A Rhythm Runs Through It by Kathryn Sadakierski

Holy Land: Poems

By Angela Alaimo O’Donnell

Paraclete, 2022

$20 (paperback) 108 pp.

I

Following Love in the Time of Coronavirus, about pandemic-induced containment, Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s latest poetry collection, Holy Land, is refreshing in reaching past worldly spatial limitations to touch the divine. Wanderlust is reimagined not as aimlessness, but as a yearning for God, recalling St. Augustine’s famous quote that “Our hearts are restless until they rest in You, O Lord.”

Arranged into six parts, Holy Land’s poems are presented like phases of a pilgrimage as readers venture with O’Donnell on an international excursion, accompanying her on stops along the way. We are not jolted from one time zone to the next, made to feel jetlag or whiplash from the traveling, but are given a sense of the fluidity of time, of how full-circle the life in the church, and life in Christ, is. The poetic narrative that emerges follows a rhythm of rising, dying, and rising again, seasons and peoples of the church in each of her states connected.

Rather than reading like separate legs of a trip divided into discrete categories, the poems flow from one to the next. Each becomes its own scenic vista, where one may step out with the author and reflect on what lies within and ahead. We come to understand wholeness in Christ as reflected through these transitions that are presented as part of a broader journey. Akin to a table laden with many dishes—some comfort foods, some unfamiliar cuisine, all contributing to a sumptuous feast for the senses—the subtler accents of Holy Land bring out a variety of flavors that whet the appetite of all readers, whatever their literary sensibilities may be.

This sharing of nourishment is ultimately about entering into communion with Christ and other members of his body, tasting the richness of each season in life. Capturing the unique transcendent beauty of each place—the “everlasting rain” of Ireland versus the sun-dappled airiness of the Middle Eastern terrain, to name just one example—the gaps between geographic locations are bridged as O’Donnell explores the holy land of the soul, the internal resource to be tapped into, affecting how everything is seen and felt.

The first “course,” so to speak, recalls O’Donnell’s visit to the Middle East as she travels through the Holy Land where Christ set foot. As the poems in this part and subsequent sections illuminate, through these steps he touched the entire world. O’Donnell compellingly recreates well-known Scriptural scenes including Christ’s calming of the sea, reframing them not as stories of the past but mirrors of present realities, narratives with current implications affecting us all. The effect is to express that salvation history unfolds now as we shape it through all the places we touch, and that have touched us, as God’s hand guides every experience. Spiritual development is constructed as ancient yet ongoing; every spiritual journey is interlinked as the paths between Christ and his followers overlap. Jesus is woven into every interaction. We go with him to Calvary and back, peering through a sacramental lens as he breathes new life into all places, even the seemingly unreachable interior ones.

In this section, “The Thief” is an exceptional poem of crystalline wisdom and beauty, a fresh lens through which to view the hemorrhaging woman’s tale of suffering and redemption, so reflective of Christ’s paschal mystery itself. Exemplifying O’Donnell’s skill in penning poems whose intriguing layers of meaning encourage further readings to fully unpack their depth, “The Thief” is one of many that make Holy Land a joy to revisit. Every character we meet comes to be known intimately in terms of their identity in Christ, drawn up in the tapestry of the universal church. So, too, are they illuminated as individuals made in the image of God, exemplifying his creativity and generativity in making meaning, coaxing light out from the darkness of isolation that we may feel at times as earthly travelers in exile from Eden. And yet, the hope of an Eden-like pulchritude is not absent from the collection, where readers may glimpse the heavenly promise of total heart-unity with Christ and all creation, a feeling of connection to things of eternal beauty that surrounds.

In “The Thief,” we arrive at a heightened understanding of the gospel story, regarding it in a new way as we empathize not only with the physical ache of the hemorrhaging woman, but also her emotional pain, her yearning for a deeper healing. Synthesizing the gospels with Greek mythology, Midas’s golden touch becomes the blood of Christ healing the rupture, the eyes unblind to suffering, the hand extended in care and compassion. Broken heart having once bled, the woman’s spiritual pain is remedied; the ground she dragged herself across to reach Jesus is transfigured for having borne her across to a higher plane. O’Donnell bears eloquent witness to the woman’s dedicated faith. Her writing reveals the process, not the product, of the healing, which speaks volumes. Under the poet’s deft hand, we appreciate the lengths the hemorrhaging woman went to for Christ in carrying her personal cross, the broken body paralleling the lengths he would go to for her.

There are also parallels between this story and that of the “Good Thief” made in the poem, marking the narrative as one of redemption, of giving and opening the heart to reception of God’s love rather than taking. Speaking into the woman’s reborn existence, subsequent poems capture stolen moments, fleeting sights, and sudden epiphanies manifesting God’s everlasting love, opening our eyes to his presence in even the most unexpected places. O’Donnell’s greatest achievement in this collection is to show us that we are part of the miracle as well, capable of building a better world through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit so that the rubble of past trials is transfigured. “Long after his dying she would live,” O’Donnell reassures us, testifying to the Spirit that outlasts all places and people.

II

Imbued with Ignatian spirituality, Holy Land encounters God in all things, emphasizing his omnipresence in how light filters through every time and place, serving as a connective thread of the collection. Holiness is not inaccessible in these poems, but visceral, real, pulsing in every vein. Every experience recounted provides the opportunity to lean into spiritual growth, to come closer to God by caring for his creation. Faith is very much alive in the changing landscapes we traverse in the poems. “How rare the saint who homes,” O’Donnell writes, emphasizing that growing in holiness is not about stasis so much as continual movement, not giving up, continuing the route to God inwardly and outwardly, however circuitous it may become. Outer dwellings reflect the indwelling of the ever-present Spirit.

More than a geographical location, O’Donnell’s poetic conception of “holy land” is a place unbounded by latitude and longitude, encompassing a beatific vision of home and how we become who we’re meant to be within the kingdom of God. A home, then, may be made anywhere when rooted in Christ, carried forward by his spirit of mercy and hope that we can come to imitate as we advance in our walk to and with him. Insights like these add dimension to the poems, which are already dynamic thanks to evocative, atmospheric descriptions that crystallize the bittersweetness of experiencing earth’s ephemeral resplendence—of coming only to go, to adapt to one change before being transformed again by a fresh place and time. As O’Donnell has it: “The slow slope of light eases the grace / under all the suffering and sorrow.”

It is humbling to encounter the universality of suffering, the feeling of being an outsider in a new land, through O’Donnell’s travels and her ambles through the stories of the Bible. We’re made to feel at home with Jesus, the one who was unafraid to look at suffering and take measures to mend it (as in “The Thief”), no matter the cost, because he knew what it felt like to be an outsider.

Such a quest for belonging results in a kind of blessed fulfillment as O’Donnell, a pilgrim in Ireland, the motherland of her husband’s ancestors, realizes in one poem that “my foreign heart [is] more native than she seems.” While initially feeling out of place, outwardly perceiving that she doesn’t fit in, she ultimately connects with the spirit of the country: the feistiness and wit of locals who wax poetic with American visitors about “Barack O’Bama,” the sense of reverence for the sacred that is sensed amidst the mossy graves in cemeteries, whispering of those passed on to the next life but never truly gone: “small comfort in the face of the mystery / not having to endure it alone.” Here, as throughout the collection, the promise of rising, of an elevated spirit that is buoyed by hope, prevails in the immortal soul of the land.

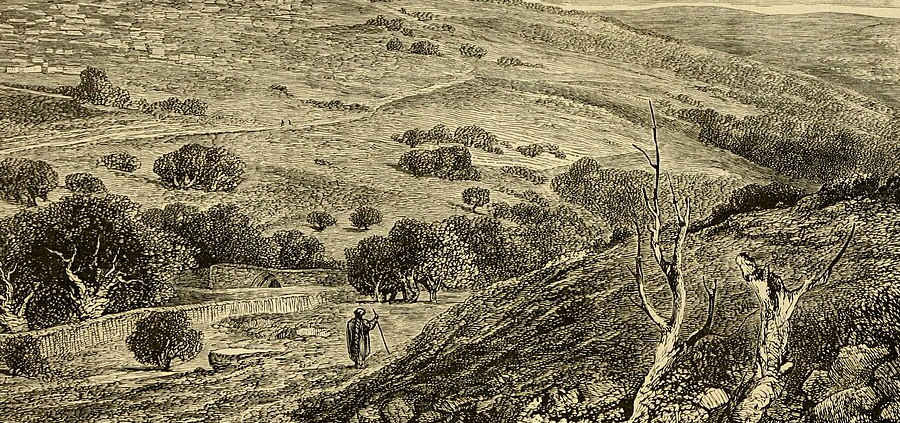

Simon Jordaens, “Christ Heals the Bleeding Woman,” 17th c.

Balancing tensions between the local and global, Holy Land tackles issues such as the crisis at the US southern border, incisively communicating that the global is the local, that heartache experienced by another the heartache of oneself. O’Donnell’s poems in a sequence entitled “Border Songs” are peopled with speakers who mourn children, who sing and marvel at the vastness of the heavens, who pray decades of rosaries with the decades of their experiences etched into their faces and the deserts they wander through. Every soul, we learn, is valued by God, like the inconceivably grand vistas we revel in seeing and where the light of potential, of hope for what can be, cracks through, cutting past the knife’s edge of impossibility:

Nothing is bluer than the Texas sky.

It lifts my heart. I don’t know why.

At night it goes black. Then I see the stars.

Tender portrayals of parenthood, of how our homes hold us, comforting us in times of uncertainty when the world may seem unnavigable, suggest the nurturing nature of God. Displacement and disquieting unsettlement are juxtaposed against images of serenity and security: a baby held on a sleepy winter morning, the voice of hope born amidst wordlessness: “Against this morning’s silence I write / something into being, something true.” The lines nestle into heart with the solid sureness of an infant’s head on one’s shoulder, grounding the poem and speaking to O’Donnell’s ability to distill simple moments to their most essential parts, their great significance that stirs the soul.

The landscapes O’Donnell immortalizes are themselves living poems, God’s offerings. God is the rhythm running through the network of places, his lyrical movement working in all things like the Pentecostal winds buoying inspiration or the Holy Spirit alighting as tongues of flame to spark the spiritual imagination of each soul. Traveling emotional distances from grief to renewal, Holy Land unflinchingly beholds brokenness, but in the context of its reparability. Humming under the surface of everything, the unbroken rhythm of the Word is audible. Halves are brought together and made whole; as the poetry of everything is acknowledged, as is God, the crafter of each verse.

III

Though she ranges across a variety of topics, emotions, and locales in her foray through spiritual and corporeal realms, O’Donnell remains consistent in form and technique. A less seasoned poet’s perfect rhymes may feel singsong or trite, but hers have a certain timeless quality lending itself well to speaking of the sacred, in the style of a chant that strikingly conveys images: “the moon, earth’s companionable ghost, / the world’s blessed and broken communion host.” Favoring sonnets, she has a penchant for formal metered verse rather than freestyle writing, which intensifies the focus on her chosen subject matter. Poems have the weightiness to hit home thanks to their brevity, the thread cut at just the right moment so that the reader may pause and think before picking it up again subtly in the next poem.

Between each season, liturgically and personally, there is a holy waiting, a dwelling in in-between spaces before moving forward then discovering; reaching the manger, reaching the cross. Contemplation precedes action, as one then goes back to the community to tell of being transformed by these travels. A missionary zeal stretching back to the early church is palpable, fresh with the promise of the new evangelization. The poems become a celebration of the power of words, of how writing transports us, preserves our identities, and broadens the scope of our being, of our experiences.

This theme is most clearly defined in a section called “Literary Islands,” but what becomes evident is that inspired literature connects us to the extent that we are no longer “islands.” We get a sense of our own complexity, all the lands we’ve crossed and people we’ve been, braided together like Christ’s unified identity as God and man. Existing herein is a trinitarian consciousness of past, present, and future, our identities in God, reflected in the places we’ve laid down the roots of our faith and where we’re passing it on to future generations, opening ourselves to the adventure of following Christ, wherever his plan will lead us.

Whether it is the Bible or a book of poems like Holy Land that praise the Word-made-flesh, the words that keep traditions alive—traditions like pilgrimaging to the altar at each Mass, or waking up to a new day and venturing into it to proclaim the Good News—are what simultaneously cradle and challenge us. Through reading Holy Land, there is the potential for an expansion of worldview, of other-awareness, but also for a winnowing, a carving away of the self-serving spirit to better love others, be better stewards of the land, and give of the self to trust in God’s roadmap, his design for each of us. Amidst weddings and funerals, previously untrekked pathways and states in life, from lands of daughterhood to lands of motherhood, Christ is at the center, holding all that O’Donnell poetically remembers together.

An inquisitive spirit, a divine curiosity, pervades Holy Land, which poses questions of how we chart our course and determine what mark we will make to bring Christ’s light into the world. How do our identities change according to our relationships with land, people, or stay the same, even when what we have fades away? How do we memorialize what has passed, in a kind of mobilized anamnesis? We are called to consider how we inhabit our own present places, and how the lives we lead today reflect the thoughts of our hearts. Our readerly imagination shifts from our temporal to our eternal destinations, so that we note their overlap, weighing how we might ease our neighbors’ burdens to make earthly life more heavenly. There are no pat responses to the queries put forward. Instead, we are absorbed in the enigmas puzzled out in the verse, led to trust that God will be with us, even when we don’t know where we are headed, knowing that the One who is the answer will reveal all in time, when we are ready.

Making for excellent reading material in the season of Pentecost (bonus points if on a road trip), the season of the journeying church, when she is born and built, coming into her own, Holy Land’s call to action is to keep the flame of hope burning, to lift our voices to shed the light of Christ so that others might share in what we have and pursue their callings, treasuring Christ’s body, God’s created land, people, church: “We were warned about the weather / but we made the journey anyway . . . / And when the weather was bad, we sang.” No ordinary time exists in Holy Land, with all experiences rendered extraordinary when seen through the brightness God’s eyes. Indeed, “We start the story to get to the end,” though, we might add, to return to the beginning, remembering our purpose, why we live our faith. The collection leads one to want to begin again, to reexamine and keep the eyes of the soul ever open to possibility, returning to the first verse for yet another journey. ♦

Kathryn Sadakierski’s writing has appeared in Agape Review, DoveTales, Edge of Faith, Ekstasis Magazine, enLIVEN Devotionals, Refresh Bible Study Magazine, and elsewhere. She holds a B.A. and M.S. from Bay Path University. Kathryn is passionate about sharing her love for God through her work, with the goal of making a positive impact.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!