Race and the Fall by Pieter Dykhorst

This essay originally appeared in In Communion, the official journal of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship (OPF). According to its mission statement, the OPF is “an association of Orthodox Christian believers seeking to bear witness to the peace of Christ by applying the principles of the Gospel to situations of division and conflict.” Readers of Today’s American Catholic are encouraged to seek out the work of the OPF, whose commitment to peacemaking, ecumenical dialogue, and other initiatives closely aligns with our editorial focus—Ed.

Racism cannot be addressed in isolation. Racism at its root springs from human divisiveness and our fallen propensity for conflict across difference, any difference. Racism, like each and every -ism ever created, is a manufactured, codified system of exclusion across some broken human boundary.

We often give lip service to fighting racism while we hide our bigotry in other places. It is common in the Orthodox Churches, for example, to utter condemnations of racism and ethnopyletic nationalism and then defend and deploy our religious, cultural, and civic nationalisms against all those we wish to exclude while pretending we are defending. This is apparent in places like the Balkans, Syria, and Russia and Ukraine, but American Orthodox are just as exclusive in this regard. It’s fine to speak against border walls running past somebody else’s property in another state, or for Antiochian churches to sponsor Syrian immigrants, but you aren’t a Christian in America until Latino migrants are sitting in your pews and serving at your altar.

We must unravel the “otherism” at the core of human nature that infects all relations and from which racism springs. If we cut off the head of racism, the beast will grow a head of tribalism, culturalism, classism, civilizationalism, regionalism, fundamentalism, globalism, or some other damned thing to either keep out, kill, marginalize, neutralize, or convert everyone else to its own cause and make them in its own likeness. The inclusive circle we draw will always have someone standing outside of it. There is a hidden something that has poisoned our souls and from which all our relational divisions arise. It caused Adam and Eve to fear, deflect blame, and hide. It first appeared in the human heart the instant of the fall and has been there ever since. To quote Metropolitan John Zizioulas,

There is a pathology built into the very roots of our existence, inherited through our birth, and that is the fear of the other. This is a result of the rejection of the Other par excellence, our Creator, by the first man, Adam. The essence of sin is the fear of the Other, which is part of the rejection of God. This results in of all otherness. We are not afraid simply of certain others, but even if we accept them, it is on condition that they are somehow like ourselves.

A second Fall narrative is recorded in Genesis 11. God observes that all people spoke “one language and had the same words.” The word “language” and the phrase “the same words” is not a literary redundancy in the Hebrew text; rather “words” is a word with over a hundred renderings in English, including “acts, affairs, answer, business, commandments, conclusion, conditions, conduct, conversations, matters, obligations, order, custom, thoughts.” Essentially, the text says “they spoke one language and had one uniform culture and acted in complete harmony and conformity.”

Yet God also observed, with apparent alarm, that the oneness for which we were created had somehow become perverted, and so God mixed up our languages. The effect was the fracturing and scattering of humanity “across the face of the Earth” and the eventual creation of disparate histories and culture with seemingly little in common. Why would God do this? Was this a false unity, built something superficial like culture, language, or race? As Metropolitan John argues, unity that rejects difference is no unity:

When we fear otherness, we identify difference with division. We divide our lives and human beings according to difference. We organize states, clubs, fraternities and even Churches on the basis of difference. When difference becomes division, communion is nothing but an arrangement for peaceful co-existence. It last as long as mutual interests last and may easily be turned into confrontation and conflict as soon as these interests cease to coincide.

The effort to force unity across difference with the singular purpose of returning the world to one uniform rule and way of life has occupied us ever since the fall. Yet, in Christianity we are called to a deeper communion. St. Paul implores:

Now I plead with you, brethren, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you all speak the same thing, and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be perfectly joined together in the same mind and in the same judgment (1 Corinthians 1:10).

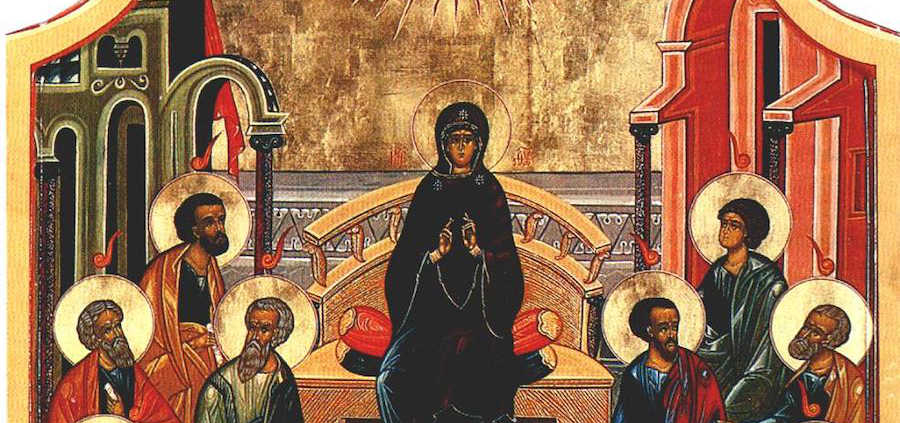

There is hope for a true unity, just as we sing at Pentecost:

When the most High came down and confused the tongues,

He divided the nations; But when he distributed the tongues of fire

He called all to unity. Therefore, with one voice, we glorify the All-holy Spirit!

Since the reversal of the curse of division at Pentecost, Christians have understood that the only thing capable of undoing the evil that embedded itself in Adam and Eve’s hearts is a new kind of kingdom apart from the kind of unity humankind experiences in the world. Nothing human beings do outside God’s Kingdom to solve what is wrong in us will ever reverse the curse of division. No political agenda or social program will save us.

To overcome our fundamental divisiveness, we must ground ourselves again in the New Testament. St. Paul’s letters are a manifesto of unity. And when Jesus sent out his disciples, it was to the whole world and to every nation scattered therein that he sent them. At Pentecost, the meaning of the “salvation of the whole world” was made clear. “The healing of the nations” had come and would eventually include persons ransomed “from every tribe and language and people and nation,” which was the reversal of the curse of the fall and the fracturing of humanity at Babel. Or as St. Paul wrote:

There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all, who is above all and through all and in all (Ephesians 4:4-6). ♦

Pieter Dykhorst is an editor at In Communion and member of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!