Difficult Conversations by John Marshall Lee

Today belief in the continued advocacy of white supremacy (what I will refer to as CAWS) informs the political posture of a number of Americans, though they may be unwilling or unable to admit it. Lost in the rush of rhetoric supporting patriotism, the American flag, and the principles of Founding Fathers is an honest assessment of the facts of American history: How have most folks with brown or black skin lived since coming to the colonies or, later, the states? Why are their stories different from my father’s (white) family’s experience of coming to Connecticut in 1926 from England? I ask myself why this is—why have I been exposed to such a slim American narrative? And, as I learn more as an adult, what can I do about it?

The Civil War ended in 1865, though the Emancipation Proclamation had been announced in 1863. But these events did little to modify community observances and local attitudes supportive of CAWS. More than 200 years of African American history record regulations that limited the rights of people of color in assembly, education, voting, and the exercise of activities enjoyed by others, including later immigrants.

On June 19, 1865, news of the Confederate surrender and earlier emancipation finally reached Texas. The date has been subsequently celebrated as Juneteenth. Yet even with the enshrinement of this holiday, the subject of how matrilineal, race-based chattel slavery created an inhuman reality for millions forcibly removed from Africa has not been adequately addressed. Nor has the way in which common literacy was denied to people of color and to their teachers by American laws.

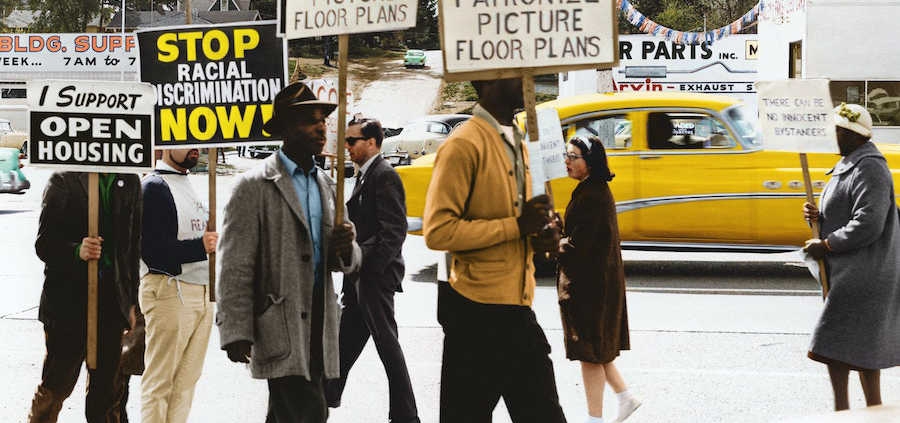

Bringing nominal equality of rights to former slaves was not a priority for most people in the North or South after the war. Thus, CAWS continued locally, with variations in the manner in which it had been applied before the war. Migrations of people of color to northern and western states were met with the spread of CAWS narratives in new communities.

The brief period of Reconstruction, supported by federal troops in Southern communities, did not last more than 10 to 12 years at most. Consequently, attitudes and temperament supporting CAWS made the enfranchisement of men of color in the South increasingly difficult. Women did not gain suffrage at all until 1920. The rise of hate groups like the KKK, the imposition black codes and Jim Crow, and extrajudicial lynchings and other barbaric practices that terrorized the black population persisted at least 90 years beyond the end of the Civil War. Yet large numbers of people of color had fought in the Civil War on the promise of freedom—a promise that, tragically, proved empty for most as it had in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 previously.

Currently, the attempt to demonize critical race theory (CRT), an academic topic not previously included in mainstream conversation, is one way that some reactionaries keep genuine and full American historical study and scholarship from view. An attack on CRT in the mainstream media is intended to hide the very real existence of broad-based CAWS in our country.

CAWS does not wish for a broader, fuller study of African American history, as it fears the changes that may flow from such knowledge. Facts that conflict with “comfortable” narratives are seen as inconvenient and to be avoided. Stories of bias and bigotry, filled with hatred, greed, and fear, predominate. An individual’s character and personal journey are seen as secondary to their skin color. No time is allotted for difficult conversations that maintain respect for the other. Isn’t that much simpler? And who has time for a difficult conversation, respectful of another American who might regularly attend faith services, vote, inform herself on issues, and serve when called upon, perhaps locally as well as in the military to defend our way of life?

If CAWS has enduring support, is it because the meanings of words like prejudice and racism are difficult to establish, define, and admit to ourselves and to each other? Has the principle of anti-racism been ineffectively communicated? Does our recent history indicate that the facts and beliefs of fellow citizens who support, either implicitly or explicitly, the continuation of white supremacy are firmly rooted? What is the case for CAWS that we allow it to maintain without creating space for conversations that challenge inappropriate, harmful, and erroneous beliefs? Where are the conversations in civic or religious settings, especially Christian ones, where people of all racial identities may gather as human beings, to attend to faith narratives and to seek truth together, to foster opportunities to lift everyone, be they family, friends, or neighbors?

If it is left unchallenged, the case for CAWS will continue to creep insidiously into our public life. It will prevent unity in our communities by sidelining those whose abilities, talents, and experiences are of practical and cultural relevance. We need to invite one another to sit around a common table, to speak and to listen and therefore to share in the power of our American experiment in democracy.

John Marshall Lee is a past contributor to Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!