Forster’s Personalism: Civic Healing and Howards End by Laura Hartigan

The stress of political engagement in the United States is high. Even neuroscientists are measuring the cortisol hormone level engendered by our current situation. (Cortisol is often referred to as the “stress hormone,” since it helps regulate our response to stress.) Contemporary articles have quoted the famed Yeats line about “how the center cannot hold”—including articles in the pages of this newspaper (Ed Burns, “Our Institutions Are Ourselves, August/September 2018).

The “center” identified here is the place of exchange of ideas and compromise between our political parties. This breakdown has many experts and pundits reaching for a reason to explain our increasing left/right divide, but few talk about how we will return to a civil, productive public discourse. No matter if the Democrats take back the presidency in 2020, the ugliness and polarization left in the wake of the Trump era will not magically dissipate. Like healing a fractured marriage, the work of reuniting in dialogue and trust with those of divergent worldviews will be daunting.

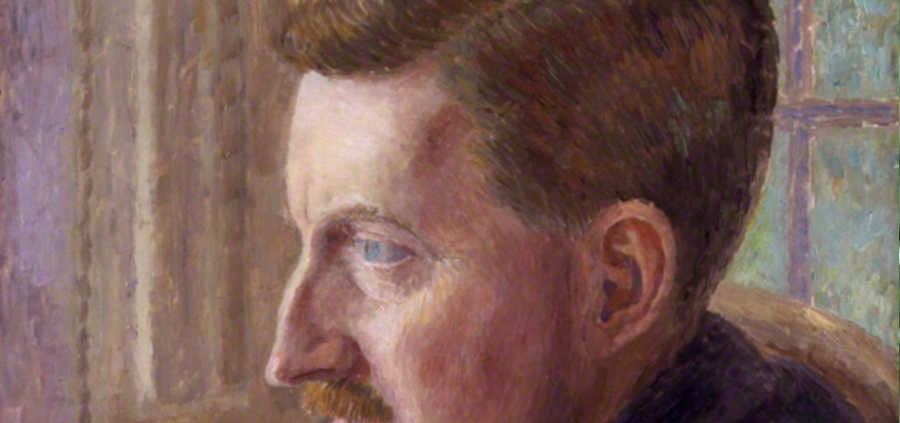

For inspiration in this regard, art is not just an escape, but a wise counselor for those searching for remedies. A recent STARZ production of Kenneth Lonergan’s screenplay of E. M. Forster’s novel Howards End, available for streaming since last spring, provides inspiration for those looking to establish civic healing. An award-winning screenwriter and playwright, Lonergan has skillfully streamlined the story while retaining much of Forster’s 1910 masterwork, including great portions of unedited dialogue. Smartly acted, with the typical appeal of a costume drama and augmented by a fast-paced narrative, it nonetheless retains the biting social critique of the modern world Forster intended.

Forster preternaturally addressed many of the stresses imposed on our society by modernity: the disorientation created by increasing technology, the exploited underclass left behind by the “big” economy, the variety of national identities and their conflicts, the desecration of the countryside (“Is this England or Suburbia?” he writes), and our subsequent loss of connection to nature and sense of home. Forster decried the loss of traditional customs that smoothed the relations between the classes, however imperfectly. He had true sympathy for the ill-treated Edwardian underclass but feared that the coming world would not provide anything better, and perhaps might do worse.

These startling changes, including the evolving roles of women, are all woven into a tale of who will inherit Howards End, an ancestral country home that literary critic Lionel Trillin has posited is symbolic of the question, “Who shall inherit England?” This is a question of obvious urgency in the wake of the Brexit vote and subsequent painful attempts to realize it, making Lonergan’s choice of Howard’s End as a follow-up to his acclaimed film Manchester by the Sea both laudable and topical.

The intersection of three families frames the interpersonal drama of the series. We are first introduced to the bohemian upper-middle-class Schlegels, composed of three twenty-something adult children: Margaret, the eldest, has raised her younger sister Helen and Oxford-educated brother Tibby after the early deaths of their parents. The sisters are similar in their commitment to art, culture, and social justice but have very different temperaments. Margaret is more integrated and equipoised, and Helen the more impulsive and romantic. (Their relationship calls to mind another of literature’s great sibling pairs, Dashwood sisters in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility.)

In contrast, the Wilcox family is an ascendant capitalist clan. As patriarch, Henry Wilcox seemingly cares not a whit about the sufferings of those who labor to support his expanding empire. His stiff upper lip masks emotions that even he is unaware of. Mr. Wilcox does, however, have enough sensitivity to marry Ruth Wilcox, the ethereal though passive mother whose family home is Howards End. Howards End is perhaps the central personality of the tale, one that the production lyrically invokes in the guise of an evaporating England of deep interconnectedness between nature and community. It is a place that, in Mrs. Wilcox’s understanding, deserves a “spiritual heir.”

Sadly, Henry and Ruth’s adult children are even more cravenly materialistic than their father and unlikely spiritual heirs. Charles, the eldest, awaits his ascension in his father’s business if his entitled ways don’t impede. Their daughter, Evie, awaits the catch of a wealthy husband—young or old, no matter, just wealth, please. The youngest, Paul, will soon leave for Nigeria to engage in a colonial enterprise that will likely exploit the natives. Through a chance meeting of the Schlegels and Wilcoxes while traveling in Germany, the families form a connection that results in the younger Schlegel daughter soon visiting Howards End. When a cloudburst of romance erupts between Helen and Paul—and ends just as suddenly—it portends a taste of the attraction/repulsion dynamic these two families will experience.

But it is both families’ interactions with the unfortunate Leonard Bast, a young clerk and his wife (the STARZ production updates her as a woman of color) living on the verge of a financial abyss, that exposes the divergence of the two families’ worldviews. As the story unfolds, the idealistic Schlegel women attempt to both economically rescue Mr. Bast and to disabuse the Wilcoxes of their sense of privilege. Realistically, Margaret and Helen experience both success and failures in these endeavors. More importantly, Forster’s text and Lonergan’s interpretation provide a roadmap of how to achieve the victories that do occur: a key to our reestablishing the center of compromise, dialogue, and civility in our society, a humanistic philosophy that values each individual.

Raised at Howards End, Ruth Wilcox received the guiding light of her behavior from both her ancestral community as well as her Quaker upbringing. When there is a conflagration between the Wilcoxes and the Schlegels over the hastily discarded romance of Paul and Helen, Forster writes that Mrs. Wilcox “heard her ancestors say: ‘Separate those human beings who will hurt each other most. The rest can wait.’ So she did not ask questions. Still less did she pretend that nothing had happened, as a competent society hostess would have done.” Mrs. Wilcox knows that there is a higher law than social conventions. We need to intuit her humanism more from her actions in the screenplay, a difficulty that is only partially overcome by Lonergan, but still quite discernable.

So too does Margaret aim to interact sensitively with everyone she encounters, although without the guilelessness or passivity that Mrs. Wilcox demonstrates. With a critical mind that has explored her humanism, Margaret has only deepened it and made it more unshakable. Hers has also been inherited, but through instruction from her intellectual German father, whose example she recalls at all moments of stress. Margaret describes as the “whole of her sermon” as: “Only connect the prose and passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer.”

Forster’s directive “Only connect!” as expressed through Margaret is the heart of his tale: to connect reason and emotion, the material and the spiritual. Forster believed it was imperative that each person reconcile these twin forces within oneself in order to best respond to and connect with each man or woman one encounters. The danger otherwise is to fall into either callous disregard (Henry Wilcox) or hazardous impulsiveness (Helen Schlegel), both of which can prove disastrous to society’s most vulnerable members.

As Forster and Lonergan are most surely unaware, this philosophy brings to the forefront of the Catholic mind the theology of personalism. Originally promulgated in the modern era by the French philosopher Jacques Maritain, these ideas were brought to the United States by the French social activist and theologian Peter Maurin, and into wider currency through the writings and lifework of Maurin’s collaborator in the Catholic Worker movement Dorothy Day.

Personalism is a worldview that sees each person as irreplaceably unique, never as a means to an end. Personalism also endeavors to address the needs of the less fortunate, sharing in the trials and joys of their lives in a direct manner, so evident in the Catholic Worker movement. Maurin’s teachings also celebrate the small agricultural communities in which a family home like Howards End are embedded. But perhaps most like Forster’s directive, personalism clearly asserts the importance of the body and the spirit as present in each individual made in the imago Dei.

Unique to Forster’s vision, however, and of note to those engaged in the public square, Margaret also takes seriously the spiritual poverty that is evident in the Wilcoxes. This is a poverty Mother Teresa described as endemic in the West, and which she felt was worse than the material poverty she encountered on the streets of Calcutta. Margaret attempts to rescue whomever she can from such a self-centered understanding of the world. Though initially naive about the cost of that rescue, she has the forbearance that speaks of real spiritual maturity, demonstrating an admirable commitment when put to the test. This test requires Margaret’s ability to assert her beliefs and discover the limits of her charity, as well as bequeath forgiveness more than once.

Like Margaret, we as Americans are each called by our faith to find ways to reconcile with those who are caught in a strictly materialistic worldview while not abandoning our obligation to care for those who are most vulnerable to the tides of a changing society; and to find ways to reach out to those who, in their spiritual blindness, do not see their fellow human beings’ God-given worth. For the center to be regained and held, Margaret’s mature, sacrificial humanism is a good inspiration.

Although Forster himself had left the religion of his youth behind, he never fully relinquished the essentials. As the critic Michiko Kakutani has stated, “he had always suspected that something mysterious and perhaps unknowable lay beyond the range of human reason.” Forster’s deep commitment to reconciliation is masterfully displayed in Lonergan’s adaptation of Howards End. It is given life in a way that can help guide us in the task of healing our country, one person at a time.

Laura Hartigan studied history and journalism as an undergraduate and is currently earning a master’s of theology at Seton Hall University’s seminary. Her interests include theological themes in films, faith healing and herbalism, spiritual growth through pilgrimage, Catholic economic thought, and the role of Eastern Christian influences in Catholicism. She lives in Montclair, New Jersey, with her husband of 32 years, and has two adult children.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!