The Man Who Turned Marginalization into a Mission by Mária Dominika Vanková

I wasn’t alive in the post-communist revolutionary early 1990s in Slovakia, yet there is an image of the time I carry based on the countless stories I have heard and read. In my mind, I see a grey day, a couple of colorful leaves lying scattered on the ground, and a Catholic priest sitting on a bench holding a homeless man’s hand. Comforting the man with his powerful gift of words, he gives him the hope that they are both dearly loved by God and can eventually find a home.

The Catholic priest was a Salesian, Fr. Anton Srholec, born in June 1929 into a family of agricultural workers in the western Slovakian town of Skalica, known for its distinct bakery. Already during his childhood, his parents recognized his extraordinary priestly potential. The entire family made big sacrifices so that in his early teens he could afford to start studies with the Salesian Order in Šaštín, a town with rich Catholic tradition, particularly in Mariology.

However, his dream to become a priest came to a quick halt when communists took over the country in 1948. In Šaštín, one of his teachers was Bl. Titus Zeman who, during those trying times, put his life on the line for his young students. He organized an escape over the River Morava, so the students could finish their theology studies in Turin, Italy. It was an especially dangerous move because at the time the borders were guarded by the Communist army, ready to shoot their own citizens who would make any effort to break free from the regime.

Unfortunately, on a fateful day in April 1951, the river’s stream was much more flooded than usual for that time of the year. As a result, the group turned back, upon which they were all caught by the Communist army. Srholec was only 21 when he was convicted for his priestly aspirations as “a traitor to the Communist nation” and sentenced to manual labor in a concentration camp in the Jáchymov uranium mines in the Czech Republic. There, on a daily basis, he suffered cold and hunger and was exposed to highly toxic radiation from the uranium he had to work on.

Yet, as he describes in his book Light from the Depths of Jáchymov Concentration Camps (1996), in the camps they lived the values of the Second Vatican Council before it was generally approved by the church. They didn’t have any priestly clothes, big cathedrals, or strong homilies, but they found God in mutual friendship, help, secret peace prayers, and dreams of experiencing freedom again. All that mattered in those inhospitable conditions were genuine humanity and authentic faith in God.

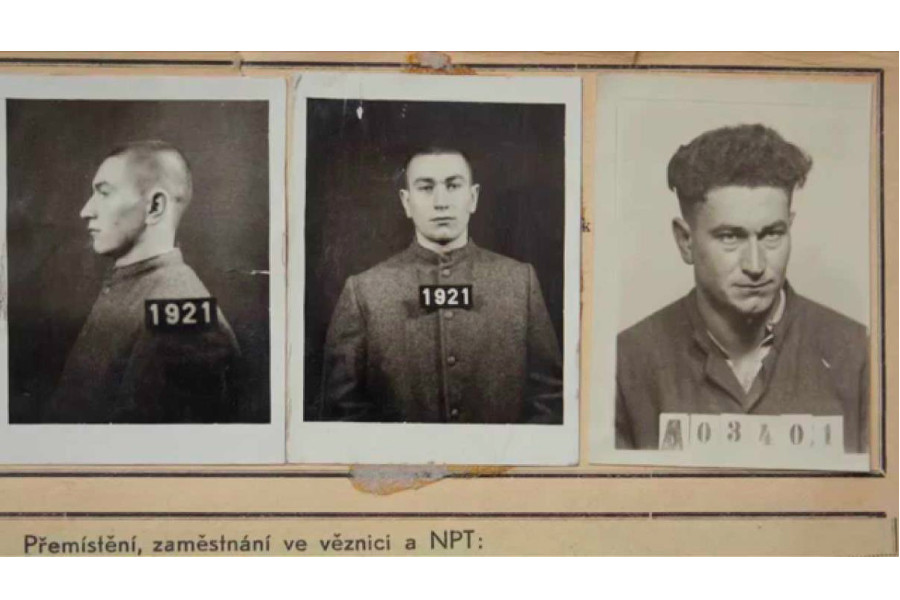

Anton Srholec’s prison photographs.

Source: Anton Srholec Documentary (2015) / Alena Čermáková

During those years, many political prisoners were shot, tortured, or died as a consequence of harsh conditions, including the leader of their group, Bl. Titus Zeman. After 10 years of hard labor with poisonous uranium, Fr. Anton was a rare survivor, miraculously with no immediate impacts on his health. But his ordeal was far from over.

Even after he joyfully returned to his family, he was closely followed as a “suspect with priestly aspirations” by the Communist secret police and agents who were trying to cause him any trouble they could. However, Srholec’s call was unceasing; he later described it as “something pressuring him inside.” Eventually, he made the decision to leave for a manual labor job in the Czech Republic in the hope that he would be able to shake the Communist spies. Although he was still observed in this new location, doing hard manual labor and spending time with simple workers taught him that “sweet priestly talk” doesn’t impress common people who, instead, desire honest discussions about faith.

A ray of sunshine finally appeared when, in 1968, “Socialism with a Human Face,” a liberation movement led by Alexander Dubček, took off. Srholec was able to legally cross borders to study theology in Italy, but because of the return of “old-fashioned Communist normalization” his studies were cut short, and Pope Paul VI quickly ordained him as a priest in 1970 in Rome. Afterward, to the shock of many, he returned via already closed borders to the revived strict Communist regime. For the rest of his life, he recounted this time in the language of human connection: “What sort of inner force it is that pushes you back to the danger you had escaped just to be close to your loved ones.”

Fr. Srholec served as a priest at one of his many small parishes in Western Slovakia, where he particularly encouraged Roma children from poor families to become altar servers.

Year: 1984 Source: The Foundation of Anton Srholec / Ivona Orešková

In the life story of Anton Srholec, nothing was ever easy, and neither was his priestly journey. Because of what he had been through, he learned to connect with people on a very deep level, and his homilies spread far and wide. The Communists didn’t take long to fight back, and they kept transferring him and giving him smaller and smaller parishes in the most forgotten corners of Western Slovakia. The final straw, however, was the famous Velehrad mass protest of Catholics in 1985. When the various regime-friendly figures were booed and taunted with chants of “We want the pope, we want the pope,” they turned off the electricity so no microphones would function. But nothing could stop Fr. Anton, who, despite his already difficult fate, was full of light. He came with an amplifier and candle and began to host the protest with prayers and songs dedicated to God as the darkness of the night was falling. In the end, all the people stayed, lit their candles, and kept awake the whole night. The night was filled with peace and hope. The punishment from the Communists, once again, didn’t take long: he was denied his state priest license, which was necessary at the time, and was therefore banned as a priest.

When the Communist regime collapsed in 1989, Fr. Anton was 60 years old. The moment was finally here, yet the persecution remained. It had only “changed its coat.” The Catholic Church was at its peak popularity at the time, which attracted many career-oriented individuals who used to secretly work as agents for Communist police against the church and/or had criminal ties. These people used their former connections to climb up to the highest positions in the church. Fr. Anton openly criticized the operations of certain shady characters and leaders of the post-Communist Catholic Church in Slovakia, which he saw as the highest disrespect towards Jesus’s gospel and church. As a consequence, he was banned as a priest—again. Once more, he was denied the ability to minister to any parish in the entire country, but this time, by his own church, the church he saw as a home and dearly loved—so dearly that as a young man, he risked his own life on its behalf.

Between these lines, I see the image of Fr. Anton holding the homeless man’s hand. I can only imagine how he felt the deepest pain of that homeless man’s hurt heart. But what I can’t picture is the pain he had to feel from his constant marginalization, even in his own church, after which most people would fall into deep depression and paralysis. Yet he didn’t lose faith in God and the church and made marginalization his mission.

Since communism didn’t permit unemployment (as a matter of fact, under communist policies, unemployment was a crime that could result in a prison sentence), there was a steep climb of homeless people due to economic changes after 1989. These people were strongly marginalized in society, and Fr. Anton not only connected with them on a personal level but also actively responded by establishing one of the first institutions in Slovakia for the homeless, called Resoty, in 1991. He worked hard on the project together with his good friend and erstwhile supporter Rita Carberry, a religious sister of the Presentation Sisters from Ireland. With great love, he decided to devote all his remaining life to the homeless.

Fr. Srholec attentively listens to a homeless man at Resoty, 2014. Source: Matúš Zajac

Although the church in Slovakia had done its damage, and people were staying away from Fr. Anton, internationally he became increasingly noticed. In 1992, US president Bill Clinton invited Fr. Srholec for a prayer breakfast, and in 1999 he received an award from Cardinal Franz König for his outstanding work for the Catholic Church. And since Fr. Anton was silenced, he received more and more encouragement to write his thoughts and homilies by his ever-growing circle of friends, many of them artists, scholars, politicians, and scientists inspired by his forward-thinking Christian thought. His writings took off, and his books were again and again sold out. It was just a matter of time before people began to ask how it was possible that this priest with so much inspiration to share, so full of light and the Holy Spirit, was prohibited from priestly service! It was reminiscent of what was written about Jesus in the Bible: “He taught as one who had authority, and not as their teachers of the law” (Matt 7:29, NIV). In 2003, Fr. Srholec was awarded a presidential award in Slovakia, with many other awards to follow in the next decade.

The exceptional public interest grew into exceptional media interest—after all, Fr. Anton always had a great answer for every concern. He would describe mercy with the words: “As for every illness there is an herb, so for every sin, there is forgiveness.” He encouraged people to have courage: “Never be scared of your enemies. The small ones are afraid of you, and the big ones can either kill you or multiply you—in both cases, they’ll do you a favor!” He saw Christianity through very active lenses: “Christianity is not anything we should discuss. Christianity is something we should live.” And he always understood that life and human responsibility go much deeper: “To live a meaningful life and to serve, one does not need high-ranked positions, or to be dressed in fancy clothes.”

Apart from working with the homeless, Fr. Srholec didn’t hesitate in other fields as well. He initiated a memorial for the victims of communism titled “The Gate of Freedom”; presided over the Confederation of Political Prisoners of Slovakia; greatly pioneered ecumenical and inter-faith dialogue in Slovakia, to the point that he was nicknamed the “Archbishop of Ecumenical Christianity”; and attended a well-recognized annual cultural and music festival in Trenčín called Pohoda (“the Chill Out”), where many young people would fill up the room to listen to him. As a believer of human rights and equality, he never understood, among many things, the prohibition of the ordination of women in the Catholic Church, and would repeat publicly: “Look at the Lutherans—they have women as priests, and not a single one of their churches has ever fallen down!”

Built in 2014, the Hermitage of Anton Srholec in Bioclimatic Park Drienová in north-central Slovakia, which also features the Library of Anton Srholec, hosts ecumenical and environmental events. Source: Earch.cz: The Architecture Magazine

After Fr. Anton Srholec passed away from cancer in January 2016, the entire country felt the heaviness of sadness. A journalist, Martin Krno, wrote a strong statement: “A priest without a parish but with a huge heart, an altruist who didn’t only talk about charity, lost his last battle yesterday. Anton Srholec was a publicist, a long-standing principled fighter for human rights. He managed to come to terms with a serious illness, but he never came to terms with injustice, unfreedom, inequality between people and nations.” The recognition of Fr. Anton—who, ironically, after his lifelong persecution and suffering, became the most beloved priest of Slovakia—didn’t stop after his death. Countless memorials were built, including the Foundation of Anton Srholec “António” and Hermitage of Anton Srholec, and an annual Prize of Freedom of Anton Srholec was established in his honor. He was elected by the general public as the third greatest Slovakian in history and most influential contemporary personality in 2019. An asteroid was named after him in 2021, and in 2022 the president of Slovakia, Zuzana Čaputová, paid him a special respect. Many cities have announced that they want to name a street after him.

Despite all his trials and tribulations, Fr. Anton Srholec lived a powerful life with a strong purpose that is now an uplifting story for all those who struggle. He proved that in the end, there is no need for prestige, high-ranking positions, or golden cross necklaces to achieve real greatness, but rather a genuine love for God, a humble heart, and friendship and kindness for all those who suffer. My good friend and former English teacher, Ľudmila Sabová, once described it beautifully: “Our António probably had to go through all those difficulties for they shaped him into a diamond. He was a lighthouse for us all, and even when they threw him out on the margins, he shined there much brighter than those, small in the spirit, who remained at the center.”

Today, the highly important church officials who once banned him are in intense disbelief. They stand in the shadow while the light of God is falling on the grave of Salesian Fr. Anton Srholec, whose legacy powerfully continues eight years after his death, to what would be his 95th birthday in June 2024. ♦

Mária Dominika Vanková is a writer from Slovakia. She has worked with peace-building and poverty alleviation initiatives in Southeast Asia, and is currently compiling archives of Fr. Richard McBrien’s syndicated columns on theology. She is the founder of the Club of Friendship Slovakia–Cambodia and a coordinator of humanitarian aid to Cambodia.

Further Resources

Chrappa, P. V. (2015). Bezdomovec z povolania (Homeless by Profession). Svätý Jur: Limerick.

Čermáková, A. (Director). (2015). Anton Srholec [Motion Picture].

Krno, M. (2016, January 7). Anton Srholec, kňaz a večný rebelant (Anton Srholec, a Priest and Eternal Rebel). Retrieved from Pravda: https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/379169-zomrel-knaz-anton-srholec/

Srholec, A. (1996). Light from the Depths of Jáchymov Concentration Camps. Prešov: Michal Vaško.

Srholec, A. (2014). Sviatočné pozdravy (Festive Greetings). Prague: Slovart.

The Foundation of Anton Srholec “António”. (2024). Životopis (Biography). Retrieved from Nadácia Antona Srholca “António” (The Foundation of Anton Srholec): http://antonsrholec.sk/zivot-a-dielo/zivotopis/

The Hermitage of Anton Srholec. (2022, 2023). Library of Anton Srholec. Retrieved from Bioklimatický Park Drienová (Bioclimatic Park Drienová): https://bioklimapark.com/aktivity/pustovna-antona-srholca/

The Institute of the Memory of the Nation. (2024). Anton Srholec (1929–2016). Retrieved from Ústav pamäti národa (The Institute of the Memory of the Nation): https://www.upn.gov.sk/sk/anton-srholec-1929/

Very moving story. What a great man, priest and just simple human. If only we had more like him.