Two Latino Leaders, One Message of Love and Hope by Maribel Landrau, M.A.T.

In 2013, the Holy Father Pope Francis imparted an Apostolic Blessing to the Catholic Studies Program at Seton Hall, where I serve as the Assistant Director of the University Core Curriculum. Seton Hall is proud that the university is the first and only American university to receive this honor. As stated in 2013 by Dr. Gabriel Esteban, president of the university at the time, the Apostolic Blessing to the Catholic Studies Program is a testament to the university’s continued dedication to fulfill the Catholic mission.

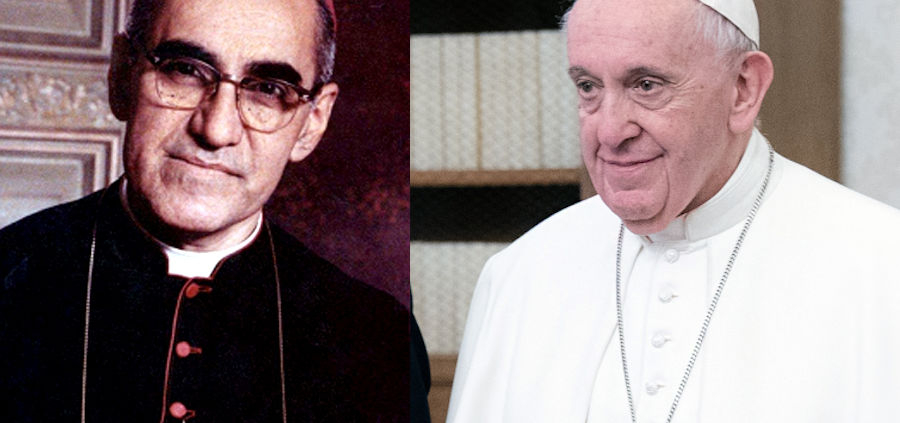

The University Core consists of three “signature” courses required of all students. The Core is rooted in the Catholic intellectual tradition and works closely with the Catholic Studies program in living up to the integration of mission and academic life that is essential to a Catholic university. Both Saint Oscar Romero and Pope Francis have made tremendous contributions to mission and scholarship; and both, being Latino in background and language, bring an important expression of diversity to our curriculum. In light of these attributes, and because of the values that they have expressed and embodied, they are central figures in our Core and Catholic Studies program.

The Core and Catholic Studies program offer signature courses that teach the message of these great men of strong faith. Some of the courses include Journey of Transformation, Christianity and Culture in Dialogue, and History of Catholicism in Latin America. These courses teach students the importance of Saint Oscar Romero, not only during the time he served El Salvador in the ’60s and ’70s but also today, and the importance of Pope Francis, whose message continues to resound in our troubled world.

It is important to note that Pope Francis canonized Saint Oscar Romero. Perhaps he identified himself with Romero and his message of love and hope, giving a voice to those who are voiceless. Both men taught and evangelized at many levels in what the mission and message of the Catholic Church is, based on Sacred Scripture and Christ’s example. A look at their backgrounds and ministries shows further links between them.

Saint Oscar Romero: The Voice of the Voiceless

Oscar Arnulfo Romero Galdamez—what a long name for a saint! Like all Latinos, Romero carried his mother’s last name along with his father’s name. Saint Oscar Romero was one of eight children born to Santos Romero and Guadalupe de Jesus Galdamez in Ciudad Barrios in El Salvador. The town of Ciudad Barrios was accessible only by horseback or by foot during Romero’s childhood. It was close to the Honduran border. While not a wealthy town, Ciudad Barrios was economically stable.

At an early age Romero showed passion for school and learning. He attended school for the first three grades and then was tutored by a teacher. However, his father wanted him to be a carpenter. In fact, when the boy was 12 years old, Santos pushed his son to learn the trade. Some say that his father had no interest in Oscar becoming a priest because of his own lack of faith. However, after some convincing, his father allowed young Romero to enter the San Miguel Minor Seminary at the age of 13. It is interesting that the people from Ciudad Barrios, including the mayor and the vicar general, had a premonition that Romero was meant for something other than carpentry. The San Miguel Minor Seminary was run by the Claretians, an order whose members are called to work with the poor and have a devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Saint Romero grew to love this devotion and kept it all throughout his life.

At the age of 20 Romero lost his father and his mother became ill. His faith helped him get through this difficult time. After his father’s death in 1937, the Bishop of El Salvador sent Romero to Rome to discern his future ministry, and, afterward, he was sent to live at the Colegio Pio Latino Americano in Rome. The Colegio specialized in preparing young Spanish-speaking men from Central and South America for the priesthood. While in Rome, Romero attended Gregorian University, which was founded in 1858 and staffed by Jesuits. In 1942, at the age of 25, he was ordained as a priest and headed back to his homeland of El Salvador, only to face multiple challenges. Father Romero celebrated his first Mass at his hometown Ciudad Barrios on January 11, 1944, and 26 years later he was consecrated the fourth Bishop of El Salvador.

Oscar Romero, Vatican City, 1942

During Romero’s time as the leader of the Catholic Church in El Salvador, the country was suffering from a corrupt military government and an impoverished society. He suffered poor treatment by other priests who, at first (before he began speaking out) accused him of taking sides with the rich and, conversely, once he did speak out, of being a communist and siding with the campesinos (peasants).

The living conditions in El Salvador for the poor campesinos were horrible, and the military government was committing atrocities against them. The church was persecuted, and priests were being killed for their message of solidarity with the poor and their commitment to social justice. One of these atrocities was the brutal assassination of one of Romero’s friends, Father Rutilio Grande, and two of the four companions who were traveling with him on March 12, 1977. Father Grande had dedicated most of his life to the campesinos, those who did not have a voice because of their social status.

The death of Grande was a turning point for Romero, who evolved from a quiet and shy individual to become the “voice of the voiceless,” as he has been called. Romero scholars have referred to the change of attitude as the “Rutilio Miracle,” though some correctly make the point that these ideas of identifying with the poor were already developing within him from his earlier ministries as a young priest.

During the celebration of Grande’s funeral Mass, Saint Romero assured the government that he was God’s servant, not theirs. His message of grief and anger was a direct one to the president of El Salvador, Carlos Humberto Romero (no relation). Grande’s death was the last signpost in Romero’s long journey to discern exactly where God was calling him to serve. From then on, he looked to the Holy See to help him deal with a corrupt military government and the atrocities they were committing towards those campesinos without a voice, and also to help him resolve issues with his brother bishops in El Salvador.

Romero finally had a private audience with Pope VI, which was successful. The Holy Father encouraged him to keep dealing with the issues facing El Salvador and difficulties with the bishops, and reminded him to have courage because he was in charge. However, there were three popes during Romero’s time as archbishop, and the situation in El Salvador did not change. More and more priests were getting killed because of their message. Romero himself joined their company when he was assassinated on the altar on March 24, 1980.

Pope Francis: A Commitment to the Poor

Pope Francis’s upbringing and time as a priest were, in some ways, quite different from those of Saint Romero, but their message and their journey were similar. Jorge Mario Bergolio was born December 17, 1936, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the son of Italian immigrants. His father Mario was employed by the railways as an accountant and his mother Regina Sivori was a stay-at-home mom. Young Jorge was one of five children. The future Holy Father went to school and became a chemical technician, then later discerned a calling to the priesthood. In 1958 he entered the Society of Jesus and embarked in a journey in higher education. He earned various degrees in the humanities, specifically philosophy and also in theology. He taught literature and psychology in different institutions in Argentina. Ten years later, in December 1969, he was ordained as a priest and continued his training in Spain, where he made his final profession with the Jesuits. He then returned to Argentina to continue his work in higher education. Throughout Francis’s trajectory he has always been committed to higher education, always sharing the message of the Gospels.

A difficult time for Bergoglio was the so-called “Dirty War” in Argentina, when the government, in many ways similar to that in El Salvador in the ’70s, was oppressing the people, and members of the clergy were speaking out and sometimes persecuted. Again, we see how the church was persecuted because the clergy were the “voice of the voiceless.” These courageous priests were using their pulpits to demand change.

From 1973 to 1979, Bergoglio was a young provincial general of the Jesuits. In his biography The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope, Austen Ivereigh gives many examples of Bergoglio working behind the scenes to help others escape from Argentina during these difficult times. One example is the case of Father Juan Carlos Scannone, who was being held in prison and tortured; it was obvious he would get killed because he saw the face of his torturer. With courage Bergoglio negotiated the release of this young priest by telling the officer: “If you believe in hell, you should know you’ll get sent to hell for a serious sin.” The young priest’s life was safe.

Bergoglio always had a strong commitment to the poor, but he himself talks of having been too “authoritarian,” and it seems he was not as outspoken as he became later. After his position as head of the Jesuits, he spent time in the city of Córdoba reflecting and repenting on what he now considers mistakes from that period of his life. Since that time, Francis’s humility and his outspokenness have increased. As Wim Wenders, director of the film Pope Francis: A Man of His Word, has said of him, he is a man of enormous courage, unafraid to say whatever he feels is right: “His many talks all over the world, to refugees, prisoners, politicians, scientists, children, rich or poor or regular people, made me realize how courageous he was, how fearless.”

Bergoglio received several important appointments, including titular Bishop of Auca and Auxiliary of Buenos Aires by Pope John Paul II in May 1992. In 1998 he became Archbishop of Argentina, and three years later John Paul II created him a cardinal. During his time as Archbishop of Buenos Aires he served a diocese of 3 million inhabitants. As we can see now during his pontificate, Pope Francis is dedicated to serving those who need the most, the poor and the sick, and to giving voice to the laity within the church.

A Shared Message of Love and Hope

Though Saint Oscar Romero and Pope Francis evangelized and preached in different times and different countries, both leaders shared the same message of love and hope. Saint Romero kept sharing in his homilies with his people of El Salvador and giving hope with his message: “We hear the word, fit it to our circumstances, celebrate, are nourished in the life of Christ, and are led to commitment to duty, to home, and service in the world for living a life that is truly according to God.” Similarly, Pope Francis has explained the importance of the church in his message of hope and love: “The Church evangelizes and is herself evangelized through the beauty of the liturgy, which is both a celebration of the task of evangelization and the source of her renewed self-giving.”

Saint Romero’s time serving the church was not an easy one. The church was under attack and priests were killed. Saint Romero was full of grief and wept when seeing his friend Father Octavio Ortiz’s body unrecognizable after being brutally assassinated. Father Ortiz was one of the priests he had mentored and ordained. But his voice and message did not stop. During one of his powerful homilies on March 14, 1977, Saint Romero reminded his people: “let us not forget: we are a pilgrim church, subject to misunderstanding, to persecution, but a church that walks serene because it bears the force of love.” What is “the force of love” for us Christians? It is Christ? Yes! His example, as he articulated it: “I have told you this so that my joy might be complete. This is my commandment: love one another as I love you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13).

Pope Francis officiates the ceremony of the canonization of Oscar Romero, October 14, 2018

This message of love continues with Pope Francis. He began his pontificate March 13, 2013. We saw the type of leader the new pontiff would be the first day he addressed his flock and in his first writing, The Joy of the Gospel. The Holy Father did not disappoint. When he appeared to his flock and the whole world in Saint Peter’s Square as the new leader of the Roman Catholic Church, his message stunned the world. He asked for prayers for his predecessor Pope Benedict XVI. But what showed the world who he was going to be as the new Bishop of Rome were his opening words:

Now, I would like to give you a blessing, but first I want to ask you for a favor. Before the bishop blesses the people, I ask that you pray to the Lord so that he blesses me. This is the prayer of the people who are asking for the blessing of their bishop. In silence, let us say this prayer of you for me.

In his first Apostolic Exhortation, The Joy of the Gospel, Pope Francis addressed the world with a message of love and hope but also a message of evangelization. How do Christians bring the message of the Gospel to others? How can this message be share with our students so they can go into the world as servant leaders and make a difference? The Holy Father invites us to be joyful evangelizers: “In virtue of their baptism, all the members of the People of God have become missionary disciples (cf. Mt 28:19). All the baptized, whatever their position in the Church or their level of instruction in the faith, are agents of evangelization, and it would be insufficient to envisage a plan of evangelization to be carried out by professionals while the rest of the faithful would simply be passive recipients.”

During his homily on November 20, 1977, Saint Romero conveyed the same message as Pope Francis 36 years later: “How beautiful will be the day when all the baptized understand that their work, their job, is a priestly work, that just as I celebrate Mass at this altar, so each carpenter celebrates Mass at his workbench, and each metalworker, each professional, each doctor with the scalpel, the market woman at her stand is performing a priestly office!” The messages from these holy men are the same: it is our responsibility to bring the message of Christ to others. In my case, as a faculty member at Seton Hall, I teach this message along with my colleagues to young people in the classroom. The Holy Father explained it in a beautiful way in his Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Christus vivit (Christ is Alive!):

Anyone called to be a parent, pastor or guide to young people must have the farsightedness to appreciate the little flame that continues to burn, the fragile reed that is shaken but not broken (cf. Is 42.3). The ability to discern pathways where others only see walls, to recognize potential where others see only peril. That is how God the Father sees things; he knows how to cherish and nurture the seeds of goodness sown in the hearts of the young. Each young person’s heart should thus be considered “holy ground,” a bearer of seeds of divine life, before which we must “take off our shoes” in order to draw near and enter more deeply in the Mystery.

Conclusion: Servants of the Gospel

These two modern Latino leaders lived in two different countries and different times. However, they serve and proclaim a message of love, hope, and nonviolence, not only to their own people but to the whole world. How did Saint Romero share his message with the campesinos who had lost all hope? He witnessed violence and poverty among his people, and he used his pulpit to demand change. Francis uses his position as a world leader to convey the same message as Romero’s in today’s society.

Both servants of the Lord lived different lives. While Romero faced a time of corruption and violence in a small third-world country, Francis’s society today is full of much of the same challenges: hate, racism, religious intolerance, and poverty. The Holy Father received his degrees, taught in higher education, and was elevated to different positions within the church. Romero faced a country in war, suffering, and poverty, and a military government who did not respect simple human rights.

Today, many issues threaten the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. We live in a society that needs to be more compassionate to those in need. The issues of racism, hate, religious intolerance, and social justice are on the front line for the Holy Father Francis. We can read or listen to Francis’s message that “my people are poor, and I am one of them.” Both Romero’s and Francis’s central message mirrors that found within the Gospels, Jesus’s message, a message of social justice, love, and hope. As simple, but as challenging, as that. ♦

Maribel Landrau, M.A.T., is the Assistant Director of the University Core at Seton Hall University, where she teaches courses in Christianity and Culture in Dialogue and Latin American Catholicism.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!