Beyond Reform by Eileen McCafferty DiFranco

Emily Dickinson called hope a feathered thing perching in the soul that sings its little heart out through storm and chill.

Hope and I have long had a good relationship. It is this cardinal virtue that usually encourages me to sing one more song even though the chilly storms of life too often deplete my repertoire. I am simply loath to call defeat. My personal sense of hope makes me an eternal optimist. I always think that things can be or get better. This ever present sense of great expectations prevents me from becoming bitter. It keeps my feet marching and my soul singing.

Like all virtues hope has a very distinct downside. Gamblers always hope their next bet will hit the jackpot. Addicts keep hoping for a perfect high; romantics, for a perfect lover. The naive expectation of success without plan, practice, or study often gets renamed as hope. In my case, my optimistic side has a twin named cynicism that presents its face when the landscape becomes too familiar.

Unfortunately, my cynical side slides right into place when I think about the upcoming synod. As much as I would hope that the Catholic Church would or could change, I am not the least bit hopeful that the synod will do anything to change the trajectory of an ecclesiology that arcs towards the preservation of power rather than justice. In fact, I fully expect that the church will turn its back on many if not all of the heartfelt suggestions made by hopeful, faithful Catholics who only want the best for their church. How do I know this? History and experience.

While history is certainly not destiny, it often fills in the upcoming blanks. Faithful people have been trying to reform the church for the last thousand years. Their efforts have never been rewarded. Instead, the names of the reformers fill the ranks of heretics while those who defended the church against reform and persecuted the reformers have received the esteemed title of saint. The faithful actually pray to men who have preached bloody crusades against their fellow Christians.

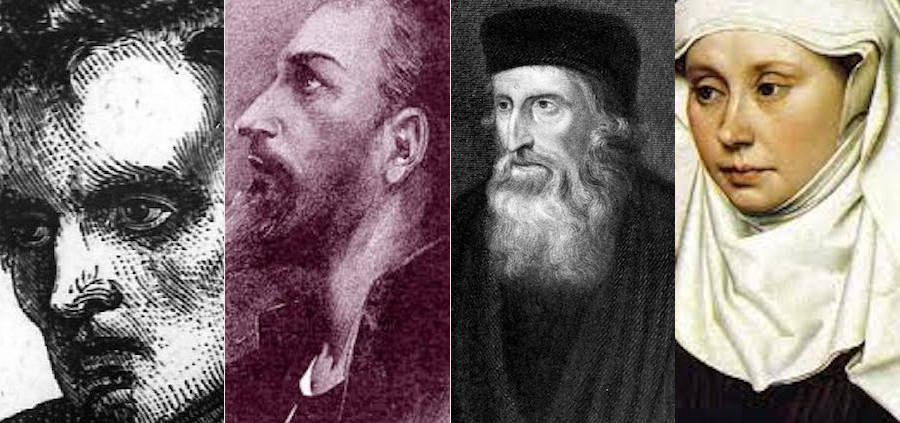

Arnold of Brescia (1090–1155), John Wycliff (1331–1384), John (Jan) Hus (1369–1415), and Marguerite Porete (1250–1310) tried to recall the church to the kingdom values of Jesus, to make the word of God accessible to the people of God, and to be advocates of the Prince of Peace. All except Wycliff met with a disastrous end via execution. Wycliff’s remains were disinterred and thrown into the Thames some 30 years after his death via an edict issued by the Council of Constance (1414–1418). The bishops in attendance at the council had Czech reformer Jan Hus executed after promising him safe conduct. In an egregious sin against hope called presumption, the mitered attendees declared there was nothing more to do with a man whose only request was to be proven wrong. Before his execution, Hus knelt down and prayed for the men who ordered his execution.

While reformers in the 21st century don’t lose their lives, they often lose their livelihoods. Theology professors like Charles Curran lost his position at Catholic University for supporting birth control. The very few priests like Roy Bourgeoise and Tony Flannery who dared to speak up for women were defrocked even as their confreres who engaged in the sexual abuse of minors were protected. Orders of nuns were visited by modern agents of the inquisition. Men and women in religious orders were silenced; their books, condemned. Members of the laity who support the ordination of women allegedly excommunicate themselves as do women who are ordained.

While Francis appears to be a kinder, gentler version of the far-too-numerous-to-count popes who rampaged through history calling for crusades and inquisitions and hurling anathemas at anyone who disagreed with them, he remains at the mercy of a thousand-year-plus, deeply entrenched bureaucracy which has rarely examined its conscience to determine its own role in causing the repeated call for reform. Why shouldn’t John Wycliff and Jan Hus have condemned crusades waged by Christians against fellow Christians? Why would Arnold of Brescia not denounce the princes of the church who lived in sartorial splendor in gleaming palaces? Why wouldn’t Marguerite Porete deplore ascetic practices like beating and starving oneself for Jesus? In a world filled with vast inequalities, the misapplication of natural resources, and climate degradation where women constitute 66 percent of the world’s poor, why wouldn’t theologians like Charles Curran support birth control?

All of the executed and punished reformers throughout the centuries have asked the church appropriate questions that deserved well-reasoned responses. Instead, the church’s response has always been an act of physical, spiritual, or mental violence. Their rationale? Only they, the men with clay feet peeping out from under their watered-silk cassocks know the mind and intention of God who specifically chose to reveal “himself” to violence-prone, power-obsessed ecclesiasts. Reforms from outside of this carefully constructed framework of inward-looking privilege are not only unwelcome, they are heretical.

Even the cataclysm of the Reformation did not change the mindset of the hierarchy. Instead of trying to understand the underpinnings of the greatest threat to their sovereignty, they shored up their power with the Council of Trent, spottily attended by mostly Italian cardinals who often jockeyed for the title of pope which came with immense wealth for them and their families. Trent “discovered” 1,600 years after the founding of Christianity that ordination came with an indelible mark on the soul and an accompanying magical connection with the divine that endowed the clergy with a power that brooks no challenge. This self-conscious understanding and adoption of ordained power is also a sin of presumption. The sin is visible to even the most casual observer. The all important, indelible mark of ordination quite obviously has not made the ordained kinder, wiser, better, or holier men.

It was the good feelings inspired by from Vatican II that obscured the ongoing egregious omissions and commissions of the church. The council also gifted believers with an unwavering source of encouragement and nurtured the hopes of subsequent generations of Catholics. Entrenched practices like the Latin language and the priest facing away from the people disappeared, seemingly overnight. These changes put a human face on a faith largely focused on life in the next world rather than life on a problematic earth. All things seemed possible in the reconstruction of the church as the People of God, an entity seemingly endowed with agency.

This hope for ongoing change was but a gossamer thing whose perch was roughly dismantled and ground into the dust by John Paul II. He and his cadre of obedient bishops and priests nailed shut the windows so joyfully opened by John XXIII, ushering in a new chill that froze the hope blooming all over the world.

The spirit of Vatican II was and remains an anomaly, a fleeting feathered hopeful blip upon the church horizon. What appeared to be seismic changes were mere window dressings. Even the much-vaunted Catholic social teaching, largely a development of Vatican II, got quickly buried by the church’s power paradigm. The sainted, heresy-hunting John Paul II refused to understand the base communities in Central and South America as a reform of unjust ecclesiastical and secular power structures. Instead, he chose to view reform as communism. He left the archbishop of El Salvador, Oscar Romero, out to dry. Romero, six churchwomen, the Jesuits and their housekeepers at the Central American University, and countless numbers of innocent people were assassinated by loyal, obedient, church-going death squads who feared sharing their privileged place in the world with those beloved by Jesus.

Institutions based upon power and privilege usually talk a good game, promising rewards in this world and, more importantly, in the next. The voices offer comfort on a stick as they cajole and finally threaten. We should always examine what they do instead of what they say. The upcoming synod is a prime example.

Many bishops are not leading their flocks in any sort of forum to discuss reform. A friend was dismayed by the listening session she attended in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. In her words, “The archdiocese did a process to say they did but did not do so with a lot of energy, passion, or creativity.” The very same thing happened at a synod held in Philadelphia in 2002. I attended one of those sessions. That synod was a rubber stamp wielded by an iron fist. We were directed that any topic that did not reflect church dogma and doctrine was verboten.

The bishops’ lack of engagement in the synodal process should not be surprising. They already know without a shadow of a doubt what the hopeful are hoping against hope for won’t come true. My cynical self knows the answer. Nothing will change, so why bother?

As many faithful Catholics like to say, the church is not the hierarchy. It is, however, the hierarchy who sets the policies, the procedures, the rules and regulations that all are obliged to follow. It is the hierarchy who foisted the new order of the Mass with its clunky translations and its constant, annoying reference to the Almighty as “He.” It is the church that continues to pursue gay people and fire them from their jobs. It is the church that bans women from ordination. And it will be this same church that will control the outcome of the synod. The obedient clergy will follow in lock step. Their very livelihood depends upon their unwavering obedience, even in the face of great sin. It is for this reason that the church cannot and will not be reformed.

It is that mode of church that has hurt and continues to hurt people across the centuries. It is that model that must be discarded and replaced, not at the Vatican’s glacial pace, but now with the voices of the synod as a corrective. My cynical side assures me that this will not happen. However, other things will.

As the poet Langston Hughes so plaintively asked, “What happens to a dream deferred?” Does it fester, stink, and sag? Does it explode?

I would say that the institutional church will gradually fizzle out like a deflated balloon. Declawed and defanged by its own excesses, most people are simply walking away from the Catholic Church to different sects or engaging in what are for them more life-giving rituals and practices.

And that is not bad news. Resurrection is the core belief of Christianity. A resurrected body might look different and feel different from the one we are used to seeing. It may even be unrecognizable at first as the resurrected Jesus was to his friends. That doesn’t mean a new, different-looking church without ecclesiastical accoutrements is not real or true or worthy to be called the church of Jesus.

The good news in leaving the institution is that we can always find God in the breaking and the sharing of the bread, however, whenever, and wherever that occurs. For it is in the sharing of bread for the life of the world that hope in our souls springs eternal and the world is made new. ♦

Eileen McCafferty DiFranco is an ordained Roman Catholic Womanpriest and the co-pastor of Saint Mary Magdalene Community in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. TAC’s 2021 profile of her life and work, including an excerpt from her book How to Keep Your Parish Alive (Emergence Education Press, 2017), is available here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!