Our Political Problems Are Moral Problems by Gene Ciarlo

We may hear a word or phrase over and over again until it becomes a cliché. The more we hear it the less meaningful it becomes. For me, that pithy saying is “We must be in the world but not of the world.” I don’t want to be in the world of American politics and economics today because according to my religion they are immoral. Today the world is in a struggle between individualism extended into nationalism, and its opposite, globalization, humanity’s evolution into a greater unity. The nations of Europe have opened up to immigrants primarily because of the outreach and openness created by the union of European countries. The United States is dragged into that scene kicking and screaming because we are so intent upon our own exclusiveness and exceptionalism. This tension has played havoc with our idea of self as a nation, our Christian values and those that Jesus would hold sacred, values that he taught and lived.

Look at the dominant values of our society today. They are the antithesis of anything that Jesus lived, preached, and taught by word and example in his few years—or maybe one year—of ministry. Global politics in general, but especially our American society, are in love with power and wealth, prestige and competition. For Americans, achievement means a good academic background, strong in the fields that will bring in financial prosperity as soon as possible on life’s journey. Individualism, “I” as opposed to “we,” stands tall in our list of values. It’s about me, even though American generosity may be outstanding when it comes to charitable causes. It is still a “me first” society.

Jesus was about us, not about me. In our trickle-down economic system, our society at large is not interested in social programs like universal healthcare, free education, or huddled masses yearning to breathe free. Conservative folks are more than a bit upset over welfare programs that consume our tax dollars, dollars we have worked so hard to acquire, they say. Tough it out and go it alone are the hallmarks of “real” Americans: so goes the conservative nationalist anthem. Those are the qualities that have made America great in the past and so it will be in the future. Perhaps that was an important attitude to possess during the hunter-gatherer times and on into the agricultural and industrial eras of societal development. But we begin to see and to change very, very slowly, because we are creatures of habit and hate to alter our ways or visit new possibilities.

Politics and so-called evangelism have become strange bedfellows in our time. Evangelism means gospel values, but popular theology has warped the truth into some sort of Christian nationalism, as if God is on our side. We decry Muslim extremism, and the truth about Islam fights mightily to tell us that radical Islam has nothing to do with the teachings of the Koran. The so-called evangelicals in our country readily endorse the deep-seated individualistic values that characterize our American society today. These values, in fact, totally contradict the values of Jesus, his lifestyle, his ministry, his life and legacy.

Here we are on the threshold of the Lenten season of 2019 in the Christian world. What do Christians do to pay attention to Lent that makes it specific to the historical moment? Make it a habit to go to church during the week? Observe some kind of penance or a fast? Maybe some of us will make it a point to read Scripture. Doing something positive might be better, like giving to a favorite charity. Sorry. None of these responds to the radical ways in which Lent ought to be lived in this historical time, when the conventional wisdom regarding value and worth requires radical reappraisal and action.

Lent today ought to be a time when we mix politics and religion. Yes, I say emphatically because our day and age is offering political solutions to moral problems. We must review the dominant values of our American society, the milieu in which we live, and recognize that we are not on the road that allows us to encounter the Christ among us. By and large, even among the faithful, we cannot count ourselves as Jesus people. We are not even church people, since Christianity itself has capitulated unawares to the values of our society. By our vote, we the people have spoken and have chosen Christian nationalism and American supremacy. It is a religion that Jesus would not recognize.

For too long we Catholics have been hung up on a caricature of Jesus as our Savior and Redeemer who died for our sins and saved us from eternal damnation. Christianity has been and still is reduced to redemption and salvation, sin and grace, heaven or hell, the main themes of the Catholic catechism. The sacrament of confirmation was about making soldiers of Jesus Christ, young men and women who would stand up for the teachings of—of whom or of what? They would stand up for the teachings of the church and its huge catalog of doctrines, rules, rituals, and regulations. This is not what Jesus was about. The way of the Anointed One of God began to be corrupted as far back as the fourth century. I honestly believe that Jesus would not be pleased with what Christians today accept as his way of life, his philosophy and lifestyle. We call it Christianity, but it is more manmade than inspired by God-in-Jesus.

We have politicized moral crises like welcoming immigrants and those seeking political asylum, accepting the poor and downtrodden, the homeless and the refugee. In our political scenario they are outcasts, murderers and thieves who are imposing upon and corrupting our national values, values that have made us unique and have given us national identity as British or American, French, Italian, German or Hungarian.

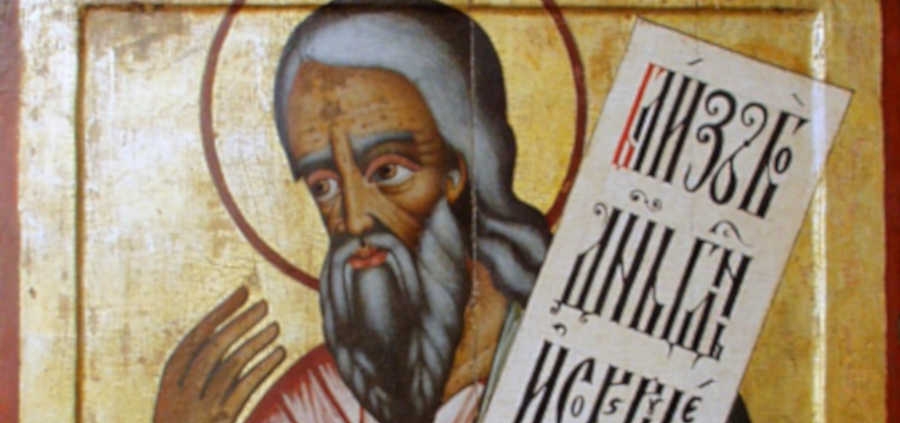

Marcus Borg, eminent scripture scholar, cites the prophet Amos, who in his visions and warnings most resembles the mind and spirit of Jesus. If there is one outstanding quality that characterized Jesus’s short but effective ministry, it was compassion: compassion for the poor and the suffering, the outcast and the unwanted, the shunned and those considered less than human. “Therefore because you trample upon the poor and take from him extractions of wheat . . . I know how many are your transgressions, and how great are your sins, you who afflict the righteous, who take a bribe, and turn aside the needy at the gate” (chapter 5). And in chapter 8: “Hear this, you who trample upon the needy and bring the poor of the land to an end, saying, ‘When will the new moon be over, that we may sell grain? And the sabbath, that we may offer wheat for sale, that we may make the ephah small and the shekel great, and deal deceitfully with false balances.’”

The rich get richer and the poor, poorer. It echoes so much the 1 percent in our own democratic, oligarchic, righteous American society. Read Amos for Lent as a good reminder of where we stand in our economic and political systems.

We are living in an age of practical atheism. From my perspective, present-day Christian religious beliefs and practices, by and large, are hanging on from a previous age that has museum value, albeit rightfully recognized as one of the principle building blocks of our modern society. However, the ecclesiology of the past is no longer useful, utilitarian, or of living value in our day and age. It is a showpiece of our world history. It gets dusted off now and then and dragged out periodically when it is necessary to recall what we’ve done over the ages. But let me not ignore the fact that there are small intentional communities of people who try to live by the example of Jesus, the spirit-filled man, that charismatic person who changed the course of history forever.

Is there hope? Are they our hope? In truth, my words are negative and pessimistic. I would like to live in hope and conclude on a positive note, and there is one. Pope Francis has said that in this day and age, unless Christians are revolutionaries, they are not Christian. Revolutionaries have always been a minority group of troublemakers. They have succeeded to win their cause time and again, even in the course of American history as well as world history. Christians after the mind and heart of Jesus need to be in the vanguard of the revolution that is bound to come, the peaceable revolution that Jesus started over two thousand years ago. The Christian world today needs troublemakers.

Gene Ciarlo is a priest resigned from active ministry in the Archdiocese of Hartford, Connecticut. He received an MA in Theological Studies from the University of Louvain, Belgium, and an MA in Liturgical Studies from the University of Notre Dame. After 10 years in the active ministry he returned to the American College in Louvain as Director of Liturgy and Homiletics. He now lives in peaceful and graceful Vermont.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!