Organizing Principles by Nicholas Hayes-Mota

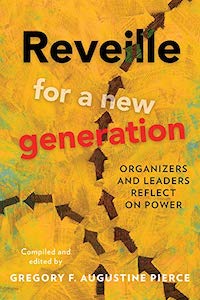

Reveille for a New Generation:

Reveille for a New Generation:

Organizers and Leaders Reflect on Power

Compiled and edited by Gregory F. Augustine Pierce

ACTA Publications, 2021

$19.95 432 pp.

This past spring, I taught Pope Francis’s latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, to a group of Boston College students for the first time. Their reactions were revealingly conflicted. Many agreed with the pope’s diagnosis that our contemporary world suffers from a serious lack of solidarity. They also agreed that without solidarity it will prove profoundly difficult to address any of the major challenges that confront us today, whether COVID-19, climate change, or racial and economic injustice. And they sympathized strongly with Francis’s call for “a better kind of politics, one truly at the service of the common good” (FT, § 154).

Yet many of the same students who found Francis’s political vision attractive also found it hopelessly idealistic. The pope may be right, they said, that a “better kind of politics” is what we most need to solve our problems. But is such a politics actually possible? And even if it were possible, how could it possibly be effective? In the “real world,” they wondered, don’t power and self-interest usually trump the common good?

Had I known of it at the time, I might have responded by sharing a few selections from Reveille for a New Generation: Organizers and Leaders Reflect on Power, a recently published community organizing anthology. For the kind of organizing it describes, in my view, embodies just the politics of the common good for which Pope Francis is calling. (At a recent gathering I attended for Catholics who organize, the pope himself agreed). It also shows how, by transforming self-interest and building collective “people power,” that politics can indeed be practically effective.

Reveille for a New Generation takes its title, and its inspiration, from Saul Alinsky’s 1946 classic, Reveille for Radicals. Alinsky (1909–1972), often called the “father of community organizing” (and equally often misunderstood), wrote the book to wake up his fellow Americans to both the challenges and the opportunities facing American democracy. World War II had just been won, and fascism defeated abroad, and yet, Alinsky warned, there were deep problems on the home front that could no longer be ignored. Though most Americans professed allegiance to democratic ideals, the majority of the American people were excluded—by racist laws, by poverty, by an anti-democratic political and economic elites—from actually practicing “self-government” in any meaningful sense. Democracy, “rule by the people,” was thus still far from a reality.

In response, Alinsky proposed an ambitious solution: a national movement of what he called “People’s Organizations,” local federations of religious congregations, labor unions, fraternal organizations, and other “people’s institutions.” Unlike the institutions of market or state, “people’s institutions” were effectively owned and controlled by their members and anchored in their cultural traditions, providing both the autonomous, already organized base of poor and working-class people and the moral foundation needed to build a grassroots democratic movement. Too often, however, ethnic, racial, religious, and ideological differences, frequently exacerbated by the divisive tactics of elites, prevented such institutions from working together. Alinsky’s genius was to propose drawing local groups of people’s institutions together, first around concrete, common problems and shared self-interests (better wages, better sanitation, safer streets, etc.), and then allowing them to progressively discover, through the very experience of collaborating to solve these problems, that they shared a common good and had the collective power to actualize it through solidarity. In the process, Alinsky added, they would not only become full-fledged participants in democracy; they would also discover their own agency, and dignity, as persons.

If this sounds rather like Catholic Social Teaching, American-style, you wouldn’t be the first to think so. Though Alinsky was raised Jewish and professed agnosticism throughout his adult life, many of his closest friends and collaborators were Catholics, from Monsignor John O’Grady, the legendary director of Catholic Charities, to Jacques Maritain, who tirelessly championed Alinsky’s work. (In fact, by Alinsky’s own admission, it was Maritain who prompted him to write Reveille for Radicals in the first place.) Likewise, in 1970, a group of Catholic bishops and priests inspired by Alinsky founded the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, which in its first several decades was the single largest funder of community organizing in the U.S.

Much has changed since Alinsky’s day, of course, not least within community organizing itself. In particular, the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) that Alinsky founded in 1940 has grown from a fragile, fledgling organization to become the largest network of “People’s Organizations” in the world, with over 60 local affiliates in the U.S. and abroad and a truly impressive track record of accomplishments. And whereas in Alinsky’s time the IAF was largely led by a small group of white men, today its leaders and constituents are men and women who cross nearly all the major lines of race, class, religion, and geography in the U.S.

It is this contemporary, and vibrantly diverse, IAF that finds a voice in Reveille for a New Generation, which is framed as an update to Alinsky’s original. And as befits today’s IAF, the new Reveille is the work of many authors rather than one. Lovingly compiled and edited by Gregory Augustine Pierce, it gathers together 52 short “stories, poems, sermons, eulogies and essays” about organizing, most of them by IAF leaders and organizers. (It is worth noting that, in IAF usage, “organizers” denotes the professional organizers formally employed by the IAF, while “leaders” denotes the volunteer leaders from member churches, synagogues, unions, etc. who comprise the bulk of the IAF’s leadership base.)

The variety of voices in Reveille for a New Generation is one of the book’s greatest strengths, but also its primary weakness. Unlike Alinsky’s original, the new Reveille does not present a single, coherent line of argument; it is more like a kaleidoscope of perspectives on organizing. Consequently, those readers not yet at least somewhat familiar with Alinsky-style organizing may find it confusing to navigate, and those looking to gain a first understanding of what organizing is and how it works may need to seek out other volumes to complement it (the first Reveille would be a good choice). That said, for those with the patience and/or the baseline of familiarity to explore it, Reveille for a New Generation is rich with insights of many kinds. One can learn much about the craft of organizing from it; one might learn about oneself, and God, too.

Reveille for a New Generation is divided into three major sections. The first section contains reflections by past figures who “represent the roots” of American organizing, which, as Pierce rightly observes, long predates Alinsky and the IAF. Famous fighters for social justice like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Mother Jones are included here, but so are lesser known figures like Ohiyesa (a Sioux doctor and writer) and Pauli Murray (an African American civil rights lawyer, feminist, and Episcopal priest). The second section (“Foundations of Organizing”) then shifts the focus specifically to IAF organizing, gathering together writings by or about the major leaders and organizers (starting with Alinsky) who built the IAF into what it is today; a particular highlight here are seven essays paying tribute to the late Christine Stephens (1940–2019), a beloved—and formidable!—Texas organizer who also happened to be a Sister of Divine Providence (one of the essays is appropriately entitled “Oh My God! She’s a Nun?”). The third section then looks toward the “Future of Organizing” and features writing by the rising generation of IAF leaders and organizers.

While the pieces in Reveille span many genres, most take the form of illustrative stories, which are a staple of IAF pedagogy and practice. Each piece, that is, exemplifies particular themes, lessons, or “universals” (core principles) of organizing (some admittedly better than others), and each likewise concludes with three “questions for discussion and reflection” thoughtfully crafted by Pierce to draw the former out. Many of these questions I found quite fruitful. They range from the philosophical (“What is the connection between our ‘politicalness’ and our humanity?”) and theological (“Are Power and Love Intertwined? How?”) to the personal (“Did you have an experience of personal injustice or powerlessness when you were growing up?”) and the strategic (“Why is it important for organizations to pick specific, immediate, and winnable issues . . . that people care enough about to act upon?”). Taken together, both the contributions and the questions in Reveille testify to the richness of IAF organizing as a tradition of reflective practice, one that many, including myself, have found personally as well as socially transformative.

Indeed, many of the authors in Reveille write quite movingly about how organizing has changed their lives. A number reflect, for example, on how organizing taught them to properly value their deep anger at injustice while also showing them how to channel it in constructive, rather than destructive, ways; for several, Sister Christine stands out as a model of “generous anger.” Contributors of diverse religious backgrounds—with a notably large contingent of Catholics—also speak to how their faith informs their organizing, and their organizing, in turn, their faith. A leader and organizer from my own IAF federation, the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (GBIO), even share an inspiring story about how “public prayer” transformed a challenging political situation in Massachusetts.

At the same time, many religious people initially experience a tension between their faith and certain aspects of community organizing, as may many Catholic readers of this book. As the late Rev. Jeffrey Krehbiel, a Presbyterian pastor, observes in one essay, “Jesus is understood by many church people to be a model of self-effacing humility and powerlessness, while community organizers and leaders exult in the virtue of self-interest [“rightly understood,” I would add] and the necessity of anger and power.” Likewise, community organizing invariably involves what Alinsky called “conflict tactics”: strategic, public confrontation of particular “targets” (such as government officials, business elites, and nonprofit executives) to hold them accountable to the larger common good and pressure them to act on its behalf. As I sometimes put it, while IAF organizing is a “politics of the common good,” it is also a form of “power politics.” And though the IAF attempts to reconcile the two, can they in fact be reconciled?

The stories told in Reveille for a New Generation, and still more the faithful people who tell them, offer good reasons to think that they can. By submitting themselves to the practical discipline of community organizing, these leaders and organizers have gained hard-won insights into what may well be the hardest question in political life. It is the very question my students were struggling with after reading Fratelli Tutti, and the question, indeed, that faces all of us inspired by Catholic Social Teaching: how can the moral and the pragmatic, the ethical and the effective, the “idealist” and the “realist” dimensions of politics be integrated? It is the great value of this book that it agitates readers to grapple seriously with that question, as its many contributors have done. You may not always agree with all they have to say. But you will come away much the richer for listening, and, just perhaps, a little more hopeful about politics. ♦

Nicholas Hayes-Mota is a PhD Candidate in Theological Ethics at Boston College. He holds a Master of Divinity from the Harvard Divinity School (2014), and an A.B. in Social Studies from Harvard College (2008).

Nicholas’s dissertation examines the possibility of a “politics of the common good” in contemporary liberal democracies. Arguing that prior theories of the common good have tended to understate the challenges posed to it by pluralism, power inequality, and inter-group conflict, he draws on the community organizing tradition of Saul Alinsky and the intellectual tradition of Catholic social thought to propose a new political ethic of the common good that is more adequate to these challenges. More broadly, Nicholas’s research engages the intersections of political, public, and liberation theologies; social and virtue ethics; and ecclesiology. His work has been published in Ecumenical Trends and the T&T Clark Handbook of Public Theology.

Nicholas’s scholarship is informed by his 10 years as a teacher and practitioner of faith-based community organizing, and his ministry in a variety of parish and university contexts. From 2015–2016, Nicholas was a Research and Teaching Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, where he worked with Marshall Ganz. While at Boston College, he has taught for two years in the PULSE Program for Service Learning. He presently serves as a trainer with the Leading Change Network (LCN), and a facilitator with the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (GBIO), the Boston affiliate of the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!