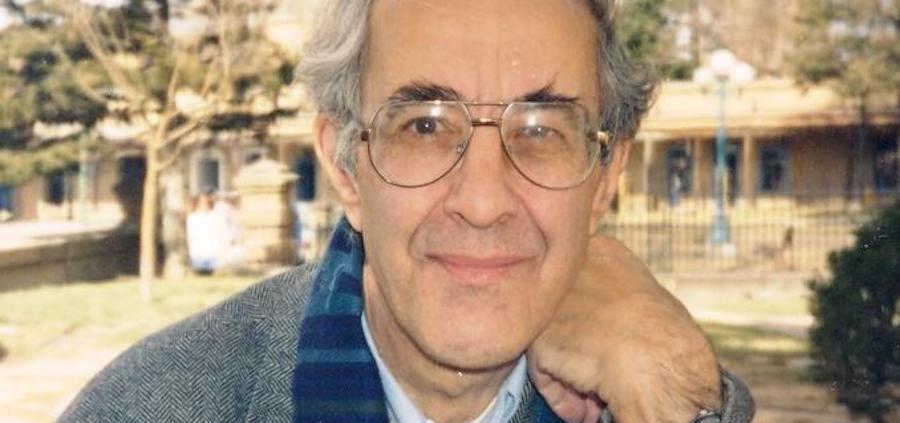

Like a Strong Wind: Memories of Henri Nouwen by Michael Harank

One February morning in 1983, while I was sitting in my room at Haley House, the Boston Catholic Worker community in the South End, I heard a rather loud knock at my door. I said, “Come in.” Henri Nouwen blew into my room like a strong winter wind. He introduced himself to me with a firm handshake—a signature of his powerful strength—and told me that Robert Ellsberg, a former editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper who was now a student at Harvard Divinity School, had told him about me. Henri explained that he had just left a tenured position at Yale Divinity School to accept a professorship at Harvard Divinity School. He needed an administrative assistant. Robert had told him that I had done some correspondence work for Dorothy Day in her last years.

I reminded Henri that I had met him a few years before when he came to the Catholic Worker community in New York to give a presentation at one of the “Friday night meetings” on the spirituality of his fellow countryman Vincent van Gogh. It was a splendid presentation, complete with brilliant slides, but unfortunately I had missed most of it because of hospitality duties—the “duty of delight” as Dorothy Day referred to them. Henri was a bit embarrassed that he did not remember, as he was noted for the intensity of his interest in meeting new people. But his embarrassment gave way to his more immediate interest in securing me to be his assistant at Harvard. Henri was a determined man.

Of course, I was honored to be asked by a man whose writings on ministry and hospitality had shaped my understanding of Christian service and compassion. His book The Wounded Healer influenced my awareness of the delicate balance inherent in any form of “service” to others that embodied a sense of horizontal solidarity with the poor, as distinct from the vertical “charity” of philanthropy. His writings pushed me to understand how my vocation of service among the homeless poor of New York and Boston involved challenging spiritual lessons taught by the apostles of the streets who were themselves “exacting spiritual masters.” The poor, addicted, and marginalized victims of predatory capitalism were often disguised Zen masters who carried sticks to whack the meditating disciples into a state of wakefulness and enlightenment—wakefulness to their sacred personhood made in the image and likeness of God, not the often cruel and insensitive labels assigned to them by racism, poverty, and class status.

While I was honored by his invitation, I was also cautious. Henri had a well-deserved reputation for expecting people to walk and even run the extra mile for him. I carefully explained to him that my primary work was to be part of the Boston Haley House community and its multitude of ministries to the poor and to the vocation of peacemaking in the world, especially around the issues of nuclear weapons and militarism. I said that I would like to work with him, but that I could only work part-time given my other community commitments. Henri was gracious in understanding my situation and laughed at my comments about his reputation. He explained that in the coming months he would be at L’Arche, in Trosly, France, at the invitation of Jean Vanier to do some writing and preparation for his teaching at Harvard in the spring semester of 1984. After an extended conversation, I was hired on the spot for 16 hours a week with a “just and living” wage—an important aspect of Catholic social teaching.

I would spend every week of the next six months in his office at the Divinity School, located in a tower close to the pantheon of divines who resided in the heavens (and even closer to the noted divines in their academic offices). Every week I made the subway sojourn from Copley Square to Harvard Square. I spent a considerable amount of time answering the telephone and responding to a voluminous stack of letters to Henri from friends, readers, and strangers. These letters ranged from personal friendships, requests for speaking engagements, and anguished pleas for counsel. Henri was gently adamant that each of these letters deserved a personal response from him. There were no idle hands in that office! I also spoke on the phone with Henri in France several times each week, consulting with him about the multitude of requests from his friends and readers. He attended to each of them with a sense of dedication and responsibility.

Henri was truly a pleasure to work with during those initial six months of his transition from Yale to Harvard. Sometimes, though not often, he would get caught up in a work obsession to “get things done” and forget the small courtesies of gratitude that make a huge difference in the lives of administrative assistants and office workers. However, to his credit, when I reminded him of his lack of courteous gratitude, he was equally attentive to a need for repentance. It was a source of humor for both of us.

I left his tower office for the last time in the autumn of 1984. I was moving with others to start a new rural Catholic Worker community called Noonday Farm. Henri walked me down the stairs with an affectionate arm on my shoulder and said, “Michael, I have discovered with some chagrin that sometimes I am exactly like my own father. I brag to everyone else how grateful I am for the great work you have done for me over the last six months. But I must confess that sometimes I neglected to express that deep gratitude to the person who needed to hear it the most. So thank you.” At the bottom of the long wooden staircase that smelled of lemon and linseed oil, he reached out with those unmistakably expressive arms and hands to give me a bear hug of gratitude.

In the spring of 1985, Henri made the difficult decision to leave Harvard Divinity School and accept an offer to be a pastor for L’Arche/Daybreak in Toronto, a community of able and disabled people sharing life together. He had consulted me during his discernment process. I asked him, “Henri, do you want to heal your soul? Go to L’Arche, because there you will learn a new language for love and community from mentally and physically disabled people who cannot read your numerous books and some that cannot even speak. They will be your true and practical teachers of what it means to be a wounded healer in a broken world.” He had after all, lived and worked all his life in privileged academic settings, which I dare say aren’t the best places to learn about one’s brokenness, woundedness, or internal disabilities.

On his way to Toronto, Henri stopped with a caravan of friends and trucks at the Catholic Worker Noonday Farm community in Winchendon Springs, Massachusetts, where I was living and going to nursing school. He thanked me for our friendship and support for his new spiritual adventure and headed off to become the invited pastor of the L’Arche Toronto community.

I moved to California in 1988 to be closer to my soul-friend and mentor, the monk Father Aelred Squire, and to continue my work with poor and homeless people with HIV/AIDS as a registered nurse in Oakland, California, under the auspices of the Minority AIDS Initiative. I had spent the previous year as a newly minted RN working on a dedicated AIDS unit at the Shattuck Public Hospital in Boston. There, in the pale green painted rooms that always smelled of antiseptic, I saw and felt and touched the unspeakable and emaciated suffering of young gay and addicted men (and a few women of color) dying in their beds: some rejected by families, others stigmatized by friends, and all ignored and persecuted by government policies and laws. I was face to face with a modern incarnation of the crucifixion that lasted days and months—not three hours.

Henri and I continued our evolving friendship through correspondence, phone calls, and occasional visits. He was keenly interested in hearing about my AIDS work at the hospital in Boston and in the black community of Oakland. He wrote in a letter to me, “You have more to say about AIDS than anyone I know or have read. There is such a need for a truly faith-filled response to the AIDS crisis.”

After a year as pastor serving the Daybeak community, Henri experienced the darkest hour in his life, his “dark night of the soul,” precipitated by a break in a friendship at Daybreak. He plunged into a profound and paralyzing depression that required him to leave the Daybreak community for months of intensive residential daily therapy. Throughout this he never lost his ability to write, and in time he slowly recovered.

While serving in the black community as a nurse case manager, visiting dying people in their homes and on the streets, I realized that there was no residential hospice for homeless people with AIDS in the East Bay (there were, however, four in San Francisco where the pandemic was most pronounced). I prayed that God would open up a path to the possibility of opening a Catholic Worker house of hospitality. Henri shared that prayer with me, and cautioned to be careful what we pray for lest we receive it!

In 1990, thanks to the generosity of the Redemptorist community at Holy Redeemer Center in Oakland, that prayer was answered. Bethany House of Hospitality, a Catholic Worker residence for homeless people living with HIV/AIDS, opened its doors to welcome the homeless and weary sick and dying. It was a three-bedroom home, recently remodeled, with a little creek running through the backyard. Henri was ecstatic at the news and wrote, “I am excited you are doing this and I really hope you will find the moral and financial support you need. . . . I do want to help you in some way . . . so if you think a fundraising lecture by me in the future might be of help, let me know.”

Henri was true to his word. Every year until his death in 1996, he came to Bethany House to do a fundraising lecture at a local church and once at St. Mary’s Cathedral in San Francisco, a city where AIDS was ravaging the gay community with hundreds dying of the disease. There was no charge at the door for the lecture as we did not want to exclude anyone from attendance. We simply passed the collection basket. The loaves and fishes multiplied every year he came. He never took a fee for the public lecture.

He visited the guests at Bethany House, spoke to each of them with compassionate attention, and blessed them at their invitation. He also listened attentively and even wrote them letters. To our longest guest, Henry Bender, who was abandoned by his family and wounded in the Vietnam War, he wrote: “It has been such a great joy for me to come to know you, and to be aware of your peace filled presence in Bethany House. I will always remember how you worked in the garden, and made it such a beautiful place. I also remember your gentle face, and the way you smiled at me. As you live these last days of your life and are making yourself ready to make the great passage into the embrace of God, I just want you to realise how close I feel to you, and how much I want to assure you that the love you have experienced at Bethany House, from Mìchael and others, is only a small fraction of God’s love who will welcome you home. Thanks so much for your life, and for being a small, but very important part of my life.” Henry died peacefully in his bed after being a resident for more than three years. The sacred chant Kyrie Eleison resounded through his room as he took his last earthly breath.

In Henri’s final year that he spent as a sabbatical, he visited Bethany House and stayed several days at the Holy Redeemer Retreat Center with friends and guests. Though located in East Oakland, one could hear frequent gunshots in the night air. Holy Redeemer was a large compound, a former seminary with lots of open spaces and refreshing greenery. Henri treasured his visits there. He said he felt an inner freedom to be himself, his whole self, especially with his gay friends.

Henri was truly a seasoned teacher, a popular author, and a faithful friend who attracted large crowds at his lectures and homilies. When he spoke publically, every fiber of his being conveyed the passion of his faith and the gospel message for the modern world of God’s unconditional, compassionate, inclusive love and thirst for justice, the public face of love. He was a restless student of the painful yet grace-filled process of moving from resentment to gratitude, hostility to hospitality, and oppressive fears to all-inclusive loves: themes he spilled much ink writing about with experiential insight and messy humility. Hence his last words to a friend in the Dutch hospital where he died of a second heart attack: “I don’t think I will die, but if I do, please tell everyone I am grateful.”

The last time we spoke on the phone was a few weeks before he left for Europe to make a film for Dutch television on the theme of his book The Return of the Prodigal Son and on Rembrandt’s famous painting of the parable in the collection of the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. We planned to spend a week together at Daybreak in October. That meeting never happened due to his death on September 21 in the middle of the night. In the darkness, the prodigal son Henri Nouwen returned to his merciful, loving Father. He was finally welcomed home after a restless, anxious, fearful yet fruitful pilgrimage with a warm, gentle, forgiving embrace of unspeakable joy and tears of gratitude that glistened with the fullness of divine, luminous light.

My last gesture of friendship to Henri was to place my necklace of wooden rainbow beads anchored by a small Salvadorean cross in his hands as he lay in his open coffin at L’Arche. He already had a rosary wrapped around his hands, so I wanted those who came to pray at this coffin to see that this rainbow was not only a sign of resurrection hope given by God to Noah, but also a symbol of Henri’s identity. Though Henri never came out as a gay man publicly for various reasons, his death now liberated that intrinsic aspect of his being. Henri was buried with those rainbow beads and cross.

Michael Harank is currently a registered nurse working with poor and marginalized patients at a public health clinic in Berkeley, California. He was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War and began his pilgrimage as a Catholic Worker in New York in 1978, a journey that is ongoing to the present day.

This is really a great piece for so many reasons. A helpful way of getting to know both Henri, Michael and the people they have both supported. Stories like this are critical to our learning about each other, learning about faith and hope. It’s also amazing how connected we all become through values of hospitality, community and struggles for peace. Anyway a great article/reflection. Thank you Michael for sharing but more importantly for doing all of the things that you have done and continue to do.

Thanks Jim … writing it was a work honoring our friendship and love.

Michael, Thanks for this work of Love to craft a life time of memories of Henry as he traveled along all the paths in this life we share.

Bill

Hola Michael gracias por ayudar a todos los que te necesitan y por ser un activista un abrazo