The Pace of Rome, the Peace of Ireland by Julie A. Ferraro

When I originally started writing this column, the hectic pace of Rome, Italy, had me in its clutches. I admit, my every nerve was on edge from a week of fitful sleep due to the heat, humidity, and noise of that historic city.

I’d traveled from Idaho as a delegate to the Fifth World Congress of Benedictine Oblates, held September 9–16 at the Collegio Sant’Anselmo. The theme of the congress was “Moving Forward: Living the Wisdom of the Rule.” That’s the Rule of St. Benedict, of course.

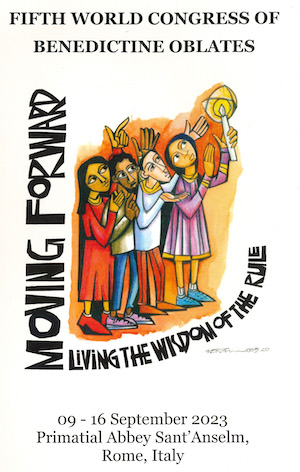

The logo for the Fifth World Congress of Benedictine Oblates created by Br. Martin Erspamer, OSB (Courtesy Fifth World Congress of Benedictine Oblates)

Approximately 150 oblates from 25 countries, representing over 80 monasteries, gathered for the event, which previously took place in 2005, 2009, 2013, and 2017. A lapse due to Covid-19 delayed this year’s congress from 2021.

The diversity of cultures and languages might have created quite a Babel, but the common excitement of being together elicited a patience not usually present in some international, politically motivated assemblies.

Three keynote speakers gave presentations on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday, with excursions to Benedictine landmarks of Monte Cassino, the Sacro Speco at Subiaco, and a private audience with Pope Francis occupying much of Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

Workshops broke the delegates into small groups for discussions about what the keynote speakers had shared on the topics of oblate formation, evangelization, and expanding the mission of the monasteries with which they are affiliated. A “hot topic” was how to reach the younger generation, since most of the delegates were older. The numerous influences on those young lives—both positive and negative—creates a challenge for those wishing to share the inherent balance of Benedictine spirituality.

The consensus: lead by example. Abbot Donato Ogliari of the Abbey of St. Paul Outside-the-Walls in Rome ended his talk on evangelization with the recommendation that oblates should be the St. Benedicts needed in today’s world.

In my estimation, he should have started his talk with that statement and built on it. This was a large part of my frustration with the congress. The presenters weren’t oblates, but vowed religious, selected not by the oblates on the core team planning committee but by other vowed religious.

Sister Marie-Madeleine Caseau, OSB, prioress of Sainte-Bathilde in Vanves, France, spoke in French (with simultaneous translation into the other languages) at great length on formation, citing extensively from St. Irenaeus. Not that that’s a bad thing—if you’re a graduate theology student. Addressing the modern challenges of instructing oblate inquirers and those who’ve been oblates for decades might have been more practical and informative.

The third speaker, Abbot Primate Gregory Polan—who served as abbot of Conception Abbey in Missouri prior to moving to Rome—read from his prepared text in a monotone, showing little enthusiasm for meeting the delegates themselves.

My question has to be: Why weren’t oblates given a greater role in planning their own congress? Why do the vowed religious still see themselves as needing to preach to the laity, to dictate their activities? Oblates continue to be seen in too many places as a subcategory of Benedictines, with no substantial position beyond serving the needs of their respective monasteries as volunteers or donors. They hold no decision-making authority in their monasteries or among themselves.

If Benedictine spirituality is to move forward, however, this has to change—radically.

In some places, it is. The Center for Benedictine Life at the Monastery of St. Gertrude, Cottonwood, Idaho, St. Meinrad Archabbey in southern Indiana, and a number of other monasteries have implemented lay leadership models for their oblates.

Another frustration came at Monte Cassino, when the abbot, Dom Antonio Luca Fallica, celebrated Mass in the ornate basilica. After the Liturgy of the Word, with the readings in English and his homily in Italian, he proceeded with the Liturgy of the Eucharist with his back to the congregation. I hadn’t voluntarily sat through Mass that way since I was a small child during the Second Vatican Council.

Word was that the way the sanctuary is constructed, it’s not possible for an altar facing the people to be added. My response: other churches have determined ways to make this happen, and I think St. Benedict would’ve wanted those visiting this edifice where he spent so much time—and where so many died during World War II—to feel welcome.

Two incidents tempered this series of annoyances, fortunately.

On Friday, after climbing nearly 200 stairs—panting and gasping most of the way—at the Vatican for a private audience with Pope Francis, he imparted more wisdom and inspiration in his brief address to the oblates than the other three congress speakers combined. No one left the Clementine Hall unmoved by his quiet humility and fascination with a small child in the crowd.

Then, en route back to the States, I spent time at Kylemore Abbey in Ireland. The Benedictine Sisters of that small community welcomed me, and I reveled in the quiet beauty of the Irish countryside on a Sunday morning, low clouds embracing the mountain tops.

I regained the peace I missed so in Rome, and I’m incredibly thankful for that. Still, I hope that as the Benedictine family moves forward guided by the wisdom of St. Benedict’s Rule, the oblates will be viewed by their vowed counterparts as equals, allowed to evolve Benedictine spirituality in this 21st century and share it with those in the world who hunger for it so desperately. ♦

Julie A. Ferraro has been a journalist for over 30 years, covering diverse beats for secular newspapers as well as writing for many Catholic publications. A mother and grandmother, she currently lives in Idaho. Her column, “God ‘n Life,” appears regularly in Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!