Energy, Joy, and Solidarity: Carolyn Whitney-Brown on Henri Nouwen’s Experience of the Trapeze

In the late 1980s, Canadian writer, speaker, illustrator, and university teacher Carolyn Whitney-Brown and her husband were finishing their doctorates at Brown University after doing research at Oxford and Cambridge. They soon became wary of the highly competitive nature of academia. “We were running with the brightest,” she recalls of the time, but “we didn’t like the kind of people we were becoming.”

At the end of a year spent living with intentional communities in England, they wrote to the Dutch Catholic priest, author, and theologian Henri Nouwen, who had made the transition from the academic world to L’Arche Daybreak in Richmond Hill, north of Toronto, Canada. L’Arche is an international federation of communities where people with and without intellectual disabilities share their lives together. Carolyn and her husband relocated to L’Arche Daybreak, where they lived with Henri from 1990 until his death in 1996.

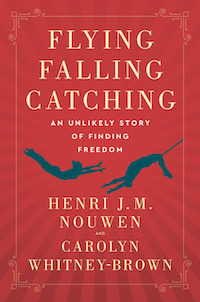

Carolyn’s latest book, Flying, Falling, Catching: An Unlikely Story of Finding Freedom, uses Henri’s journals, notes, reflections, and other materials as building blocks for a narrative about a particular and little-documented period of his life: the time he spent traveling with the Flying Rodleighs, a trapeze troupe who performed with the German Circus Barum, in preparation for a book about his experience.

Carolyn’s latest book, Flying, Falling, Catching: An Unlikely Story of Finding Freedom, uses Henri’s journals, notes, reflections, and other materials as building blocks for a narrative about a particular and little-documented period of his life: the time he spent traveling with the Flying Rodleighs, a trapeze troupe who performed with the German Circus Barum, in preparation for a book about his experience.

The Flying Rodleighs captivated Henri since he first saw their act in Freiburg, Germany, in 1991. The collaborative energy, gracefulness, and artistry of their routine struck a deep chord in him and opened up new zones of self-understanding in his roles as a writer and a priest. This was especially true of how his response to the Rodleighs helped him discover that “the body tells a spiritual story” separate from the heart and mind.

Henri’s work on the Flying Rodleighs never materialized before his untimely death at age 64, but the creative collaboration of Flying, Falling, Catching manages to both share the story he himself would have told while honoring his stated desire to produce a different kind of book than he had previously—something closer to a novel or a cycle of short stories that might even cross over to a secular audience. In this spirit, Carolyn set out to write “a book that would read as engagingly as fiction while using true events,” and the result is a seamless blend of memoir-like reflection and character-driven narrative. The hallmarks of Henri’s style—candor, vulnerability, rigorous attentiveness to his spiritual and emotional condition—are all present, but communicated through the movement of specific people, places, and events.

The book is framed by a strange but true event in Henri’s life. After checking into a hotel in Holland in 1996, he suddenly felt ill. The front desk called the paramedics, who found that he was having a heart attack; because the elevator and stairwells were too narrow, they had to take him out of his room through a window. In the excerpt that follows, Henri reflects on his life as the nurse overseeing the rescue prepares him for the lift. Texts in italics are Henri’s own words from his published or unpublished writings, talks, or interviews. Below the excerpt, we are pleased to share a video interview with Carolyn about the book along with some key quotes for those who prefer text. Special thanks to Carolyn Whitney-Brown for graciously answering our questions, and to Melinda Mullin at HarperOne for permission to use the excerpt—Ed.

♦ ♦ ♦

At the hotel in Hilversum, the ambulance driver shoves a large red emergency bag into Dennie’s hands. Dennie pulls out some extra medication.

“I will keep this with us in case we need it in the next few minutes,” he tells Henri. One of the firefighters is already waiting by the door with Henri’s carry-on bag. Dennie hands the emergency bag back to the driver, who runs out the door with the firefighter. “They are heading downstairs to meet us at the bottom,” Dennie adds.

He pauses, concerned by Henri’s lack of response. Is he distracted by pain, is he afraid, or is he losing consciousness? Dennie keeps talking to keep Henri alert and present: “Now we are ready to go down the hall to the window. The hotel has opened it for us, and we will load your stretcher onto the aerial lift. Don’t worry. I will be with you all the way.”

The blanket wrapped around Henri is warm. Henri opens his eyes and tries to smile at Dennie, but realizes Dennie cannot see his mouth twitch behind the oxygen mask. Dennie tucks the oxygen bottle securely between Henri’s legs. The heart monitor is held by one of the firefighters, who stays close so that the three leads remain firmly attached to Henri’s chest. Another is preparing to carry the IV bag. He is impressed by their care and coordination as they confidently reach for the equipment they need. Each seems to know immediately what is needed and take their role without confusion. They must practice this.

It’s another version of reaching out, Henri thinks. Reaching Out was the title of his second book, and Henri finds himself pondering how that book’s main points are like the trapeze. From the pedestal, the flyer has to reach out to the trapeze bar. The catcher reaches out for the flyer. Even the book’s subtitle emphasized motion and momentum: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life. When he wrote the book twenty-one years ago, he articulated an inward movement from loneliness to solitude, then an outward journey from hostility to hospitality, and finally an upward movement from illusion to prayer. Readers found it practical and helpful, a spiritual self-help book just as the genre was starting to take hold, and it became Henri’s first “best-seller.”

But now, blearily watching Dennie and the careful teamwork of his rescuers, Henri wonders if he was thinking too much of a spirituality for just the individual. How could anyone reach out in those ways alone? Without a sense of being part of a larger body, even a team or community? The question isn’t new. Already in 1983 while he was living in Latin America, Henri’s new friends revealed to him how individualistic and elitist my own spirituality had been. It was hard to confess, but true, that in many respects my thinking about the spiritual life had been deeply influenced by my North American milieu with its emphasis upon the “interior life” and the methods and techniques for developing that life.

In fact, Henri reflected, he had fallen into a spirituality for introspective persons who have the luxury of the time and space needed to develop inner harmony and quietude. Very different from the attentive, urgent, disciplined focus of Dennie’s colleagues. Or of the Flying Rodleighs.

What do I want to say about the teamwork of the trapeze act? Henri asks himself now. Is beauty in its essence a shared spiritual endeavor? These artists have a desire for continual self-improvement, but they create beauty for others, and their act is lived out in teamwork and community. I’ve seen very clearly that all together form one body, as a whole. If one part of the body isn’t functioning, the whole body isn’t functioning. ♦

Excerpted from Flying, Falling, Catching by Henri J. M. Nouwen and Carolyn Whitney-Brown and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2022.

Selected Interview Highlights

On how she came to write the book (0:00–0:50)

Back in 2017, the publication committee of the Nouwen Legacy Trust got in touch with me because they knew I was a writer who knew Henri well. They said, “We’ve got this trapeze material, and we don’t know what to do with it. It doesn’t quite add up to a book, but it’s been sitting here for 25 years. Have a read and see what you can think of.” I went to the Nouwen Archives and dug around and read all I could find, and got fascinated with the project.

On how she approached “collaborating” with Henri to tell this particular story (0:51–3:25)

When I started working on it I realized there were two key mysteries that I didn’t have the answer to, and I don’t think Henri had the answer to. One was, why did the experience of the trapeze hit him that dramatically at that moment in his life? The other one was, why didn’t he write the book? Part of what my book does is it tries to create a framework where Henri himself can try to figure those things out: I can bring in writings—not just his trapeze writings, but other writings from the time and other things that seem connected to what brought him to that point in his life.

On what she learned about Henri as a writer through the process of shaping the narrative (3:26–5:16)

What I hadn’t really grasped was how much Henri wanted to write a different kind of book. He wasn’t going to carry on with the project until he found the form he wanted to write it in. I could really try to get on the inside of what he was trying to do. As a writer that was really fascinating to me, and it brought me quite close in feeling to Henri again. I think his urge to write a story was because he didn’t want to impart his ideas or thoughts to an audience. He wanted his audience to have his experience as much as he could.

On how Henri’s writing on the trapeze differs from his other published work (5:17–7:09)

It’s a very physical book, and it’s told as a story. Henri really holds back from drawing too many conclusions. He wants the reader to experience the joy of discovering their own insights. His other books start with an insight that he wants to share—that we’re all beloved, or that we can find ourselves in the Prodigal Son story. Very concrete things, almost always in the Christian tradition. This is a physical experience that’s outside of the usual, traditional Christian imagery that he’s so comfortable in.

On Henri’s ability to empathize with other people’s stories (7:10–8:04)

Imagining himself into other stories was one of the things that Henri did so well. If you think about him going to Selma [for the 1965 protest march organized by Martin Luther King Jr.], which is in this book, and picking up a young Black hitchhiker and suddenly finding that he’s in a world he hadn’t imagined where they can’t stop at gas stations, they can’t stop for food. He wasn’t expecting that. He imagines himself over and over again into different worlds. He really wanted to get into other people’s experience in a very nonjudgemental, very open, curious way.

On what elements of Henri’s character drew him so profoundly to the trapeze (8:05–9:51)

The Flying Rodleighs’ experience of him was as someone very free, kind of flamboyant, really happy. It released a kind of playfulness in him. One of the ways he describes the Flying Rodleighs so often is the fun they’re having together. He describes his response to the trapeze as “adolescent.” It touches something of that moment between childhood and adulthood when you become aware of your body, you become aware of your sexuality. You’re right on the verge of becoming an adult, and it’s disorienting and exciting. That’s what the trapeze takes him to, and he emphasizes that over and over.

On the ways that Henri saw the trapeze as a spiritual experience (9:52–11:23)

The trapeze is not about the individual body. It’s about the body in motion with other bodies. It’s about things the body can do with others that you could never do by yourself. You can’t fly if there’s no catcher. You can’t catch if there’s no flyer. You can’t even fall, in a way, if there’s no one to have helped set the foundations for you to fall safely. You need other people. Henri is interested in the Flying Rodleighs, in their discipline, in their structured life together. Their freedom is really tied to a lot of good communication and a lot of very hard work.

Henri Nouwen with Carolyn Whitney-Brown and her children, Rotterdam, early 1990s. Photo courtesy Carolyn Whitney-Brown

On how writing the book influenced her own spiritual journey (11:24–13:31)

I am now the same age as Henri was in this story. I kept thinking about his courage, renting an RV and traveling with the circus. I find myself really fascinated that he allowed this trapeze experience to just seize his imagination, and I find myself paying attention to what seizes my imagination, what are those moments in my life? And I hope readers do that, too. The question of listening and being attentive to what you respond to physically, what grabs your imagination. And then hold onto it and work on it and be really brave to walk straight into it: that I’ve been thinking about a lot.

On why Henri’s life and work continues to speak to so many people today (13:32–16:17)

I think it goes deeper than just his ability to write vulnerably and personally. I think it’s his ability to keep digging deeper, and pushing himself to ask a deeper question. He doesn’t just indiscriminately pour out everything; he really, really works on what’s helpful, what brings God into the world, how we become embodiments of God in the world. And he just keeps working on that. He doesn’t leave it at a superficial level. His message isn’t simple. He was a peacemaker. He cared deeply about social issues.

He was always open to what the next call would be in his life and was very brave about exploring what it would look like. I think that’s part of what makes him so enduringly interesting. He pushes us to push a little deeper, and to do that from a place of trust and grounding. For Henri that was a place of knowing that we come from God, that we return to God, we are beloved, that in a way we can’t make any mistakes that can’t be held within that big love. He really stayed well rooted in that and invites readers to stay rooted there, and then be able to live with quite a lot of courage, fun, community, discipline, excitement.

He didn’t want anyone to live a boring life. He really wanted everyone to get out there, trust ourselves, trust each other, and live in a way that really matters in the world with a lot of energy and joy and solidarity. ♦

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!