The Revolution of the Children of God: Guillermo Rovirosa and His Thought by Gregory Fox

Note: We wish to acknowledge that the beatification process for Guillermo Rovirosa is currently open—Ed.

As a Spanish Catholic, working-class militant, and anti-Francoist activist, Guillermo Rovirosa (1897–1964) would perhaps strike many contemporary readers as an unusual figure. When one thinks of Catholics and the Civil War in Spain, the first word that comes to mind is usually not something like “anti-Francoist.” Understandably, the popular image of the church and Catholics during that time is one of political reaction and conservatism, and ultimately of collaboration with fascism. Nonetheless, there were exceptions to this capitulation and temporalization of the church. These exceptions, like Rovirosa and others, deserve to be remembered.

Though Rovirosa’s name may be occasionally found in academic literature on European Catholic Action movements—for example, Gerd-Rainer Horn’s 2015 book The Spirit of Vatican II: Western European Progressive Catholicism in the Long Sixties—outside of these academic circles (or certain Catholic circles in Spain) his work remains almost entirely unknown. This is regrettable, since Rovirosa’s life and work (as we will see) breaks many of the stereotypes and worn-out clichés which Catholics of all persuasions have become accustomed to repeating about the role of their coreligionists in the Spanish Civil War and Franco era.

Youth

Born in Vilanova, Spain, on August 4, 1897, Rovirosa grew up in a humble Christian peasant family. Rovirosa’s father, José, as he recalled in a short autobiographical article published by the French left-wing Catholic journal Témoignage Chrétien in 1956, instilled in him a sense of devotion to the “culto de la verdad.” Likewise, his mother, Ana María, was “a woman of extreme religiosity and piety” whose life-long suffering—and eventual death—would have a profound effect on him.

Two years after the death of his father in 1908, Rovirosa was enrolled in a Piarist school, a religious order established by Joseph Calasanz in 1617. During his time at this school, Rovirosa would lose his Christian faith.

Religious Crisis

During his time at the Piarists, Rovirosa encountered much “religious education” but very little teaching—as he later recalled—on “the person or the message of Our Lord Jesus Christ.” This lack of authentic religious education, combined with his mother’s deteriorating health, contributed to a growing crisis of faith.

Since his youth, Rovirosa’s mother struggled with paralysis. Rovirosa recalled that his mother would at times thank the “buen Dios” for bringing her “close to him on the cross” through her suffering. Rovirosa found his mother’s posture of openness to God in the face of her suffering to be incomprehensible, since, according to him, the contradiction between “what [his] mother deserved and what life had given her” was stark.

Rovirosa’s mother died in 1915, when he was 18 years old. This event caused a complete break with Christianity. Religion, Rovirosa believed, was a “hoax, organized by cunning people[.]” Thus, between the years 1915 and 1932, Rovirosa looked for truth in various philosophies and religious sects, such as theosophy and spiritism. By the end of this period, he found himself completely convinced of skepticism and materialism.

Professional Life and Marriage

Alongside his search for religious and philosophical truth, Rovirosa advanced in his professional life. In 1917, just a few years after his mother’s death, he entered engineering school. During this period he contracted tuberculosis and was unable to finish his courses. Four years later, in 1921, he published two books on electrical engineering.

In 1922, Rovirosa married Catalina Canals. One year after his marriage, Rovirosa’s brother-in-law died, an event which only deepened his religious crisis. This, along with the death of his mother, constituted for Rovirosa a “brutal contact with the world”.

A few years later, in 1929, Rovirosa and his wife had moved to Paris. In France, he found employment as a worker in a factory located in Compiègne (Oise).

Reversion

Rovirosa’s religious crisis would find itself, to some degree, resolved near the beginning of the ’30s—specifically in 1932, the year he credited as the beginning of his conversion to Christ and the gospel.

One day while he was in Paris, as José Andrés-Gallego recounts in his 2014 article “Christians in Search of Non-Christian Certitudes,” Rovirosa noticed a small crowd forming around a church. Intrigued, he asked what had caused it to form. As it turned out, Cardinal Jean Verdier had been preaching at the Institut Catholique de Paris. As Rovirosa listened to Verdier, he recalled one line which affected him quite deeply: “the best Christian is the one who knows Christ best.” Realizing that he did not really know Christ as a historical human being at all, but only an ossified “Christianity,” Rovirosa endeavored to discover Christ by reading as much literature as he was able to get his hands on—for example, Francois Mauriac’s Life of Christ and Augustine’s Confessions.

Commitment and Militancy

On Christmas Eve 1933, a year after his encounter with Verdier, Rovirosa made what he calls his “second first communion”. From 1934 onwards, he encountered what he called the “marvelous Christian synthesis”: “the Incarnation, the Life and the Doctrine of Jesus, summed up in one word: Communion. All summed up (for the faithful) on the triple solid foundation of Communion of Life (Humility), Communion of all kinds of goods (Poverty) and Communion of Action (Sacrifice).” The practical manifestation of this triple doctrine was found in Rovirosa’s involvement in the “working-class apostolate”—an attempt by the church to “recover” the working class in Europe. Rovirosa took this Christian synthesis into the crisis which would shake Spain in 1936.

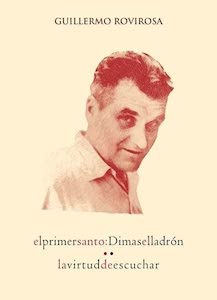

Cover of “El primer santo: Dimas el ladrón. La virtud de escuchar” (“The First Saint: Dismas the Thief. The Virtue of Listening”) by Guillermo Rovirosa (Editorial Nuevo Inicio, 2021)

According to Gerd-Rainer Horn, when Civil War broke out in Spain, “[Rovirosa] was unanimously elected to preside over the workers’ committee which henceforth administered the plant in Republican Madrid”—that is, until he was imprisoned by Nationalist forces after the fall of Madrid.

In the ’40s, Rovirosa carried this experience of working-class self-organization with him into the world of Catholic activism, and more specifically to the sphere of the “working class apostolate”. In 1946, he was involved in the formation of what was, in essence, the practical expression of this apostolate: the Hermandad Obrera de Acción Católica (HOAC). The HOAC was an organization (barely tolerated by the Franco dictatorship) which attempted to have “a consistent programme of training workers to become apostles of a better future amongst their cohort of working-class poor,” as Gerd-Rainer Horn argues. While this ambition was not entirely apparent at the beginning of the organization—which seemed to be focused mainly on journalism at first—after the suppression of the HOAC paper Tu! by the Franco government in the early ’50s, it moved into a more concrete direction of working-class education and formation.

In the form of the HOAC, what can only be described as a grassroots form of Catholic “workerism” emerged in Spain, with Rovirosa playing an important theoretical role in this process. In fact, unlike many forms of Catholic Action from the beginning of the 20th century, the HOAC was largely against what it called “paternalism and asistencialismo”. For example, as Enrique Berzal de la Rosa points out in his doctoral thesis Del Nacionalcatolicismo a la lucha antifranquista: “One of Rovirosa’s obsessions was to neutralize the opinions of those who minimized the intellectual qualities of the worker.” This anti-paternalistic tendency led Rovirosa to, as Gerd-Rainer Horn states, “develop a systematic plan to train HOAC rank-and-file activists to become spokespeople for their own class.”

Rovirosa’s thought should be recovered precisely in a period such as our own, where there is a renewed sense on the part of some (both Catholic and non-Catholic) of the need for working-class protagonism and self-organization. Therefore, to better understand Rovirosa’s contributions to Christian spiritual thought, alongside his contribution to this question of working-class self-organization (understood from a distinctly Christian point of view), I present the following excerpts that I believe to be useful examples of his ideas. The translations from Spanish are my own.

♦ ♦ ♦

Spirituality: Christianity as Total Friendship

For a long time, Christianity, under the influence of diverse philosophies, conceived morality, the ascetic life, more as an attempt to reach an ideal perfection, an abstract and impersonal absolute, than as a relation with a person, even if this person is God himself.

Under the breath of the Holy Spirit one has entered into the “Imitation of Christ”. Wanting to be humble is not the same thing as imitating the humble Jesus, etc. This, above all, avoids the danger of complacency, to the benefit of an authentic humility. This has been a great advance. But we cannot remain in the historical Christ . . . we must refer to the total Christ, where reality exceeds the maximum desires that man can have.

In order for us to arrive at friendship with God, the Word not only became flesh, and is found in the Tabernacle, but multiplied his presence (by Holy Grace) in every one of those that surround us, making each man a participant in the divine nature, and revealing to us that the most intimate essence of divinity consists in a friendship shared in Love, he has poured out this Love into all flesh, in order that we may “become like gods”, uniting ourselves with our brothers in Agape[.] . . .

Therefore, all religion is reduced to a friendship, not only with God, but with Jesus Christ and for Jesus Christ and in Jesus Christ with all men. The Christian is not only a friend of God (which in some way is certain in every religious man) but what distinguishes him in a particular and direct manner is that the Christian is the friend of all men.

– From Reflexions Militantes Cristiano (1989)

Working Class Militancy: Christian Working Class

The Christian working class must impregnate its solidarity, its anguish, and its revolutionary spirit with the exigencies of the Reign of God.

Historically. The solidarity of Christians is its central force: the entire Christian idea conspires to this: all the sons of God, the Mystical Body, the Communion of Saints, all history of the past twenty centuries demonstrates this: Christians united are invincible.

Sociologically. The progressive establishment of the Reign of God on earth, which is the central mission of the Church, requires this persistent anguish that has been one of the fundamental characteristics of all the Saints of the Church.

Theologically. Christ has come precisely to exalt the poor and the oppressed and to save all that was lost. This revolution that He began must be continued as a theological requirement.

Neither “Homo economicus” . . . The man of the working class must overcome the mentality of the homo economicus considered by many as the ideal type prepared to attain human perfection on earth. . . .

—nor “homo politicus” . . . The man of the Christian working class must also overcome the mentality of the homo politicus that was extolled by certain Greek philosophers and that today constitutes the ideal of the communist and of all the totalitarianisms (more or less camouflaged), which think that “political domestication” is the basis of a perfect society. . . . Sadly there are too many Catholics that believe in the efficacy of coercive methods (physical or moral) for the establishment of the Reign of God;

—but “homo theologicus”. The man of the Christian working class must be truly a homo theologicus so that his solidarity may have a solid foundation, with the purpose of his anguish being truly constructive, and so that his revolutionary spirit may be framed in the spirit of Christ.

The man of the Christian working class must work with all his strength, and these are of three orders:

Material, and all matter, including his body, must be engaged in the struggle for the Reign.

Spiritual, all science, art, culture . . . must enter into action in the service of the Christian Revolution.

Supernatural, this is the fundamental asset since it gives us the certitude of being truly in “God’s line”. . . .

One must seek first the Reign of God and his Justice, we must struggle so that this Reign arrives and so that the will of God is done on Earth as it is in Heaven. Then there is peace, well-being, joy . . . not as a supplementary gift to the Reign of God, but as something that is united to it intrinsically.

Truly this is to make the Revolution of the Children of God.

– From Una doctrina de los movimientos obreros cristianos (1954)

♦ ♦ ♦

Gregory Fox is an independent researcher based in Virginia whose primary focus is the history of social, democratic, and liberal Catholicism in 19th- and 20th-century France. His previous essays for TAC include “‘A Sublime International’: The Life and Work of Leon Chaine” and “Personalism and Production: On Virgil Michel’s Social Thought”.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!