Becoming All Flame by Frank Freeman

Burning Man: The Trials of D. H. Lawrence

Burning Man: The Trials of D. H. Lawrence

By Frances Wilson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021

$35.00 512 pp.

There aren’t too many books that you wish you had time to read again as you sit down to review them. But this was precisely my reaction to Burning Man, Frances Wilson’s new biography of D. H. Lawrence. This is partly because of the focus of the book, 10 years in the life of one of the most misunderstood authors of the 20th century, but also because of Wilson’s passion for and deep knowledge of her subject. What Wilson understands about Lawrence is that he was not a hedonistic, “free-love” sort of writer but a burningly religious one, which is why she prefaces her book with a passage from one of his letters:

I always feel as if I stood naked for the fire of Almighty God to go through me . . . One has to be so terribly religious to be an artist. I often think of my dear Saint Lawrence on his gridiron, when he said, “Turn me over, brothers, I am done enough on this side.”

Although it turns out that Saint Lawrence was more likely decapitated than roasted, the point is taken that Lawrence felt an artist should be a conduit of what he often called “the Holy Ghost,” by which he meant not the third person of the Trinity but a spiritual fire.

I have heard it said that Lawrence once referred to Dostoyevsky as the nastiest Christian you’d ever want to meet, though I have never been able to locate the passage. However, in a book of critical essays, Studies in Classic American Literature, Lawrence wrote that “out of a pattern of lies art weaves the truth,” adding, “Like Dostoevsky posing as a sort of Jesus, but most truthfully revealing himself all the while as a little horror.” When you read about Lawrence, you are tempted to apply the criticism to him. He is the nastiest bard of the élan vital you would ever want to meet. Of course, as usual, he has already admitted this:

The artist usually sets out—or used to—to point a moral and adorn a tale. The tale, however, points the other way, as a rule. Two blankly opposing morals, the artist’s and the tale’s. Never trust the artist. Trust the tale. The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.

How can one portray such a slippery eel?

“Everyone who knew him told tales about D. H. Lawrence, and D. H. Lawrence told tales about everyone he knew,” Wilson writes. She defines Burning Man as “a triptych of self-contained biographical tales which take as their subject three versions of Lawrence.” She focuses on the period between 1915 to 1925, a “decade of superhuman energy and productivity,” and divides it into “Inferno,” his time in England, “Purgatory,” his time in Italy, and “Paradise,” his time in America, mainly in New Mexico. Wilson sets herself the task of writing about Lawrence’s works that have been neglected in favor of his novels, namely his essays and poems; she wants to do the same with the people he knew and the roles they played in his life and he in theirs: “episodes and experiences that earlier biographers have passed over in a paragraph are here placed centre stage,” she says.

“Inferno” describes Lawrence’s life in England between 1915 and 1919. Lawrence’s father was a loud and boisterous coal miner, swarthy and strong and sometimes brutal, while his mother was beautiful, gentle, and artistic, but very much the martyr and intensely snobbish. She wanted her boys especially to “get on” in the world, didn’t want them to be boorish miners like their father. Part of Lawrence’s split nature was due to his parents’ unhappy marriage. It also didn’t help that his mother’s love for her sons was emotionally incestuous and that when Lawrence’s older brother, Ernest, died, D. H. (or “Bert,” as he was then known) became the focus of intense mother-love.

After his adolescent flame, Jessie Chambers, launched his literary career by sending his poetry to Ford Madox Hueffer (later to become Ford Madox Ford) at the English Review, and after he had eloped to Germany with Frieda Weekley, the wife of his former professor, Wilson states that Lawrence “structured his life—‘that piece of supreme art’, as he called it—around Dante’s great poem in the way that James Joyce shaped Ulysses around The Odyssey.” “This,” she proclaims, “was his primal plan, the complex figure in the Persian carpet that Lawrence’s biographers—because they have been looking from a flat perspective—have failed to see.” She supports this assertion by pointing out how each place Lawrence moved “was positioned at a higher spot than the last.” However—and I say this with regret because I wish it were true—she ultimately does not prove her thesis about Lawrence and Dante. But, as another reviewer has pointed out, she doesn’t really need to: in its myriad contradictions, Lawrence’s life is fascinating enough not to need this medieval scaffolding.

The central episode of “Purgatory,” the second part of the book which covers Lawrence’s time in Italy from 1919 through 1922, revolves around his haunting relationship with Maurice Magnus. Magnus was an American artistic fixer (he had been Isadora Duncan’s manager on a European tour) who was staying with the English expatriate writer Norman Douglas, an ebullient, immensely learned man and graceful writer who was also a pederast run out of many towns he was living in. Magnus was a debonair version of Uriah Heep: fussy and always well-dressed—Lawrence said he gave the impression of a fat pigeon always leaning forward—he was sometimes flush with money, at other times on the brink of living on the street. He was not above living beyond his means in opulent hotels, writing checks that would be sent back for insufficient funds, and then skipping out before he was caught.

Magnus also happened to be a Roman Catholic convert with a desire, at times, to be a monk. After leaving Douglas and Lawrence in Florence, he went to Rome and started writing bad checks until, running out of options, he retreated to Monte Cassino, the original monastery of the Benedictine order established by Saint Benedict himself. In February 1920, after exchanging correspondence, Lawrence visited Magnus there; the two went on an afternoon walk in the surrounding countryside, and though they had some vociferous disagreements, they also had a moment of a strange, almost spiritual, communion. “One can’t go back,” Lawrence pointedly told Magnus, who had a habit of taking refuge in the past, before blurting out that “Magnus would never be a monk.” Lawrence’s rebuke seemed to help Magnus face the truth about himself. Wilson writes:

Something had happened on the mountain top: he and Magnus had formed a Blutsbrüderschaft [blood brotherhood] of sorts. Lawrence never admits this, but it is the only explanation for what followed. Magnus put his hand on his friend’s arm and, rather than freeze with horror as he usually did when he was touched, Lawrence stopped mocking him and saw who he really was: He seemed to understand so much, round about the questions that trouble one deepest. But the quick of the question he never felt. He had no real middle, no real centre bit to him. Yet, round and round about all the questions, he was so intelligent and sensitive. Magnus, Lawrence’s guide, had reached into the pilgrim’s soul. They walked back slowly and in silence as the sun declined and the air filled with the cold of snow. Magnus kept close to Lawrence, “very close” and reassuring, “and I feeling as if my heart had once more broken: I don’t know why. And he feeling his fear of life that haunted him, and his fear of his own self and its consequences, that never left him for long.”

According to Wilson, Lawrence ascended to the closest thing to Paradise he would ever know in America—specifically, in New Mexico—between 1922 and 1925. Mabel Dodge Luhan, a wealthy American society lady who had married a Native American, Tony Luhan, and lived with him in Taos in what was called the Big House, wrote letters to Lawrence pleading with him to visit. Mabel dreamed of assembling a utopian community of writers and artists to live alongside the indigenous peoples of Taos, a vision that appealed to Lawrence.

Mabel could be a ruthless person, but she met her match in Lawrence and Frieda. Soon after their arrival, she and Frieda began to develop a friendship while Lawrence was out exploring. But whenever Lawrence returned to the Big House, the power struggles between the three of them began. Each one was jealous in some way of the other two. At one point Mabel and Lawrence were flirting while washing dishes; their fingers touched in the suds and Lawrence drew back. “There is something more important than love,” he said. When Mabel asked what this was, he grimly replied, “Fidelity.” Despite these dramatic scenes, Mabel found it within herself to gift Lawrence and Frieda a small ranch in the hills outside of Taos. They lived here until they returned to Europe in 1925. After stints in England and Italy, they eventually ended up in Vence, France, where Lawrence died in 1930.

Lawrence’s short life was a tangle of contradictions. He could be a very cruel man. When his friend Katherine Mansfield lay dying of tuberculosis (which Lawrence also had but would never admit until a doctor in New Mexico confirmed it), he wrote her a letter which included the scathing comment, “I loathe you . . . You revolt me stewing in your consumption.” His cruelty is only partially explained by an earlier letter in which he told Mansfield of a childhood friend who was dying of tuberculosis, adding, “on ne se meurt pas” (“One does not die”). Death revolted him as did consumption. He hated in others what he feared in himself.

Another cruelty comes in the essay “Memoir of Maurice Magnus.” One of Lawrence’s faults as a writer was that he never knew when to stop: he just keeps going and going, particularly in his essays, as if he is trying to wring the topic out of himself. In this essay, Lawrence reflects on Magnus’s taking advantage of people’s trust:

It is this betraying with a kiss which makes me still say: “He should have died sooner.” No, I would not help to keep him alive, not if I had to choose again. I would let him go over into death. He shall and should die, and so should all his sort: and so they will. . . . A little loving vampire!

The reader may grasp what Lawrence means about Magnus being vampirish and Judas-like, but does being a “scamp,” as Lawrence calls him elsewhere, really warrant death?

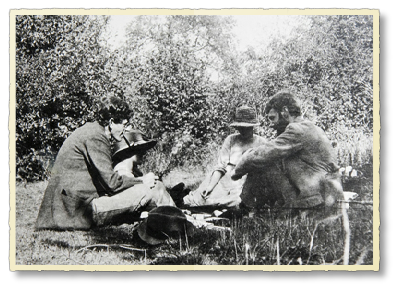

Bertie Farjeon, Rosalind Thornycroft, and Frieda and D. H. Lawrence in the woods behind Spring Cottage, Bucklebury, West Berkshire, 1919

As Wilson points out, sometimes Lawrence sounded like a communist, sometimes like a fascist. He did worship what he called “life” or the “dark gods”—or, one could say, nature—and taken to the extreme and with no moral framework to buttress it, this point of view can lead to the horrors of Nazism. Bertrand Russell famously said Lawrence’s ideas led directly to Auschwitz. And Lawrence did believe that some men were superior to others, and that the inferior should give way to the superior. I was very sad and angered to read that he advocated for euthanizing “the idiots and the hopeless sick and the true criminal,” which makes one wonder about the fate of a Maurice Magnus in a world run by D. H. Lawrence. At the same time, Wilson portrays Lawrence’s deeply utopian bent: he always wanted his friends of the moment to live with him communally and couldn’t understand—sometimes to comic effect—why no one ever took him up on his offer.

Another criticism leveled against him came from the feminist writer Kate Millett, who argued that his work led to an explosion of pornography and sexism in the ’60s. It is true that a would-be fascist or a would-be pornographer could find ways of taking Lawrence out of context to justify their beliefs, just as Nietzsche’s sister repurposed her famous brother’s philosophy to support the Nazi regime. However, Millett’s claim is problematized by Lawrence’s essay “Pornography and Obscenity,” wherein he says he would vigorously censor French postcard-type pornography. In this essay he also makes the same point Flannery O’Connor once did about the connection between sentimentality and pornography, both of which O’Connor said “cultivate immediate sensate experience for its own sake,” and criticized the disconnect between private lasciviousness and public propriety.

Despite their tumultuous marriage—they abused one another verbally and physically, often in front of visitors—it is worth pointing out that Lawrence was, as far as we know, unfaithful to Frieda only once, with Rosalind Baynes, known in her time as a great beauty. Wilson notes how many of Lawrence’s admirers have excoriated Frieda for her “mindlessness,” her sleeping with any man she fancied (before and after her marriage to Lawrence), her overall vulgarity. However, she did influence Lawrence tremendously, not so much in her ideas but in who she was as a person. She mocked Lawrence mercilessly for being the “great prophet,” she brought him down to earth, and she probably kept him from megalomania’s worst ravages. Although “[t]heir marriage was seen by others as a catastrophe,” Wilson writes, “this is not how Lawrence saw it.”

Marriage was his plot and his message to the world. “Your most vital necessity in this life,” he preached, “is that you shall love your wife completely and implicitly and in entire nakedness of body and spirit.” He believed in marriage not because it simplified sexual relationships but because it made sexual relationships more complex: marriage mattered because it was so damned hard. “I’m not coming to you now for rest,” he told Frieda when they ran away together in 1912, “but to start living. It’s a marriage, not a meeting . . . One is afraid to be born, I’m sure.”

Lawrence was not an easy man to live with. He strikes us as being as emotionally demanding as Van Gogh, but with something of the aura of sainthood. Not that Lawrence or Van Gogh were saints, per se, but that there is a certain kinship between them and the saints, many of whom are known for having prickly personalities. When she heard that Lawrence had run off with Frieda, Jesse Chambers’s response was, “At last I was really free.”

After Lawrence’s death and burial in France, Frieda and Angelino Ravagli, an Italian father of three with whom she had been having an affair, went together to live at the ranch in Taos. Soon, however, Frieda sent Angelino back to France to retrieve Lawrence’s body, have it cremated, and return with the ashes. There is some controversy over whether it was Lawrence’s ashes that made it back, or whether or not they were mixed into cement “used to make an altar stone” in a chapel dedicated to Lawrence in Taos; one particularly outrageous story says that Frieda, Mabel, and their English friend Dorothy Brett “sat down together and ate him.”

View from D. H. Lawrence Ranch, San Cristobal, New Mexico, looking toward Taos

Out of the restless wanderings of Lawrence’s life, Wilson has fashioned one of the most fascinating biographies I have ever read. Along the way she touches on many details I do not have the space to address here: details about Lawrence’s relationship with Katherine Mansfield and her husband John Middleton Murry; about Hilda Doolittle, aka H. D., the American poet who touched Lawrence when he wasn’t ready to be touched; about Tony Luhan and the native Pueblo community; about Lawrence’s critique of industrialized and mechanized society; about his religious and psychological views; about his acknowledgement that Christian monks had saved Western civilization.

Given some of the thornier aspects of Lawrence’s personality—the misogynistic streak that sometimes appears in his work, the questionable authoritarian tendencies hidden beneath the language of mysticism—Wilson necessarily defends her choice to write about him at all. Her reasons are that as a teenager she loved his novels, which he called “the one bright book of life,” that “his women were physically alive and emotionally complex,” that he saw himself “as right and the rest of us wrong.” Rereading him as an adult, she sees him as “composed of mysteries rather than certainties.” “He was a modernist,” she writes, “with an aching nostalgia for the past, a sexually repressed Priest of Love, a passionately religious non-believer, a critic of genius who invested in his own worst writing.” She adds that “Burning Man is a work of non-fiction which is also a work of imagination.” She is writing for us, as he did—it was really all he ever did—an account “of what it was like to be D. H. Lawrence.”

For those interested, two other books I read in conjunction with Burning Man help round out the portrait: Selected Poems of D. H. Lawrence, edited by Kenneth Rexroth, has a superb introduction; and The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays, edited by Geoff Dyer for NYRB Classics, gives a sound overview of Lawrence’s nonfiction. Dyer has also written a book about not writing a book about Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, that is worth seeking out.

The Bad Side of Books includes Rebecca West’s moving tribute to Lawrence, “Elegy,” in which she compares him with the holy fools of Russia and the fakirs of India, men always seeking holiness on the road. “Lawrence travelled, it seemed, to get a certain Apocalyptic vision of mankind that he registered again and again and again, always rising to a pitch of ecstatic agony,” she writes. Her conclusion to that essay, written to counter all the criticism heaped on Lawrence after his death, still speaks to any assessment of his life and work: “We must ourselves be grievously defeated if we do not regard the life of D. H. Lawrence as a spiritual victory.” ♦

Frank Freeman’s work has been published in America, Commonweal, Dublin Review of Books, and the Weekly Standard, among others. He lives in Maine with his wife and four children, dog, cat, and four chickens. He hopes to have his books published some fine day.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!