A Pilgrimage in Parallel by Bob Toohey

Pilgrimage: an inner journey precipitated by an outward experience.

The Atlanta International Airport was bustling with travelers as my wife and I waited to board a flight to Israel. We were headed for a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, a trip we had dreamed of for years and had been planning for months. In the city of Cana, we would renew the wedding vows we made 49 years ago. As we chatted with the group we were traveling with, I was called to the agent’s desk. “I’ll bet my frequent miles have earned me a seat upgrade,” I thought.

At the desk stood two police officers. One said, “Mr. Toohey, you need to come with us.”

“What is this about?” I asked.

“We have a warrant for your arrest,” he said.

My wife started to follow, but they ordered her to stay there. I glanced at her and tried my best to look calm and assured, saying, “Don’t worry, it’s a mistake. I’ll be back in a minute.”

I was escorted to the basement of the Atlanta International Airport. Another group of officers met me there and demanded I empty my pockets. “What’s going on?” I asked.

The superior officer said, “We are arresting you as a fugitive from prosecution.”

“What is the charge?” I asked in disbelief. He replied, “You have a DUI charge in the state of Alabama from 2000.”

“That’s impossible,” I said. “That was 23 years ago. I’ve traveled all over the world since then. My wife and I were just about to board a plane for a pilgrimage to Israel.”

His response was curt: “You won’t be getting on that plane or any other plane today.”

I was allowed to call my wife before surrendering my phone. I told her I had been arrested and to go on to Israel without me. “I’ll be OK,” I said. “It is some kind of clerical mistake that may take some time to work out. I love you.”

I was confused and terrified, but mostly saddened and concerned for my wife who was left to face the consequences of my actions one more time, even after 23 years of happy sobriety. In those years I had learned that no matter how dark the situation seemed, there was a loving power watching over me. What I did not suspect was how dark this situation was going to get.

And thus began my pilgrimage of an entirely different sort.

Booked

An officer shoved me into a small holding cell. He then patted down every inch of my body—the first of what would be a long series of humiliations.

For the next 30 minutes I sat alone, repeating to myself, “Is this really happening?” I was reeling in anxiety and confusion. I fought back tears as the new reality set in. I thought of how alone and afraid my wife must have been as I sat and shivered, waiting for what lay ahead.

A large deputy handcuffed me behind my back and led me through the main body of the airport, past ticket counters and excited travelers. Children gawked at the “bad man” being paraded through the airport lobby. I prayed I would not be led past my wife as she boarded her plane.

As I entered the Clayton County Jail in Jonesboro, Georgia, I noticed the mosaic tiles embedded in the floor of that read: This is the “Hillton” – Sheriff Victor Hill’s House – My House – My Rules. The corrections officers were all over six feet tall, broad, muscular, and intimidating. They wore black uniforms, knee-high black leather boots, and thick vests, with gleaming pistols and handcuffs strapped to their belts.

The officer took me to a room where I was frisked once more and ordered to shower with him observing. Afterward, he issued me an orange jumpsuit I could barely squeeze into and a pair of plastic flip-flops so small they cut into my feet with each step. I was not issued a pillow, blanket, toilet paper, or toothbrush. When I asked about this, the guard said, “You’ll get it when we get it.”

I learned in stages that surviving here was a matter of doing what you are told. While an officer led me down the jail corridor to my cell unit, I passed by non-prisoners. Suddenly the officer jumped within inches of my face and shouted, “Get your f***in’ a** against the wall when someone passes you!” This is how I would learn. I had no orientation. I figured out what to do and how to do it by being reprimanded.

Up until this day, I was a successful safety professional, a long-time husband, a poet, a spiritual retreat leader, a mentor of over two dozen men in recovery from addictions, a father of five and grandfather of seven. Yet here in this jail, no one knew or cared. I was just one more convict in an orange jumpsuit and flip-flops. Soon my sense of who I was would go underground and a new identity would emerge—that of another prison inmate.

Moving Into My Cell

My assigned unit held 20 cells. Each cell had two metal platforms to hold our plastic sleeping mats. It seemed everyone knew what to do but me. Should I wait to be assigned a cell? I watched as the other new inmates quickly claimed one. What was I to do? There were no directions, no orders. It was every man for himself.

There were two cells left. Both had toilets leaking across the cell floor. I chose one and put my plastic pad on the bottom bunk. I stepped outside, grateful that I had a cell to myself. From that moment, every time a new inmate arrived, I hoped and prayed he would not pick this cell.

I stepped out onto the mezzanine outside my cell that looked down on the general assembly area. Standing next to me was a man of about 30, medium height with a muscular build. He leaned on the rail as he looked out over the unit, chatting with others on the floor below. He looked at me and said, “Hey, ol’ timer, what are you here for?” “Ol’ Timer” became my jail moniker from that moment.

The average age in my unit was around 30. I am approaching 70. I was the only Caucasian in this unit. My new acquaintance must have been wondering how this old white guy ended up here. “A 23-year-old DUI charge I didn’t realize I had,” I told him. “Holy s**t!” he replied. “I’ve heard a few bench warrants catch up with dudes after two or three years—but 23?”

He poked his head in my cell. “Man, your cell is a mess. You can’t stay in that filth. Come with me, I’ll help you straighten it out.” I followed him downstairs, grateful for the first humane interaction since my arrest. He filled up a mop bucket and helped me carry it to my cell. His small act of kindness removed the terror I felt, and I started to come to my senses. My trembling stopped.

Jail Deprivations

I brushed my teeth with my fingers using the hand soap provided with the little trickle of water that came out of the faucet. Since my toilet did not work, I urinated in the sink. I borrowed sheets of toilet paper from other inmates. At night, I lay shivering in a fetal position on my thin plastic mat on a metal platform. All night I yearned for daylight to come through the window and warm up my cell. It would be two sleepless nights before I would get a blanket and pillow. I never got a toothbrush or toilet paper.

Our unit was in lockdown from 18 to 20 hours a day. We were allowed out of our cells for breakfast, and an hour or two in the evening. That is when you use the phone and take a shower. With forty men, six phones, and one shower, it was virtually impossible to use either in that short time.

I hadn’t eaten in over 24 hours, so the next morning I was famished. The orderlies brought in a large cart holding 40 brown plastic trays. The trays had four compartments. In one was a pancake the size of my palm—no syrup or butter. In another, a paper-thin slice of bologna. Then some meal mush I did not recognize and a dried can biscuit. I was issued a “spork” with my tray, but no one told me to hold onto it as it was the only one I would receive. I tossed it after breakfast. For the rest of my time, I ate with my fingers—oatmeal, powdered eggs, and beans.

All the tables were full except one. A young black man was sitting by himself. I felt it important for my sanity to try to make connections, to try to fit in. I pulled up to the table, sat down, and said, “Good morning.” He abruptly got up and moved to stand at a full table.

I felt embarrassed and spotlighted. I struggled to understand why he got up. Was he afraid to associate with the “old white guy”? Was he a past victim of racism, and I a symbol of that traumatic memory? I sat alone and quickly swallowed my breakfast.

After breakfast, we were given a plastic bag containing six slices of white bread, three thin slices of bologna, and three slices of Velveeta sandwich cheese. This would be our lunch and dinner.

I learned at my intake that I wasn’t eligible for bail since I was charged in Alabama and would have to wait for the state to extradite me. Alabama was in no hurry to drive over here to pick me up. I could expect 30 days at Clayton County Jail.

Shakedown

My unit teemed with anger and unrest during my first two days. Toilets leaked onto cell floors. We were short of towels, blankets, and toothbrushes. The phones did not work. The inmates shouted obscenities through the glass walls at the orderlies as they passed by. The shouts reverberated throughout the block-and-metal room as a continuous roar, subsiding only briefly, then erupting again through the day until lockdown.

One afternoon an officer came through the door of our unit and announced, “Up against the wall, a***holes, your sergeant is entering.” The inmates abruptly stopped talking and lined up with their faces against the wall. In a second, the unit went from pandemonium and anarchy to silent submission. Then in came the sergeant. He was at least six feet four, probably 240 pounds.

“Men, when you act like animals, I have no choice but to treat you like animals,” he said. “Everyone sit on the floor facing the wall with your hands behind your back. Eyes straight ahead.” We were frisked one by one as we sat on the floor. All gang machismo was gone, replaced by meek compliance. Then lockdown once more.

Dark Nights of the Soul

I have practiced contemplative prayer for over 25 years. I have built practices of silence and solitude into my life. I thought I would be just fine if I was ever thrust into solitude without being able to escape. How naïve!

During lockdown, I began to understand the psychic harm of forced solitary confinement. For hours on end, questions swarmed my mind. At first they were rational: “How long will I be here?” “Is anyone working on this for me?” “How is my wife coping while in Israel?” But, in time, I lost control of my cognitive processes and random thoughts appeared: “How many ceiling tiles are in my cell?” “If someone makes a movie about me, who will play my role?” “If I were stranded on a remote island, what three things would I want?” (That day, it was a blanket, a toothbrush, and a fork.) Fantasies, unconnected thoughts, one after another, going nowhere.

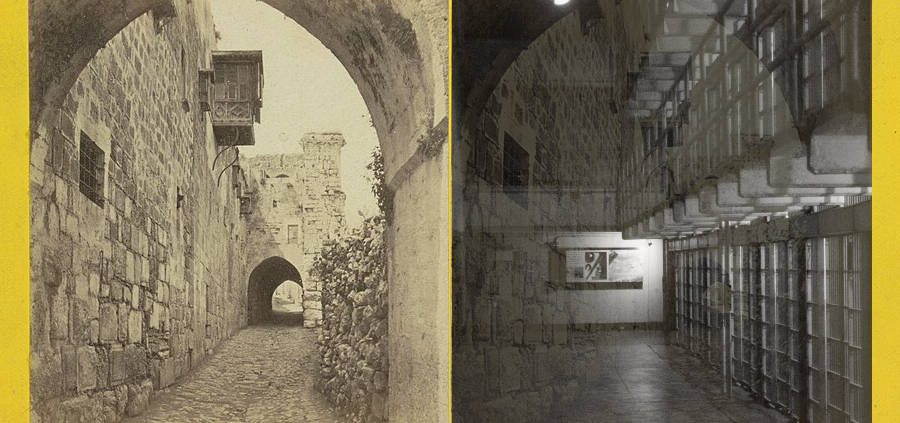

Image courtesy of Bob Toohey

I practiced the disciplines I had learned: contemplative prayer, prayers from Catholic school, and prayers in my recovery literature. I thanked God for the teachers and mentors who prodded me to memorize them. Was it for such a time as this, when they were all I had to combat my unruly mind? I even resorted to the rosary, which had never been my devotion of choice. But in the endless hours alone in my cell, the repetitive nature of the prayers as I thumbed the imaginary beads kept me sane. I grew to depend on this devotion during the long nights and days. They connected me to a loving God, and to my family and friends. I prayed for each family member and friend—I even began praying for those cellmates that I had conversations with. I thought of how they were navigating the mental struggle of lockdown. What tools were they taught? What practices, if any, could they rely on during the dark night?

The main objective of spirituality, contemplation, solitude, and meditation is to connect with God and to our fellow humans, not to separate ourselves from them. In solitude and contemplation, we allow ourselves space to erase all the illusory ways we divide ourselves from others. In a jail unit with 40 men, with whom on the surface I had nothing in common other than an orange jumpsuit and black plastic flip-flops, my prayer told me we had everything in common in the ways that truly matter.

In jail, we are all suffering, regardless of the masks or fronts we put on. I put mine on—the mask of the silent and wise “ol’ timer.” An 18-year-old who weighed less than a hundred pounds was in for aggravated murder. I heard him bragging about this act to his cellmates. It was his ticket to inclusion in the inner circle of my unit. He had no identity, no worth, and no connection to anything outside of this cult of violence and crime. Yet, time and time again I watched these young men drop their masks when on the phone with parents or girlfriends. Gone was the bravado, chest-thumping, and one-upmanship they carried on with during their free time; instead, they cried on the phone for their wives or girlfriends not to leave them, or for their parents to help them one more time.

I was able to reach my wife on the phone twice while confined. Each time was heartbreaking, yet I hung up knowing we loved each other and would come out of this stronger and even more in love. I doubted this was the experience of most of my fellow inmates. I knew from conversations I would have over the next four days that many had left a trail of broken relationships. As a result, they were disconnected from the help they needed. There was no one left in their lives who was willing to help.

And yet here I lay, in what might be the most brutal jail in the country, deprived of things that make life tolerable, staring up at the metal cot above, feeling most fortunate. This had become my pilgrimage. In my cell, I became aware that I am immersed in an abundance of love. In the midst of pandemonium, my faith and spirituality were on trial. Is it genuine, or have I been playing some religious game? If my faith cannot stand the test of adversity, what good is it?

I am still trying to understand how I arrived here. But “Why?” is a pointless question to ask when suffering. Rather, one should ask, “Who can I depend on to walk me through this time?” As the writer Ram Dass has said, “We are all just walking each other home.” Who among my family and friends can I reach out to? Have I moved beyond religious belief to entrusting myself to Him in whom I believe?

Connecting through Stories

Within 48 hours, I began to feel comfortable enough in this unfamiliar environment to begin conversing with strangers. Sitting around a table during free time, I shared with a group of four young men my story of recovery from alcoholism, finishing on what I hoped was an inspirational note: “You guys have a lot of life yet to live. What if you turned those years to good by seeking and doing God’s will for your life? Just think of what may lie ahead for you.” They each nodded, and I silently sent up a prayer.

As we walked out of the room, I saw an old man sitting on the floor against a wall, his mouth swollen, bleeding from head and face, with two medics passively standing over him. Later that afternoon, a middle-aged man two cells down from me would not get up when called. He lay unresponsive. The inmates shouted for medical help, yet no one came for at least five minutes. Orderlies radioed for a stretcher, which took another ten minutes. Finally, they carried him off. I never saw him again. I don’t know if he lived or died.

One afternoon during our lockdown, I thought I heard someone calling me. I noticed a speaker in the corner of my cell, but when I stepped close, I knew the sound wasn’t coming from it. I listened intently to the voice. “Hey, Ol’ Timer! Look at your wall!” I looked toward the sound and saw a drinking straw moving back and forth through a hole in my wall. It was my friend in the cell next to me. “Hey, talk to me, Ol’ Timer. I need to know that you’re OK!” I laughed and said, “Yeah, I’m OK.” “That’s good,” he replied. “Stay strong in there. You’ll get out of here.”

Pilgrim’s End

It was standard procedure at Clayton County Jail to move inmates who couldn’t make bail up to the general population by day five. My friend told me I did not want to get moved to the general population. That is another level of human degradation, violence, and risk, he said.

It was day four. The gears in jail move slowly if they move at all. Nothing is sure here; nothing can be counted on, and the clock to move me to general was ticking loudly. All I could do was wait.

An hour before the group of us would move up to general, a guard came to my cell and said, “Toohey—you’re getting out! Grab your s**t and follow me.” Two hours later I walked out of the jail to meet my two daughters waiting to drive me home. As we hugged and I got in the car, I felt more like an inmate being transported somewhere else than a father. If this environment could have such a drastic effect on my condition after only four days, what does it do to those incarcerated for months, or years?

While my wife was walking the Via Dolorosa in Old Jerusalem—the path Jesus walked to his execution—I was walking my own Via Dolorosa, the path of the imprisoned, with similar jeers, torments, terrors, sadness, and the occasional cruelty. Yet the road to Calvary and all its suffering also led to the road to Emmaus, where Christ used his life experience to bring hope and courage to others. In those four days, I experienced the joy that comes from being led through darkness and deprivation toward a purpose and usefulness in a way I would never have chosen for myself.

Three months after my release, my case was dismissed. In the words of the Alabama district attorney: “The State lacks sufficient evidence to prosecute the offense as charged. Further prosecution of this case would not be in the best interest of the State or judicial economy.”

As my Jewish friends pray at the end of the Seder feast: “Next year in Jerusalem.” ♦

Bob Toohey is a a poet, essayist, and blogger at the website “Falling Forward.” He is a graduate with majors in both English and biology from the University of Alabama and a winner of the the “Write On the Sound” regional writing contest for both poetry and essay. His poetry has been selected for inclusion in several regional publications, including the WA 129 anthology. He is a member of the Alabama Writers Cooperative.

Bob,

Thanks for sharing!

From time to time I can image I’m prepared. I also suspect the test will come when I’m least expecting and ready for it. I’m glad you made it out the other side!

Love ya!

Stan

Hi brother, your post brought me to tears. Wow. I cannot imagine what you have gone through. Keep on writing – the Lord has something special in store for you to bring you through such circumstances – your life is a book yet to write – you are doing good to others.

One of the best memories I kept from our “world tour” nearly four years ago was the few minutes Jacqueline and I spent with you and Susan.

Much love and hugs

Love you, my friend. Visiting you and Jaqueline is on our bucket list!

Thank you for sharing a very painful and personal event and showing us what is truly important. Your are an inspiration to me.

Troy Whitehall

“A Pilgrimage in Parallel” by Bob Toohey offers a profound narrative that transcends the traditional pilgrimage story, weaving together themes of faith, redemption, and the unforeseen journeys life thrusts upon us. Toohey’s account of his arrest at the brink of a spiritual journey to Israel, juxtaposed with his past and the shock of facing a long-forgotten charge, is both gripping and deeply moving. This story highlights the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity and the power of love and forgiveness. The pilgrimage, although not the one initially envisioned, becomes a testament to the inner journey of understanding, growth, and the quest for peace within oneself. Toohey’s narrative is a compelling reminder that sometimes, the most significant pilgrimages are those that lead us through the depths of our own lives, challenging us to confront and overcome the obstacles of our past.

Thanks for the kind review.

Bob

Love and Prayers and Appreciation continue for You and Susan. Please keep on writing, Good Neighbor. You continue to Bless our lives here in this community.

Thank You.