All Creatures Great and Small by Jane M. Bailey

This summer we took our seven-year-old grandson to my sister’s cabin in Black Forest on the edge of Lake James in Marion, North Carolina. We hadn’t even gotten our suitcases unpacked when Rhys came bounding into the cabin. “Mema, do you have a jar? I just caught a frog.” I looked down at his outstretched arms and there, protected by his deeply cupped hands, was the tiniest frog you can imagine. It was so small you almost needed a microscope to see it.

“Hurry Mema!” he called.

I dug through the kitchen cabinets, found a Mason jar, and pounded some holes in the metal top. Off went Rhys, his frog safely, if not happily, in its new home. I called after him, “Don’t go past the teepee”—referring to a beautiful handmade wooden structure just inside the boundary of the forest within sight of the cabin.

Little Rhys followed my advice, but I could see through the window that he was eyeing the forest beyond, anxious to get his hands on whatever creepy-crawlies were in the forbidden land. As I walked out to the deck he cried, “Mema, come with me to the forest.” Off we went, net and bug jar in hand.

My eyes searched the landscape for something exciting to show him, one of the abundant deer, a snake, or perhaps a bear! As I looked up and away, he was busy down in the moss and ferns, rolling over dead trees to find life teeming within the decay. Every small creature became worthy of exclamation—“Look at this!” or “Shhh . . .”—as he tiptoed with his net that he gently swirled and used to capture a butterfly. It was as if little Rhys was answering Saint Francis’s invitation to “see nature as a magnificent book in which God speaks to us.”

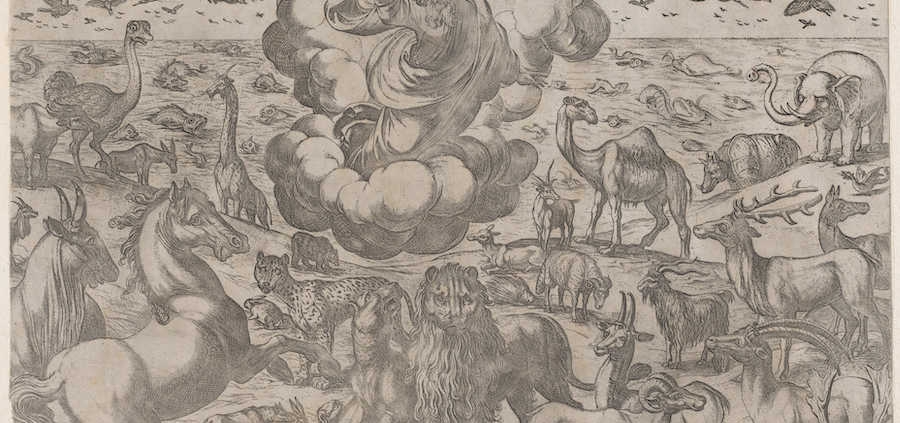

Rhys pointed out one camouflaged bug after another, careful to release his first prisoners while they were still alive before adding others. He wanted to catch and keep each of his creatures—but he wanted them alive. He seemed to feel God’s sustaining presence in every bug he caught. Watching him, the familiar children’s hymn echoed in my heart: “All things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small. / All things wise and wonderful, the Lord God made them all.”

Maybe if each of us took the time to see the world as a seven-year-old does, we too would feel God’s sustaining presence and respond to the call of books like Charles Camosy’s For Love of Animals: Christian Ethics, Consistent Action, which states that we have a serious obligation to respect and watch over creatures with care.

Rhys had found his own little world matched to his size to poke and prod. Somewhere else people are probing the worlds of outer space, unpacking secrets of the universe. As we quantify the real meaning of one hundred billion galaxies, Earth becomes a smaller part of the big picture. God has a huge house to maintain, and we are but a fleck of dust in that house. Within that fleck, we each have a brain with an estimated one hundred billion neurons—the same estimated number as there are galaxies. Great galaxies, infinitesimally small neurons, bugs on a forest floor: all part of God’s amazing world.

A U.S. Catholic article from June 19, 2008, also titled “All Creatures Great and Small,” shouts the marching order, “Let’s quit giving ourselves permission to wreak havoc on God’s good earth.” The article goes on to explain Thomas Aquinas’s view of nature as “God adorning the world with beauty.” Through nature, “we can come to discover God through the sacramentality of the beauty and the goodness of creation.”

Nearly 30 years ago, Rev. Michael J. Himes and Rev. Kenneth R. Himes, OFM, published a prophetic article in Commonweal magazine entitled “The Sacrament of Creation: Toward an Environmental Theology.” The authors argue that “[t]he first task before us, that which theology can assist, is to revision all beings as united in their createdness, given to one another as companions, sacraments of ‘the love that move the sun and other stars.’” They also remind us that “an environmental ethic must be informed by a careful analysis of the demands of economic justice.”

Creation embodies a lot more than just earthly creatures. Hidden in the weeds is the church, struggling to keep its place in a world pained by terrorism, guns, mental illness, hunger, poverty, disease, and climate change—all mind-numbing challenges to the human spirit. It can be hard to know where to begin to clean up our messes. We can’t simply go faithfully to Mass, say our prayers, and walk away. Small though we are, we are part of the great scheme of things. So what can we do?

Pope Francis answers this question in his daring May 2015 challenge to the church, the encyclical Laudato Si’. The encyclical charges us with the serious responsibility of setting international and local environmental policy. It also challenges us to adopt less consumption-driven lifestyles while reminding us that science is the best tool by which we can decipher the cries of the earth. Most important, Pope Francis attunes our conscience to the “care of our common home” with the pointed question, “What kind of world do we want to leave to those who come after us, to children who are now growing up?” (#160)

Other church leaders have spoken of the ecological crisis in the past, but none with quite the same urgency as Francis. In 1989 Pope John Paul II cited the ecological crisis as a moral issue and highlighted the ethical dimensions of environmental crises. The 1991 U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops statement Renewing the Earth: An Invitation to Reflection and Action on Environment in Light of Catholic Social Teaching addressed the protection of life and the dignity of the human person and stated “this task cannot be separated from the care and defense of all creation.” The document noted that “[w]e are not gods but stewards of the earth.”

The question is: are we acting as the stewards we are meant to be? Catholic priest and ecologist Thomas Berry urges religious reflection on ecological challenges. “The present is not a time for desperation but for hopeful activity,” he writes. I look at the stars in the sky and wring my hands. It’s true I can’t stop world hunger, but I can bring rice and tuna fish to the local food pantry. I can’t stop industrial pollution, but I can pick up empty bottles along the side of a road. I can’t stop global ecological devastation, but I can join the local trust to preserve land. It’s not what we can’t do; it’s what we can do and then do, that matters. In Berry’s words, “Renewal is a community project.”

God points me to a grandson who pulls me down into the forest carpet and teaches me to look for the small, the camouflaged, the hurt, the endangered life we trample with our blind eyes. I daresay, it was my grandson who found the gospel of creation in this microcosm of life. Send forth thy Spirit, Lord, and renew the face of the earth.

Jane M. Bailey is a writer from Litchfield, Connecticut. You can find more of her work at JaneMBailey.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!