Summer Reading Series: Julie A. Ferraro on Michael Patrick O’Brien

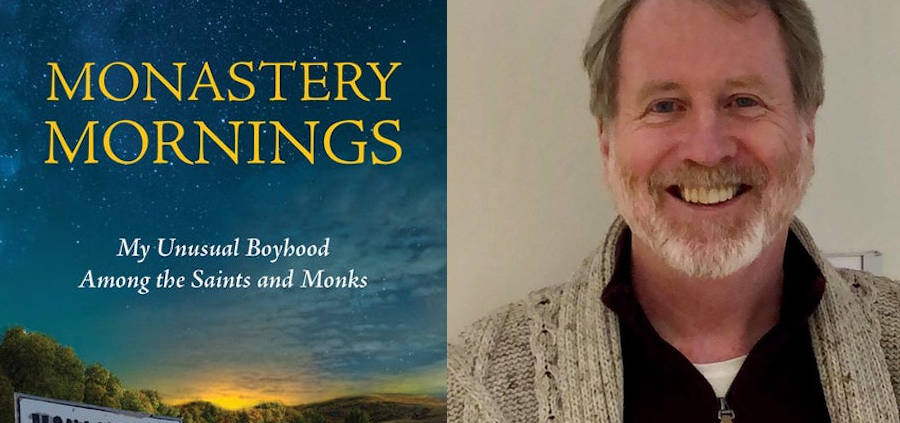

Monastery Mornings:

My Unusual Boyhood Among the Saints and Monks

By Michael Patrick O’Brien

Paraclete Press, 2021

$18.00 192 pp.

Trappist monasteries, as a rule, are located in remote areas on vast acreage. The focus of Michael Patrick O’Brien’s recent book, Monastery Mornings, is the Abbey of Our Lady of the Holy Trinity near Huntsville, Utah. Thus the book’s subtitle—Among the Saints and Monks—with the “Saints” being members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, formerly called Mormons.

O’Brien recounts how he became familiar with the abbey by attending early morning Mass with his mother, soon after his parents’ divorce when he was nine years old. That was, however, after his family had moved from Vermont to Bermuda, then Louisiana and France, as the Air Force transferred his father.

Crediting “Irish DNA” for his conversational storytelling prowess, O’Brien writes in an easy and compelling style. His descriptions of people and places are reminiscent of classic authors, making it possible to “see” through his eyes, evidence that his voracious reading as a youngster added to his natural flourish with words.

The author’s mother had initially driven her children to Holy Trinity Abbey on an outing, 45 minutes from their home, and young Michael found himself in what he terms a “strange world” where the first monk he saw appeared solemn, yet not frightening. While browsing in the monastery’s book store and overhearing his mother being told that she, like so many others, were searching for peace, it touched the lad deeply.

O’Brien writes of his venture into the monastic cemetery, where the unusual names intrigued him. Asking some of the living monks about the deceased, he eventually embarked on a journey of research to get to know them better.

He summarizes the monastery’s history in one chapter, beginning with the July 1947 departure of three dozen monks from the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky. His own family’s Irish Catholic roots and meanderings through the 1960s and 1970s aptly convey the innocence and wonder of a youngster trying to figure out the deaths of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., while also puzzling over his mother’s fascination with the TV miniseries The Thorn Birds.

As he becomes more familiar with the monks, humor accompanies O’Brien and his siblings as they discern the true meaning of “None” on the daily horarium: “Maybe there used to be a service at that time that had been discontinued, and so they put ‘None’ on the schedule so people would know there was not a service anymore,” his sister Karen proposes. (“None” is Latin for “nine,” and is used to designate the monastic prayer at the ninth hour of the day.) The term “snow Mass” is calculated by the children to be “something like a folk Mass, only said outdoors and in bad weather,” when it actually refers to the Trappist monastery in Snowmass, Colorado.

O’Brien includes the monks’ varying senses of humor and the jokes they shared, along with their respective backgrounds from across the country. He breaks open the stereotypes of monastic life, from the folk Masses held at Holy Trinity Abbey in the 1970s to the very grounded and human personalities of the monks he became friends with over the years—even some who left the monastery to continue their lives elsewhere.

“We tend to think of monks as settled and secure in their spiritual life,” O’Brien states. He points to ways some of the monks expressed their doubts and admitted their struggles within the monastery, while continuing to be a prayerful presence not only for the local community, but through charitable efforts around the world.

In his youth, the author was granted access by the monks to areas usually closed to the laity, from the infirmary to the kitchens and elsewhere. He writes of the cattle herd tended on the grounds, and monks caring for the chickens and processing the eggs for sale.

O’Brien includes his own faith journey, developed through his interactions with the monks, his family, and the world. He describes in refreshingly understandable style the five vows professed by the Trappists: obedience, stability, poverty, celibacy, and conversion of manners.

The tale continues through O’Brien’s college years, becoming a lawyer, marrying, and raising his own family. He laments the child sex abuse crisis, facing his own quandary as to whether to leave the church, and the closing of Holy Trinity Abbey in 2017, with the remaining few monks transferring to other monasteries or an assisted living facility.

I’d initially wondered if, as described on some websites, this “love letter to a community of Trappist monks” would be a sappy and saccharine look at monastic life. But I was pleasantly surprised with this book. It provides valuable insights, the kind readers will find inspirational and thought provoking. O’Brien’s research is thorough (as seen when browsing the end notes), but he eschews scholarly terms. The chapters vary in length from two pages to 20, but the story is compelling and well worth the time. And for those who may be interested, O’Brien continues to write at his blog, A Boy Monk, which he describes as “A friendly conversation about church, religion, spirituality, life, family, and travel in the twenty-first century.” ♦

Julie A. Ferraro has been a journalist for over 30 years, covering diverse beats for secular newspapers as well as writing for many Catholic publications. A mother and grandmother, she currently lives in Atchison, Kansas. Her column, “God ‘n Life,” appears regularly in Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!