Light of Tabor: A Transfiguration Meditation by Michael Centore

After six days Jesus took Peter, James, and John and led them up a high mountain apart by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them. Then Elijah appeared to them along with Moses, and they were conversing with Jesus. Then Peter said to Jesus in reply, “Rabbi, it is good that we are here! Let us make three tents: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He hardly knew what to say, they were so terrified. Then a cloud came, casting a shadow over them; then from the cloud came a voice, “This is my beloved Son. Listen to him.” Suddenly, looking around, they no longer saw anyone but Jesus alone with them.

—Mark 9:2–8

From where I live in Connecticut, I can see to the west a narrow ridge of igneous rock known as the Metacomet Range. The ridge runs the length of the state from south to north and into Massachusetts for a total of 100 miles; its highest point is a mere 1,269 feet, but it represents, for those of us in the low elevations of the Connecticut River Valley, one of the region’s most dramatic geological features.

Igneous rock is created when hot, molten magma erupts through the earth’s surface, cools, and solidifies; it is rock created by fire. I think of this when, at dusk, I face the ridge and pray the Phos Hilaron, an ancient Christian hymn translated as “O Gladsome Light”:

Now that we come to the setting of the sun

and behold the light of evening,

we praise the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit . . .

To sing words dating from the fourth century that have passed through so many hearts and minds and mouths hymning so many sunsets across so many continents deepens my sense of space and time. Added to this is the experience of watching the sun’s azimuth make its annual passage up and down the length of the ridge, from south in the winter to north in the summer, in a movement that recalls a great eye opening and closing and that lends a celestial rhythm to my prayer. An anonymous Carthusian writes:

It is hard to leave the fashioning to God in such a way that we renounce all self-determination, in any given moment, to remain simply before God for the unfolding of our life, for what has been and what remains to be. To persevere in a sort of open expectation, without anxiety, without forcing a conclusion. Nothing else.

The word fashioning here acquires new richness when contemplating the surface of the earth, continually shaped and reshaped by geological processes that affirm the psalmist’s vision of deep time: “To you, a thousand years are a single day, / a yesterday now over, an hour of the night” (Ps. 90:4, cf. 2 Pet. 3:8). The fire of the rock and the fire of the sun fuse into one image of creative conflagration: it is the fire of the burning bush that blazes but never destroys, the fire before which God made Moses remove his shoes because it was holy ground (Exod. 3:5).

If we look with the eyes of prayer, we begin to see this holy ground is everywhere. Just as God called out to Moses from the middle of the burning bush, so does he call out to us from the core of the earth. Just as that core is divided into an inner sphere of solid iron surrounded by a sea of molten metal, so is God’s unchanging nature clothed in the fluidity of fire.

In the second book of his treatise On the First Principles, Origen of Alexandria uses this image as a means of illustrating the conjunction of the divine and human natures of Christ: “In this way, then, that soul which, like an iron in the fire, has been perpetually placed in the Word, and perpetually in the Wisdom, and perpetually in God, is God in all that it does, feels, and understands.” The historian of Byzantine philosophy Dmitry Biriukov elaborates:

By the example of penetration of fire into iron, Origen here demonstrates, first, that the soul of Christ is entirely penetrated with divine properties and accepts them; second, that as the heated iron becomes a source of heat and light, the soul of Christ is a source of divine heat for people; and third, giving an example where the iron is always in fire, Origen postulates immutability of unity of Christ’s soul with God.

Biriukov also shows how the image of the penetration of fire into iron has been used in theological literature to describe theosis, the process by which a person is unified with God to become a “partaker of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4). He quotes from a homily of Pseudo-Macarius:

Like the body of Christ, being mingled with the deity, is God; like iron cast into fire is a fire, and nobody can touch or approach to it without fearing to be eliminated or extinguished . . . the same way any soul purified by the fire of the Spirit and having become itself fire and spirit, can be together with the pure body of Christ.

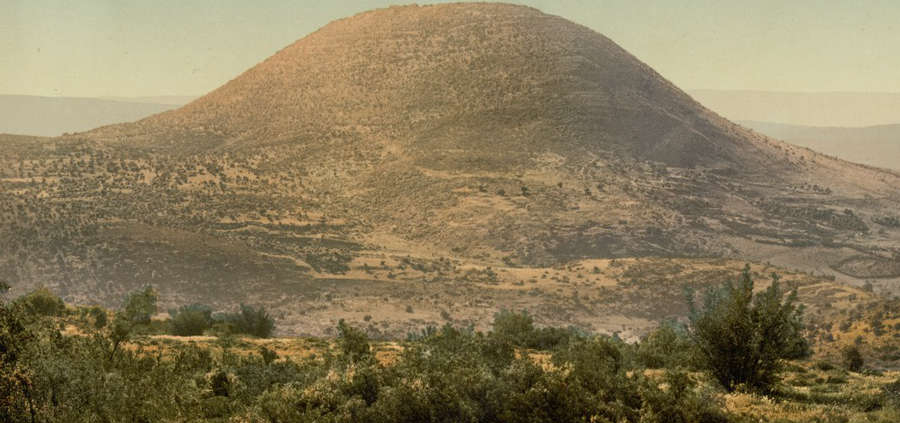

I think of this image especially during the Feast of the Transfiguration celebrated on August 6. The Transfiguration is a feast of fire, when the uncreated light shines through the contours of the face of the human, historical Jesus; here is the moment when “his clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them” (Mark 9:3) and his “pure body” stands revealed in its immutable unity with God the Father. The perichoretic dance of the Trinity projects itself in all its outward power as the Son is irradiated by his own divine light that cycles through the fire of the Spirit. Contemplating this, we are swept up, like the disciples, into the mystery of his glorification and drawn nearer to the inner heat of the Trinitarian movement within ourselves. Here, in the quiet stillness of God’s presence, the transfigured light of Tabor combines the heavenly and the terrestrial, the celestial and the telluric, to ultimately burn the boundaries between them in the fire of divine love. ♦

Michael Centore is the editor of Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!