From Seed-Time to Maturity by Michael Centore

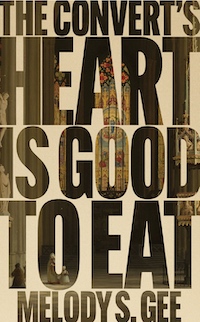

The Convert’s Heart Is Good to Eat

By Melody S. Gee

Driftwood Press, 2022

$9.99 34 pp.

Reading Melody S. Gee’s recent chapbook, The Convert’s Heart Is Good to Eat, I am reminded of Theodore Roethke’s assessment of his 1951 collection Praise to the End!: “Each poem is complete in itself; yet each in a sense is a stage in a kind of struggle out of the slime; part of a slow spiritual progress; an effort to be born, and later, to become something more.” Gee’s struggle is less propelled by anguish than pulled along by hope, and its “slime,” such as it is, takes the form of images of other integuments—membranes and husks, cocoons and cauls—that rend into new life:

Your early cells would

be anything. Some directive

says heart and not nail,

so the cells divide, eachsplit extinguishes lip, vessel,

iris, to build the heart’s walls.

You are separation, neither

pieced nor built. (“And So More”)

The emotional frisson of these lines comes from wondering whether the speaker is addressing a child in the womb or the specter of a newly emerging adult self—a poetic persona, perhaps, the latest creative correlative to an ongoing process of personal maturation, or the “convert” of the book’s title coming into being as spontaneously and mysteriously as a cell in the throes of mitosis. The possibility of multiple addressees between and among the poems, and within the poems themselves, is what gives the book its amplifications of meaning, and the slippages between these meanings open the space for Gee to explore themes of regeneration, recreation, and rebirth. A poem like “Conditions,” redolent with the mildewy fecundity of Roethke’s poems about his father’s greenhouse, does this by seizing the central image of a childhood memory and recapitulating it into insight:

In school we line beans into damp bags

to sprout. We gaze and prod them: break

and burrow without light. Andthey do.

Just when we feel the poem is safely situated in the world of reminiscence—a speaker looking back on the “little baggies among second / grade clutter” containing tangles of roots and stems—there comes a subtle shift in register:

By winter, I already know how to eat

my armor. Neither do I want to enter

the world under these conditions.What can come from a chewed hull,

from the body set free by its own

careful devouring?

This is not a child’s voice, nor is it an adult’s voice ventriloquizing the concerns of a child. Nor is it a poet describing an experience of childhood: we expect children to have vivid imaginations, but the interrogating spirit in evidence here, the assurance with which the voice moves through metaphor as easily as it makes connections between inner and outer worlds, demands another brand of self-knowledge, or at least a longing for self-knowledge, that only comes with age. What is happening in these stanzas—and why, to my ear, they touch the poem with an air of uncanniness—is the merging of the adult and the child into a singular moment of self-discovery. They were always merged, of course—that’s the paradox of time, that we both are and are not who we were—but here the insight becomes conscious, and the thrill for the reader is that we feel it move both ways: the poet has located the living image of the child that allows them to understand each other, and to understand together their shared process of growth—of conversion. This is the same double movement Octavio Paz saw as animating Wordsworth’s Prelude, where “the passage to maturity is also a return to childhood”; it is corroborated by something Gee herself says in an interview appended to the end of the book:

These poems are my trying to ask and answer the questions of what I am doing and who I am becoming in conversion. . . . I think I’m searching for a cohesive narrative that includes and perhaps explains this unexpected turn. I’m trying to see if the girl is the same since the convert was born, to see if the story is big enough to contain them both.

And elsewhere:

[T]he book is concerned with faith and identity because I’m living the tension of a change that is part of my life and my entire life. What does conversion mean for my past? What does it do to the “before?” Is there room for all the past and the present? Does a new ultimate concern mean a rejection of another?

By the time the poem slips out of the transtemporal moment I have tried to limn above and reestablishes itself in the past tense of memory, it seems to me that Gee has begun to answer her own rhetorical questions. “Weeks later we find the bags, slick / and rot-clouded”, the speaker reports, filled with “bloodless filaments / spiraling nowhere, pale as fingernails.” “Pale as fingernails” is an inspired comparison because it anchors the palingenesis motif in biology itself. Don’t think that this instance of regeneration is occurring solely in someone’s head, or even in their heart in its Semitic understanding as the seat of the emotional and spiritual life, the simile seems to imply—it is overtaking their entire body, down to the keratin that is continually expanding that body’s outer limits. The three concluding lines read as a retrieval, the poet resurfacing with the image of the bag like a diver clutches a pearl:

Every cell’s engine had waited for the light

we sealed out. Every multiplicationa miracle: instructions followed nevertheless.

Before going any further, I should mention that the “conversion” documented in these poems, and to which I have been making repeated reference, is a religious one, to Catholicism specifically. I haven’t felt the need to clarify this because conversion, in its generic sense, is already so close to the active principle of poetry. Both arrive unannounced yet not uninvited, uttering words that may feel foreign, even frightening—or no words at all, just the inexpressible intercessory groanings Paul heard in the Holy Spirit or the insistent incantatory rhythms that drummed the ancient epics into the minds of our ancestors. Both impart a feeling of dislocation that implies a discovery, for the poet as well as the reader: Where am I? How did I get here? How do I understand this, make meaning of it, and take it back into my life? In a way the poet’s subject is conversion, insofar as every poem, like every act of conversion, is a turning from one form of life to another—from thought to music, for instance, or from conventional grammar to the syntax of dreams. Even the turn from one completed or abandoned poem to the hope for or shape of the next represents a sort of conversion, in that the poet is allowing something she has made to make an impression on her, to change her, even, and revise her conception of who she is and how she sees, thinks, writes. Yeats got at something like this when he said that “one poem lights up another.” There is also the late Orthodox theologian Kallistos Ware’s response to an evangelical who asked him if he was “saved”: “I trust that by God’s mercy and grace I am being saved.” In poetry as well as faith, conversion is always in the present continuous.

With this in mind, let’s turn back to “Conditions” and its final three lines. Here they are once more:

Every cell’s engine had waited for the light

we sealed out. Every multiplicationa miracle: instructions followed nevertheless.

The instinct when reading through a religious heuristic would be to focus here on the bag sealed off from the light as a symbol of the hardened heart that won’t “let in” the light of conversion. This is fine, but seems to me a little pat and moralistic. It also places the onus on the would-be convert to create the conditions for her own conversion, which runs counter to the idea, hinted at elsewhere in the book, of conversion as a rapid and unexpected force that can’t really be prepared for, only ceded to—a calling, in Gee’s own words, to which one “keeps saying yes.” My mind instead goes to something that is not in the poem explicitly, but is conjured out of the elements with which Gee constructs the scene: an image of a child, perhaps the poet herself, studying the contents of the bag brought out into the light: the spindling roots and stems that were not there weeks ago but are there now. Who made them? It crystallizes a moment of wonder, that first sense of the delirious gratuitousness of nature.

“Just as the wind carries thousands of winged seeds,” Thomas Merton writes, “so each moment brings with it germs of spiritual vitality that come to rest imperceptibly in the minds and wills of men.” Setting aside Merton’s limiting use of gender, I think we are witnessing one such moment of spiritual vitality in this poem. The seed of awe has been planted in the seven-year-old observer, and it is this awe—and not, as it were, intellectual debates about the efficaciousness of faith—that first instills the religious impulse, the desire to formalize and ritualize our experience of the numinous so that we can both honor it and access it. I realize I am moving into speculative territory here, but I am tempted to revise my earlier claim that the convert has no role in creating the conditions for her conversion. By pushing this moment of the poem to its endpoint, we can infer how the smallest, most seemingly insignificant experience—Merton’s “germ” of spiritual vitality—can, when captured by the imagination that comes so naturally in childhood and that in adulthood may take the form of the writing of poems, contribute to a sacramental understanding of the world that leads to a spiritual practice. This impression is reinforced, with a twist, in the language of the poem’s end:

Every multiplication

a miracle: instructions followed nevertheless.

I think this communicates a particular truth about the experience of conversion. To tease out what that is, we’ll have to zoom in.

Every multiplication

a miracle: instructions

Closer:

a miracle: instructions

Closer still:

miracle: instructions

There. In those two words, hinged on that half pause of a colon, Gee renders like an ideogram the inevitable passage of internal conversion to the external proprieties of religious law. Whether conversion is a sudden inbreaking of understanding or a slow turning in the furrow of the heart, it carries with it shades of the miraculous: a whole new system of thought might emerge, or at least a way of apprehending the world; there is a new lens on life that might scan at once strange and familiar, inarticulable and thrilling, as precepts that seemed stable fall away from within. And then? Well, in the case of Catholic conversion, you have the Vatican, and the curia, and the catechism and canon law, and all the other juridical structures that keep the institution in place. Miracle: instructions. Granted, the latter is there in the service of the former, both to safeguard it and to imbue it with a communal spirit that prevents it from becoming a conversion sui generis, but the two have been in tension ever since Peter and Paul first debated the rules for admission of Gentile converts into the early church. This is why I hear in the silence of that colon the hiatus between the Resurrection and the Council of Jerusalem, which is to say between Christ and Christianity, that every convert must eventually come to terms with by reconciling within herself her place on both sides of the story. Gee has begun this lifelong process in these poems, and what Stanley Kunitz said of Roethke’s quest could well be said of hers: “In order to find himself he must lose himself by reexperiencing all the stages of his growth, by reenacting all the transmutations of his being from seed-time to maturity.” ♦

Michael Centore is the editor of Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!