“Real, Real Gone”: A Monk with a Passion for the Blues by Michael Ford

They say that if you don’t like the blues, you have a hole in your soul. From their African American roots, blues originated in the Deep South in the 1870s. The spirituals, work songs, field hollers, chants, and ballads all emanated from the newly acquired freedom of former slaves, reflecting all too often the racial discrimination they had faced.

Gerard Garrigan has long been drawn to this genre of music. As a Benedictine monk-poet in the American Midwest, he’s had the strains of jazz running through his veins all his life. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the subject of one of the most significant blues songs ever written, “The St. Louis Blues” by W. C. Handy.

St. Louis was also home to Scott Joplin, the influential ragtime composer; Ike Turner, whose “Rocket 88” is often acclaimed as the first rock ’n’ roll song; Chuck Berry, sometimes dubbed the “father of rock ’n’ roll”; and the brilliant jazz innovator, trumpeter Miles Davis.

“Our African American musical tradition in St. Louis is very deep indeed,” Gerard told me. “St. Louis is also the hometown of the poet T. S. Eliot; and, in the early 19th century, Trappist monks established a monastery in our area, a community that would eventually settle in Kentucky and become Gethsemani Abbey, where Thomas Merton lived. So jazz, poetry, and the monastic life all form part of the history of St. Louis. Perhaps this has something to do with the person I became.”

Fr. Gerard is a former prior of St. Louis Abbey in Creve Coeur, Missouri, where there are 28 monks. There, in addition to his many monastic duties, he writes poetry, sometimes in his cell where he can concentrate. He has published six collections. He usually listens to his jazz favorites in his car, but when he is in the monastery he uses headphones plugged into his laptop. “I don’t want to disturb the other monks,” he says, smiling.

Gerard’s mother, Isabelle, exposed him from a young age to all the musical genres emerging from the African American experience, and a friend from his schooldays, the jazz pianist Mike Sissin, introduced him to “so much fine music” and still accompanies him to performances of the St. Louis Symphony. But there may be another explanation for Gerard’s love of jazz: Monks are liminal people. They live on the edge of society, away from the norm, a life that is a distinct subculture within the broader mainstream culture. Likewise, historically, the African American culture that produced jazz and blues has also been a subculture, a liminal world on the margins of a larger, a predominantly white majority culture in the United States.

“Monks spend much time praying and meditating on the Psalms from the Hebrew Scriptures which chart the suffering of the Jewish people, this liminal group who were oppressed for so long by larger, more powerful, cultures,” Gerard explains. “Jazz and blues, coming out of the pain of the African American subculture, resonates for me as a monk who spends so much time praying and meditating on the pain of the Jewish people in their Psalms. I also feel the emotional power of the blues is truly universal. I can’t imagine how the blues would not profoundly touch any integrated human being.”

Gerard composed this “Jazz Psalm,” written as a tribute to the St. Louis Cotton Club Band of 1925:

Praise God in this unlikely place

Praise him with trombone

Praise him with low-down saxophone

O praise him with big bass drum

And banjo strummed on bended knee

Praise him with clarinet pulled apart

O praise the Lord with violin

And with that big old tuba

Praise him with soul

And as you praise him above all things

Don’t forget to make it swing

You gotta, gotta make it swing

Fr. Gerard was born in 1952. His father, Harold, was a postman, a simple, quiet, and “very pious” man who would get up early to study the works of G. K. Chesterton, Etienne Gilson, Jacques Maritain, Ronald Knox, and Hilaire Belloc; he would also faithfully pray his rosary every day. Gerard also remembers how he also had a copy of Louis Bouyer’s The Meaning of the Monastic Life. “I would think my father was the only one in our working-class neighborhood who owned such a work,” he recalls. “He would meditate on his spiritual reading as he walked his mail route. He was a contemplative living in the world. After he retired, he attended Mass every day.” The example of his father inspired him to write these lines:

Your sweat drenched shirt

At 6 o’clock meant

Just another day

Had I thought

To thank you

You would have wondered

Why

And in the morning

Long before the world awoke

You’d pray your beads

Full unaware

God loved you more

Than you could bear

Isabelle Garrigan, a Roman Catholic convert from the American Episcopal Church and a fervent Anglophile, was a teacher and gifted musician. Although a classically trained pianist, she preferred playing ragtime, the blues, and other American popular music. Her father’s parents had married in London in the mid-19th century. Her Lancastrian Jewish grandmother had sung in an English opera chorus, while her grandfather, an Oxford graduate from the Isle of Wight, had reviewed opera. Isabelle could play the piano before she went to kindergarten. She said that, when they were babies, she would carry Gerard and his three brothers and sing to them at the same time. “My mother would come alive when she played the piano,” says Gerard. “She could swing and she had soul before they even came up with the term. She had a very discriminating taste in popular music. Her love of music influenced me greatly. Without music, life would be unbearable for me.”

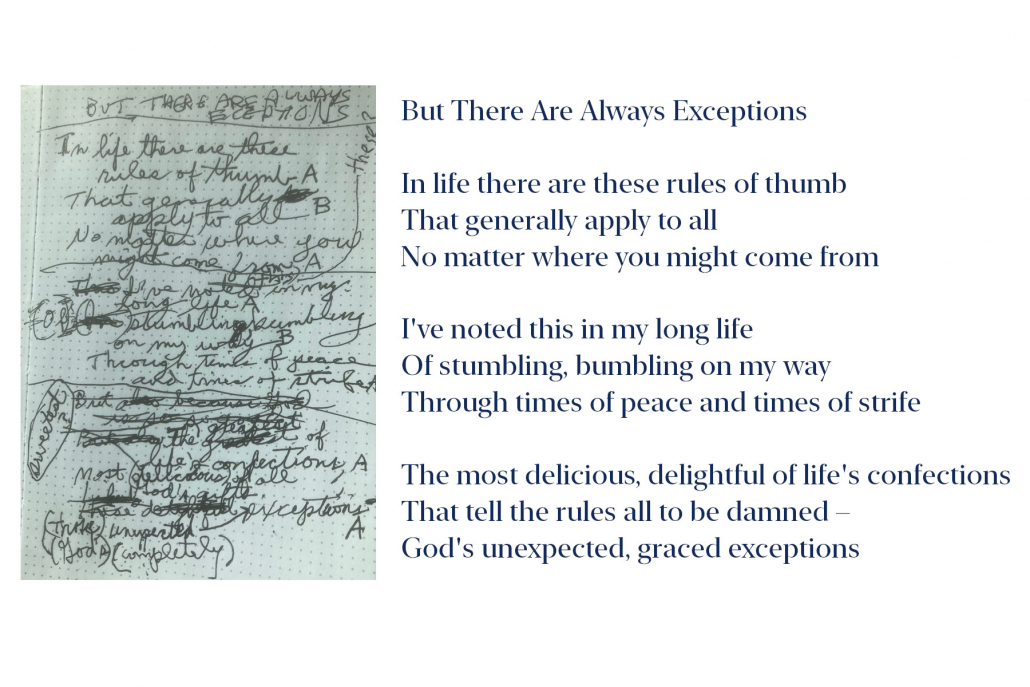

“I have yet to cease to wonder at the marvelous mystery of the genesis of a poem. So many times I have thought, while writing a poem, that it would go in a particular direction to find that the muse had other thoughts. The muse is nothing if not capricious, inscrutable and indomitable. This never ceases to fascinate and delight me. How the initial conception of a poem works out in all its particulars to arrive at the final version still confounds and mystifies me. Understanding how the mess of scribblings of the draft on the left came to birth in the finished version beside it is far beyond the tiny mind I was issued. Perhaps this is why I continue to write poetry.” — Fr. Gerard Garrigan

Gerard attributes his love of writing poetry to his Irish heritage. The tradition of poetic reverence—reverence for the word—is deeply ingrained in the Irish psyche and was probably passed down to him through the generations from his Irish ancestors who emigrated to the United States after the Great Famine (1845–1849). He also remembers his mother reciting poetry from memory. In high school he had an idiosyncratic English teacher from Ireland who would declaim Yeats to the class. “I would think he had something to do with putting the poetry bug in me,” he says.

The Benedictine monk admits, however, that he had not been a disciplined student. After studying English at university, he quit before sitting his degree and went instead to work as a roofer. Eventually he completed a two-year degree in library services, working in a public library and for the civil service before entering St. Louis Priory, now St. Louis Abbey, a 1950s foundation of Ampleforth Abbey in North Yorkshire, England. The Englishness of the monks intrigued him, and it was there, in fact, that he was first attracted to the contemplative life. The faith and temperament inherited from his father were also significant factors in Gerard’s discovery of his vocation.

Listen to Fr. Gerard Garrigan read his poem “But There Are Always Exceptions”

After working in the monastic school at St. Louis Priory, Gerard was sent to Chorley College in Lancashire, England, to study Italian, then moved to the Pontifical Beda College in Rome to study for the priesthood, living at Sant’ Anselmo, the International Benedictine College. He later gained pastoral experience in one of Ampleforth’s Lancashire parishes. Feeling at home in Lancashire, he grew to love Lancashire people, perhaps because of the Lancastrian stock on his mother’s side. He made his solemn monastic profession in 1984 and five years later was ordained deacon by Cardinal Basil Hume, who was the Abbot of Ampleforth at the time St. Louis Abbey was granted its independence.

“As monks, we are afforded the great gift of wasting long periods of time with God in prayer, both in common liturgical prayer and in private prayer,” Gerard explained. “We spend so much of our day meditating on God’s Word. And, of course, we believe our Lord to be the eternal Word. I think that the monastic milieu of silence, of meditating on the word, on meditating on the Word, is conducive to the writing of poetry. Thomas Merton is a prime example of a monk whose contemplative life bore much fruit through his output of poetry. If poetry is, as Wordsworth claimed, ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity,’ it does not seem surprising that a monk of an artistic disposition, who is afforded the gift of the tranquillity of a contemplative life, would write poetry.”

The famous line of the English poet and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins—“The world is charged with the grandeur of God”—makes the point that the things of this world, the profane, are actually sacred because all creation bears the imprint of the Creator. Gerard points out that God’s presence, glory, and wonder could be found not only in the Eucharist but also in what is commonly understood as the “profane”: in a jazz piece by Miles Davis, in a game of basketball, on a lonely road in Ireland, in “flawed and improbable creatures as ourselves.” He continues: “St. Benedict realized that the author of creation was present in the things of this world. This was why he insisted in his Rule that even the tools of the monastery should be treated with as great care and respect as one would treat the sacred vessels of the altar. My poems, therefore, manifest the hand of God, not only in what we would deem sacred, but also in the profane, the mundane, for, as the French author Georges Bernanos noted, ‘Grace is everywhere.’”

Davis (1926–1991) remains one of the most influential figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. During the 1950s, he famously started using a mute on his trumpet which became part of his signature sound. Gerard penned this tribute to him:

You had that sound

And you knew

You had that sound

And so you did not fear

To explore the universe and

Beyond

Notes soaring from your plaintive horn

To where your spirit

Longed to go

Where your spirit now

Has gone

And if I might impose on you

One request from one kindred soul

Take me with you to that place

Where you are real real gone.

“To the end of his life, Miles Davis remained an explorer,” says Gerard. “In his music he never ceased ‘to explore the universe and beyond.’ All great jazz, all great poetry, takes on that transcendent journey out of this existence and its limiting concerns to the transcendent world of heaven where God waits to embrace us. Like Miles Davis, we monks long to go where he ‘is real, real gone.’” ♦

Michael Ford may be contacted at hermitagewithin@gmail.com. Collections of Fr. Gerard Garrigan’s poetry may be obtained by emailing him at frgerard@priory.org.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!