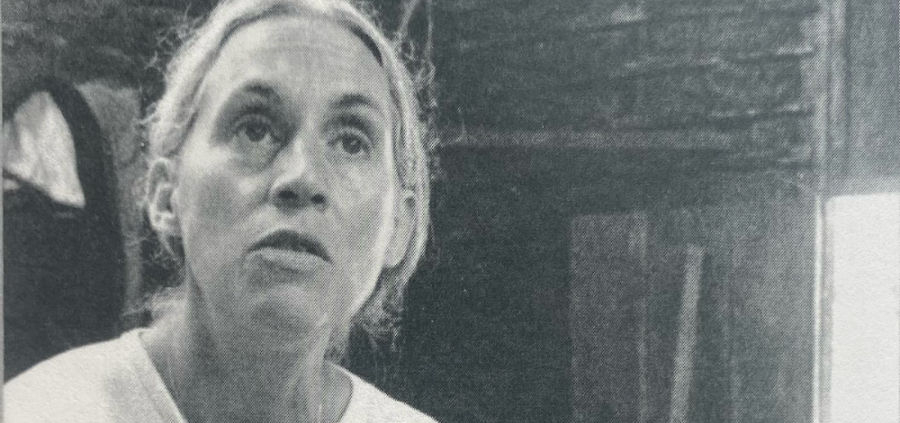

I say “the speaker” out of a sense of literary propriety, but in truth the voice animating all of these poems is Manganaro’s. She is a writer whose work rewards biographical criticism, partially because of its diaristic tone and partially because of the neat cleft, pointed out by Kathleen DeSutter Jordan in her loving and insightful introduction, between two distinct periods of her creative life: a period of personal lyrics written in her thirties, and a second period of more politically engaged work written while volunteering with the Jesuit Refugee Service in El Salvador in her forties. Taken together, the two periods turn on a common hinge of love: a love for her native St. Louis community, where she discerned her vocation to the Sisters of Loretto, taught at local elementary schools, and cofounded a Catholic Worker house; and a love for the people of El Salvador whom she served as a physician at the height of that country’s brutal civil war. When she writes in another early poem that “The best of me was born in reciprocity”, we understand it in a way she couldn’t at the time of its composition, as both a reference to the reciprocal nature of love and the reciprocity between these two periods of her poetic output.

The love memorialized in the first period of poems grew out of her experiences of religious life and Karen House, the Catholic Worker community she helped establish, but found its most focused expression in her relationship with the Jesuit priest John Kavanaugh. Their love was deep, mutual, and chaste—“a most uncommon and difficult grace,” as Kavanaugh once described it. Two of the poems of this period are explicitly titled “For John,” and even those that aren’t bear traces of his presence:

But what

Will come, whatever I endure will now

Be hallowed by the elusive mystery of your love

Some strand of your life is now irrevocably woven

Into mine. (“12/77”)

The temptation when reading a poet with religious commitments like Manganaro’s is to let the object of devotion in lines like these mutate from the particular to the divine—to hear, in other words, every love poem as a love poem to God. Manganaro lends some credence to this view when she incorporates celestial imagery and images of flight into her lyrics. There is a recurring sense of the love experience as a taking-leave of the earth and its limitations:

Flying low, you float

Across a landscape of fallen stars

The city’s jewels, strung, stretched

Flung before you. (“2/28/77”)In the dream

My house was small and dark

So you called me out to visit your own.

But when you took my hand

We soared up among endless dawnless stars (“6/2/77”)

At the same time there the interpenetration of world and afterworld, life and afterlife, as if in realization of the request that concludes the poem “3/15/77”: “I’d have that heaven harried earthward oftener.” We hear this most explicitly in “5/77,” a litany or hymn to the natural world that begins with the immortal line “Praised be the sweet green smell of the stars in May”, moves through a celebration of cool air and crickets’ sounds and “the deep black sea of the spring sky”, and ends with two lines that erase the division between telluric and cosmic: “Praised be forever this fleeting night / Which lures the universe to enter into earth’s delight.” Creation is englobed in God, and eternity is made of days.

II

Carl Jung once wrote that “We meet our destiny on the road we take to avoid it.” In a poem dated March 14, 1979, Manganaro seems to have reached the crossroads of this avoidance and the subsequent encounter with her destiny. It begins:

A toast to the beautiful brown-eyed children we might

Have had. May their bright, impossible lives preside

Over all the days of our going separate ways.

Anyone who has seriously considered consecrated religious life will recognize the theme: it is a lament, addressed to Kavanaugh, for the relationship they will have to forsake for a wholehearted fidelity to God. There is a paradox here that I am sure Manganaro, in her deep love for humanity, surely recognized: that fidelity to God only comes through relationships, and that she and Kavanaugh were merely choosing to open themselves out to the wider human family instead of creating their own. These two choices are not mutually exclusive, and the fact that she is even elegizing the “impossible lives” that might “preside” over the next stages of their respective journeys hints at the ambivalence she must have felt in selecting one over the other. It also shows an understanding that “the other life”—the life lived as pure possibility that, as the poet Andrea Hollander writes in her poem of the same name, “you invent and invent / because it invents you back”—is itself as much a determinant of the course of our active, embodied lives as any other. Manganaro expresses this in the lines that first reminded me of Jung:

But the lives we lose illumine the path we choose

Which remains one within, however far

We part upon it.

With biographical symmetry befitting a poet whose life and work were so closely intertwined, we have the record of a second turning point precisely five years to the day after the first. “14 March 1984”—even the way the format of the date flips the title of “March 14, 1979” suggests a mirroring of the earlier work—is a kind of threshold poem, a stepping-through into the life left standing after all the alternate possibilities have fallen away:

Seek first the reign of God, the realm of God,

The place where God resides, where God abides;

In the open places or in the field hidden . . .

The language is explicitly theistic in a way that the earlier cycle of poems is not; the word “God” appears seven times in fourteen lines, and the quasi-archaic syntax and self-admonitory tone recall an earlier era of religious poetry:

The fruitful tree seeded in you, seek first:

That space, that place, that realm, the soil of God,

The holy ground within, wherein is come

Your God to dwell. Let this life in you burst

Open, let yourself become the very food

Of the feast you seek. Seek first the reign of God.

Nineteen seventy-nine was the year that Manganaro entered medical school at St. Louis University, motivated by what DeSutter Jordan identifies as a deepening understanding of her vocation. She had “a sense of mission to serve in an underdeveloped country,” and was willing, essentially, to begin her life again to make this happen; the 1984 poem thus represents the crest of her calling before a diagnosis of breast cancer in 1985 sidelined her plans and delayed the completion of a pediatric residency for an additional two years. There are no poems extant from this time. In January of 1988, she finally arrived to El Salvador as a volunteer with the Jesuit Refugee Service, and was assigned to the resettlement village of Guarjila in the Chalatenango province to serve as a physician.

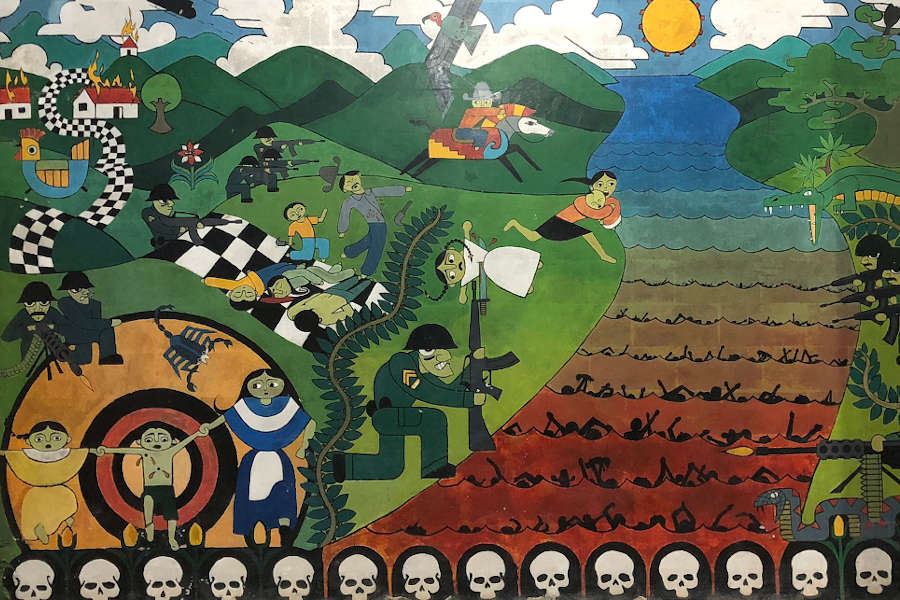

As a stronghold of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the guerilla movement that had risen up against the elite landholding class, Chalatenango had suffered considerable violence since the outbreak of the war. Most notorious was the Sumpul River massacre in May of 1980, when raids by the US-backed Salvadoran military forced hundreds of peasants to flee from their homes; after trying to escape into neighboring Honduras and being denied entry, the refugees were caught between the military and the rain-swollen river, where they were either killed or drowned. One particularly gruesome image that has endured is that of government troops tossing infants into the air and impaling them with bayonets.

Although such ruthless death-squad activity remained a threat—one United Nations study later found that 85 percent of the war’s atrocities were committed by state-sponsored troops—by the time of Manganaro’s arrival, Douglas V. Porpora reports, “it was largely replaced by saturation bombing in the countryside.” This was part of an overall counterinsurgency strategy to “drain the sea”—that is, to “dry up” the FMLN by targeting its bases of civilian support. In addition to rampant death and destruction, the bombing caused widespread displacement of persons: one million in all, or just under a fifth of El Salvador’s total population, would be uprooted from their homes before the end of the war. Half a million sought asylum in the US, but the government only approved a scant 2 percent of applications. Refugee resettlement villages such as the one Manganaro helped staff became a last resort for many.

Mural of the Sumpul River massacre, Chalatenango, El Salvador

Given these circumstances, it is remarkable that the Salvadoran sequence of poems is not more despairing. Hope is the recurring theme, as fire the recurring image: it blazes across all of these poems, sometimes destructively, as “pure fire illuminating the far / Horizon pitted against a smoky turbulence / Which stings the eye and heart”, or fatally, as in “End of November 1988”:

And what fire will burn

Away her pain, as the war-fire eats

Alive her son, sister, lover? Long

Years of this life’s death endured have worn

Her slender hopes to the bone.

Just as often, however, it is a symbol of incensive power and illumination, that “pure burning yearning / Aflame in face and limb and voice and eyes” that we might associate with the mystic or the prophet. In “For Peter: 29 January 1989”, Manganaro writes of the dedicatee’s “fiery eloquence” that “strikes / Like a hammer our hearts”, and ends with a plea for his steadfast spirit to rise “Across the dark / Horizon rife with evil”:

. . . this searing glow

Will grow, will spread, roots of fire, shoots

Of light, leaves like tongues of flame, stark

Blossoms of burning truth: will still and always throw

Out rays that rise beyond the deepest of all nights.

The tension between the fire of hope as a creative force and the fire of despair as a destructive one plays out in “January 1990”, a poem that begins with a haunting declarative—“My days are now filled with the sounds of fire”—then moves through descriptions of “the cracking and rasping of fields set ablaze” and “the drone as the planes rise, / Prelude to the dark fire flung from the sky” before turning on a line that acts as a conscious echo of the opening:

I will not submit to such fire.

Manganaro indents this for emphasis, and from here the poem—much like “For Peter: 29 January 1989”—lifts on incantatory rhythms:

I will seek to raise

A song of praise that stuns to silence all

The strife and strident fire sound. I will spend

My life, soul, self to break the hold

Of hell here. I will set my hands to heal

The scorched earth; the burned and broken I will tend

Till this land shall learn some new true fire to build.

For me this poem has value as a marker of Manganaro’s spiritual maturity. Unlike earlier poems like “2/28/77” or “6/2/77” that present love as a leave-taking, a flight upwards into bejeweled skylines or starry nights, “January 1990” shows it as a movement into the mire, a Christlike descent into closer association with others in their suffering. When she writes of “seeking how / Best to share their terror of the wrath”—“their,” of course, referring to the war’s victims, a war they had no hand in starting—it strikes me as just about as concise a description of Christian witness as I have ever encountered. One thinks of Rutilio Grande and Oscar Romero, of the two Maryknoll sisters, Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, who were brutally murdered by the Salvadoran military in December 1980 and are buried in Chalatenango, not far from where “January 1990” was written.

Unbeknownst to her at the time, Manganaro had only three years left to live and two left to write. The remaining poems in the collection include portraits of Salvadorans and fellow aid workers; poems that serve as emotional or spiritual calls-to-arms to help herself and her friends—and I count her patients as her friends, so clearly is her love for them evinced—push “through all the length / Of death’s long darkness” and find a place of light and strength; and even, tucked away amidst the images of war, a poem that sings back tenderly to Kavanaugh like a signal through the flames. In 1993 her cancer returned, forcing her to leave El Salvador. She died at her mother’s home in St. Louis that June.

There is another poem in Give Me a Living Love that I admittedly overlooked on my first few readings. “End of the year, 1991” seemed a bit quirky, with a self-consciousness that felt out of place within the Salvadoran sequence. “I am one of the following, choose the appropriate / Response”, it began, then moved through a series of correlatives that grew increasingly grave: “a handy reference book”; “a magic mirror”; “the stone / Against which you sharpen your mind’s striving”; “a tool to keep your steel soul keen”. Something about the poem kept drawing me back, though, and I began to see it as a statement of Manganaro’s poetics, the story of the book itself that is the story of her life. The final two lines imagine this book as illuminated manuscript, then promptly undercut the claim with a terse dose of spiritual self-honesty:

I am a lens to filter and focus the arriving

From afar light: I am none of the above.

It makes sense, with a life so other-centered as Manganaro’s: in all of her works of mercy, as in all of her poetic lives, she kept herself completely open to the movement of the Spirit. She had to be “none of the above”: only God could define her. ♦

Michael Centore is the editor of Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!