Reintegrations by Douglas C. MacLeod Jr.

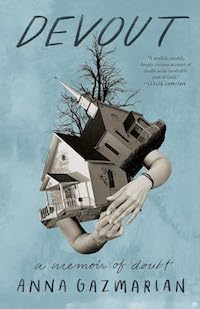

Devout: A Memoir of Doubt

By Anna Gazmarian

Simon & Schuster, 2024

$27.99 192 pp.

Anna Gazmarian suffers from bipolar disorder. She was first diagnosed in 2011; she had lost her job, 20 pounds, and her will to stay in college, so she decided to get help. She had been taking Cymbalta, a medication with multiple side effects, but her depression and anxiety was getting worse. She envisioned committing suicide, even though she was taught that killing oneself is a sin; she is a Christian who embraces her faith, so much so that she sought out a Christian therapist to give her counseling.

Biblical counseling, as Gazmarian explains in her new memoir Devout, is when “a clinician uses the Bible to diagnose and interpret your mental and emotional states of being instead of integrating the basics of psychology, which is seen as secular.” As well-intentioned as this form of therapy is, it did not work for her. She knew she had to do something different, something less spiritual in nature, because her inner turmoil was just too intense for her to handle with prayer journals and Bible readings.

She called the Mood Treatment Center in Wiston-Salem, North Carolina, and found Dr. Ferguson, a secular therapist who used science rather than Scripture to help her through her darkest days. By employing science, observation, and faith, Dr. Ferguson diagnosed Gazmarian and opened up a whole new world to the ailing writer—who, in turn, is attempting in her memoir to help other devout Christians (and, arguably, others outside of her faith) who may be experiencing similar mental health challenges. Gazmarian succeeds in this mission. In a short amount of time, and for the sake of those with suicidal ideation, she makes sure to let them know that they are not alone, that help is out there, and that oftentimes faith can only take you so far.

Gazmarian also succeeds in her articulation of how religious communities can stigmatize, and trivialize, mental health disorders and physical challenges. Early on she writes: “Whenever anyone in my church died by suicide, struggled with addiction, or got pregnant before marriage, Satan was responsible . . . When responding to questions about why suffering existed, church leaders in my community tended to blame the pain in our lives on Satan or sin rather than admit that there were things that happened in this world that we had no logical explanation for.”

This pious denouncement and dismissal of mental health issues has two main implications for Gazmarian, one more obvious than the other. First, claiming Satan is behind a person’s struggles does not stop that person from being depressed or suicidal; and second, claiming that the way through these issues is to have faith and believe Jesus Christ will save that person gives them a false sense of security, which can lead to more doubt, fear, and confusion: Why is Jesus/God not saving me? What have I done to deserve this? Why does Satan have this hold on me?

Gazmarian attempts to answer these questions for herself. Even though she continues to be steadfast in her faith, it takes emotionally separating herself from the church to recognize that her disorder is a part of who she is. It needs to be embraced and treated, not necessarily by religious abstractions and lamentations but by therapy and the right combinations and dosages of medication.

Much of Devout goes back and forth between Gazmarian’s personal experiences and her understanding of biblical teachings, which shows she still has reverence for the quintessential tome. At times she equates her experience to that of biblical characters like Job, Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar, and Moses. “I connected to Job feeling the weight of everyone offering advice and counsel for why everything was going wrong in my life,” she writes. “The same seemed to be happening in mine. Many of my closest friends who knew that I had been struggling for months told me to be joyful, to pray more often, to look at the bright side, to count my blessings.” By empathizing with biblical characters, Gazmarian is able to see the context for her condition and recognize her history of emotional suppression. This, unfortunately, can be very dangerous for the patient going through the experience. Dr. Ferguson helps her see this while making sure that she receives the proper medication and counsel that she needs.

Throughout her journey to better mental health, Gazmarian has to face many obstacles: racing thoughts, obsessions, mood swings, sleepless nights, manic episodes, delusions, disconnectedness from family, changes in medication. She has to endure all of this while still trying to manage her everyday life. She goes back to college, tries to get involved with Christian clubs, and attempts to make friends, but ultimately discovers they are just as dismissive of her situation as many of the other Christians she’s encountered. Positive words and Scripture readings and discussions about the beauty of the afterlife do not help her, she says: “As someone fighting to stay alive and taking medications to prevent thoughts of death, I couldn’t take solace in the afterlife.”

The last sections of Devout have Gazmarian meeting her boyfriend (now husband), David, and a poetry professor, Dr. Glidsan—two people she is able to really connect with because they seem to be grounded in reality and understand that both constructive criticism and compassionate caring can help those deep in depression come out and engage with the world again. Dr. Glidsan sees her talent, which becomes a steppingstone to her earning an MFA in creative writing from Bennington Writing Seminars; and David sees her complexities and challenges as manageable, beautiful, and in need of recognition. Gazmarian speaks of David’s empathy as being both detrimental to him (he eventually has moments of depression himself, and needs medications to manage it) and lifesaving for her. But more so, it becomes evident to the reader that the two of them realize they were brought together by faith, hope, love, and the power of Jesus Christ.

Gazmarian speaks of several other people who helped her move on from what she calls “religious trauma,” professionally, emotionally, and spiritually, but the last one is the most important: Ezra, her baby girl. One gets the sense that even though Garmarian will continue to fight her inner battles, she understands her daughter was born as a gift from God, a “daily reminder of God’s goodness.” By the end of Devout, Gazmarian has embraced her identity, and it is quite clear that she would not have been able to do so without the help of the support system around her—including God, faith, and the doubt she held on to, much like Thomas before her. ♦

Dr. Douglas C. MacLeod Jr. is an associate professor of composition and communication at SUNY Cobleskill. He has written multiple book chapters, peer-reviewed journal articles, and book reviews throughout his almost 20-year career as an academic and teacher. Recently, he has had essays published in Childhood and Innocence in American Culture: Heartaches and Nightmares (Lexington Books); Holocaust vs. Popular Culture: Interrogating Incompatibility and Universalization (Routledge); and Film as an Expression of Spirituality: The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films (Cambridge Scholars Publishing). He lives in Upstate New York with his wife, Patty, and his dog, Cocoa Love.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!