Corruptions of the Heart by Nancy Enright

At Seton Hall University, where I teach, we have a course called Engaging the World, which is part of our university core curriculum and which links the Catholic intellectual tradition to various disciplines. This past fall I taught our upper British literature version of this course, entitled “Engaging the World: Fantasy and Faith—Tolkien, Lewis, and their Precursors.” The course is enjoyable to teach, and it attracts interesting and engaged students, many of whom are not English majors but trying their hand at upper-level literature through fantasy writers whom they love.

One of the most important aspects of the course is linking it to issues in the world today, in light of the theological insights of the writers we study. The recent and horrific spate of gun violence, particularly the mass shootings in Uvalde and Buffalo, caused me to think about the course again and, in this case, what J. R. R. Tolkien’s writings specifically have to say about this topic of gun violence.

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is a novel about power, used and abused. In a sense, all weapons offer a kind of power, and the choice to use them or not is a moral one. The many arguments against the limitation of access to guns turns on the right of “law-abiding citizens” to own them, with an idea of self-defense or perhaps pleasure from such things as hunting or marksmanship. Some particularly ridiculous responses to the tragedy of school shootings include suggestions to arm teachers or have armed guards outside of schools—anything to avoid limiting the excessive purchase of guns, which has led to such an enormous proliferation of them in our country that they outnumber people by a million.

Tolkien offers a few insights into this controversial topic, and they are well worth considering. In The Hobbit, he discusses the possible origin of such things as weapons:

Now goblins are cruel, wicked, and bad-hearted. They make no beautiful things, but they make many clever ones. They can tunnel and mine as well as any but the most skilled dwarves, when they take the trouble, though they are usually untidy and dirty. Hammers, axes, swords, daggers, pickaxes, tongs, and also instruments of torture, they make very well, or get other people to make to their design, prisoners and slaves that have to work till they die for want of air and light. It is not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them . . .

The idea that weapons were invented by evil creatures is not new to Tolkien. Milton also conveys a similar idea in Paradise Lost, where he gives devils the credit for the creation of guns:

They found, they mingl’d, and with subtle Art,

Concocted and adjusted they reduc’d

To blackest grain, and into store convey’d: [ 515 ]

Part hidd’n veins digged up (nor hath this Earth

Entrails unlike) of Mineral and Stone,

Whereof to found their Engines and their Balls

Of missive ruin; part incentive reed

Provide, pernicious with one touch to fire. [Book VI, 520]

Though both Milton and Tolkien would likely agree with the concept of a “just war,” and Tolkien himself fought in World War I, the attribution of the creation of firearms to evil beings suggests there is something intrinsically wicked about them, even when used as a necessary evil. Certainly, guns created for war, used to kill large numbers of people at once (such as the AR-15 used in the shootings at Uvalde), have no place outside of war and should not be available to civilians. Even in war, it could be argued that weapons that kill large numbers of people at once, with no ability to distinguish civilians from combatants, make modern warfare arguably never truly just. But that is another question . . .

Tolkien takes the idea of the use of weapons created for evil purposes a step further with his discussion of the Ring itself. Much debate goes on at the Council of Elrond in The Fellowship of the Ring about whether or not the Ring can and should be used against Sauron, i.e., for good. Though Boromir, sounding a bit like those who argue that guns in the hands of the good will be protective, makes the point that the Ring has come to the free peoples of the West (Elves, Dwarves, and Men) providentially, to help them to fight Sauron by using his weapon against him. He asks, “Why should we not think that the Great Ring has come into our hands to serve us in the very hour of need? Wielding it the Free Lords of the Free may surely defeat the Enemy. . . . Valour needs first strength, and then a weapon. Let the Ring be your weapon, if it has such power as you say. Take it and go forth to victory.”

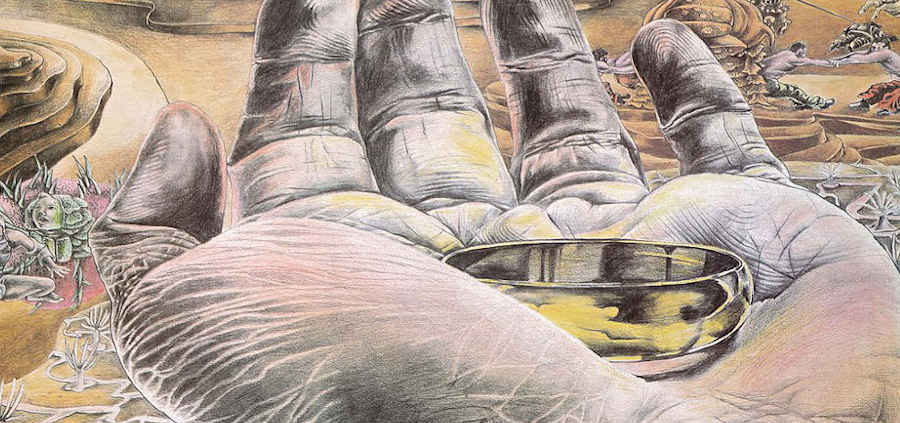

The problem is that evil is bound up in the very nature of the Ring. As Elrond says, “it is altogether evil . . . The very desire of it corrupts the heart.” Tolkien is not talking about an ordinary weapon here, and the good characters, like Aragorn and Faramir and even the Hobbits, use the ordinary weapons of their day, swords. However, there is something evocative about the evil inherent in this more powerful and seductive weapon being corruptive even to the good. Even Gandalf and Galadriel, among the wisest in Middle Earth, find the Ring tempting.

Whether this quality of corrupting influence and seduction might be argued about all guns (and I think perhaps it could), it could certainly be said regarding guns intended to kill multitudes of people at once. That potentiality amounts to scary and unnecessary power, way beyond what might be argued, somewhat implausibly, as the necessary evil of self-defense (as guns are often turned against their owners or used mistakenly by children or in the passion of a domestic argument). But large and powerful weapons are akin to the evil Ring that even the wisest and the best fear to handle or to use.

The final book of The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, reaches a climax when the two hobbits, Frodo and Sam, reach Mount Doom, where the Ring was created. There, Frodo finally succumbs to the temptation of the Ring and, instead of throwing it into the fire as he had intended, claims it as his own. Gollum, who had been spared by Frodo out of pity, returns and fights Frodo for his “precious” Ring, biting it with Frodo’s finger and claiming it for his own; gloating over his treasure, Gollum falls into the fires of Mount Doom, taking the Ring with him. The quest is fulfilled and the evil and temptation of the Ring destroyed, along with Sauron, its maker.

There are some things that are so entwined with potential evil that they must be kept away from those who might use them wrongfully. Ideally, they should be destroyed. Guns do not do evil by themselves, that is true, but, like the Ring, they can inspire evil in a heart already leaning toward violence, bringing the corruption that comes with the power to kill all too easily and swiftly. It is time to throw the Ring into the fire by stringently enforcing how and which guns can be purchased and by whom. Countries such as New Zealand have successfully followed this approach after a mass shooting. Perhaps after over 250 mass shootings in 2022 alone, we could learn from their wisdom and that of J. R. R. Tolkien, whose ideas regarding power used wrongly, evil, and the strength to reject both can speak to our society so badly in need of healing and peace. ♦

Nancy Enright holds a Ph.D. from Drew University. She is a full professor of English at Seton Hall University and the Director of the University Core. She is the author of two books: an anthology, Community: A Reader for Writers (Oxford University Press, 2015), and Catholic Literature and Film (Lexington Press, 2016) and articles on a variety of subjects, including the works of Dante, Augustine, J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis. Her articles have appeared in Logos, Commonweal, National Catholic Reporter, Christianity Today, and other venues.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!