The Lyric Forest by Frank Freeman

Trees: An Anthology of Writings and Paintings

by Hermann Hesse

Selected by Volker Michels

Translated by Damion Searls

Kales Press, 2022

$28 136 pp.

Anyone my age (62) and prone to the reading life will remember Hermann Hesse mass-market paperbacks, often available even in convenience stores, and their covers featuring angst-ridden German youth, especially the earlier works such as Demian (1910) and Beneath the Wheel (1906). (Oh, for the days when you could buy a decent work of literature in a 7-Eleven!)

These novels portrayed young men who suffer an Apollo/Dionysian split within themselves and wrestle to reconcile these two aspects of their souls with the bourgeois societies around them. Family and friends harp at them to get on with their lives and make money, but they want to find a way of life in which their split souls can be united. The Hesse protagonist knows one must “make a living,” but also knows that this life is, as Keats said, “a vale of Soul-making.”

Some of these novels focus on art—Gertrude (1910) for instance—others, such as Demian and Beneath the Wheel, on education, and yet others—Peter Camenzind (1904), Siddhartha (1922), and Narcissus and Goldmund (1930)—on religion. Steppenwolf (1927) portrays a midlife crisis extraordinaire, and Magister Ludi: The Glass Bead Game (1943), admired by Thomas Mann, André Gide, and T. S. Eliot, is a work of utopian fiction set in the 25th century and was cited in Hesse’s winning of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. Hesse also wrote essays, nonfiction, and many books of poetry, although he is best known in America for his novels.

All of these novels delve deeply into psychology and philosophy. As Hesse wrote, “Almost all the prose works I have written are biographies of the soul, monologues, in which a single individual is observed in relation to the world and to his own ego.”

Raised in a very religious household—his parents and grandparents were all full-time missionaries and/or pastors, some having served in India—he was a very rambunctious and hard-to-tame child, brilliant and talented. He lost his parents’ faith in Pietist Christianity, but never the religious context within which they had raised him. Though he embraced Eastern philosophy and religion, he never quite gave up his Christian roots.

Hesse clashed with political authorities during both World Wars—his biographer, Ralph Freedman, quotes him as writing to Romain Rolland: “The attempt . . . to apply love to matters political has failed”—and the Nazis banned his work. His family life was tumultuous and strained: he married three times, had four children with his first wife, and eventually was happy with his third wife, the art historian Ninon Ausländer. He lived most of his adult life in southern Switzerland in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino, primarily in Montagnola.

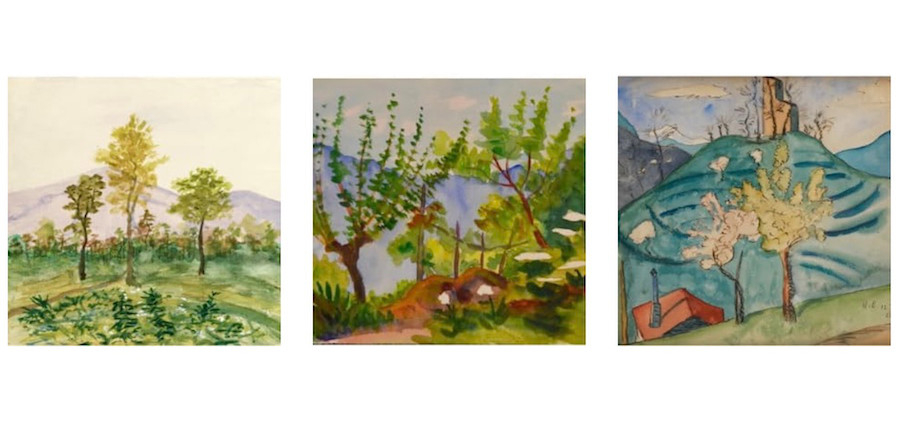

And that is where many of the 32 watercolors of trees featured in this beautiful little book were painted. For Hesse was also a visual artist. His paintings are not as skillful and profound as his writings, but they have given me much pleasure. The Oglethorpe University Museum of Art says of them, “His watercolors reveal an expressionist fervor, a Fauvist palette, and a style that often touched base with Cubism.”

This anthology, ably and lovingly put together by Volker Michels, the current executor of Hesse’s literary and artistic estate and the editor of his complete works, shows how big a role nature plays in his works, especially in the form of trees. Michels has harvested many beautiful and moving passages from Hesse’s essays, novels, and poems to accompany the images. The poems particularly were a surprise to this reader.

What struck me while reading this book was the sense of expanded time Hesse brings to his descriptions of trees. You feel as though you are a child again, with gobs of time to just sit and stare at trees, their bark, their leaves, their roots, their shapes. More than once, Hesse meditates on a tree that has been uprooted by a storm, what the tree meant to him over the years, what its absence means now, and whether he will have it replanted or not. If you absorb it slowly and deeply, this book can help slow you down so that you find yourself staring at the trees in your environs with more attention and thoughtfulness.

The first essay in the book, “Trees,” serves as pronouncement of the various themes that will follow:

Trees, for me, have always been the most compelling preachers. I worship and adore them when they live in families and tribes, in forests and groves—and even more when they stand alone. They are like solitary people. Not hermits who’ve stolen away from society out of some weakness, but great, lonely people, like Beethoven or Nietzsche. The world rustles in their uppermost branches, their roots rest in the infinite, but they do not lose themselves in either, they work with all the strength of their lives toward just one thing: fulfilling their own law that lives within them, shaping their own form, becoming their own selves. Nothing is more sacred, nothing more exemplary, than a strong and beautiful tree.

You see here that Hesse still has his feet planted in the soil of his upbringing—trees are preachers—but how the gospel has changed from one of serving God to one of God’s creatures fulfilling the “law that lives within them, shaping their own form, becoming their own selves.” The best way to serve God is by becoming oneself.

To give a taste of the poetry, I include two poems about branches: the first, “Flowering Branch,” from 1913, written when he was 36, the second, “A Broken Branch Creaks,” written in 1962, the last year of his life:

Flowering Branch

Constantly this way and that

The flowering branch flails in the wind,

Constantly up and down

My heart flails like a child

Between bright days and dark,

Between wanting and renouncing.

Until the flowers have blown away

And the branch is covered in fruit;

Until the heart, sated with childhood,

Has its rest

And confesses: it was full of pleasure, not for nothing,

This restless game of life.

A Broken Branch Creaks

Splintered, broken branch,

Still hanging year after year,

It drily creaks its song in the wind,

It has no leaves, no bark.

Bare and pale, tired of too-long

Life, of a too-long death,

How hard the sound, how dogged too,

Stubborn but secretly afraid:

Its song for yet another summer,

Yet another long winter.

In a concise yet profound afterword, Michels connects Hesse’s vision of trees with our own urgent need to conserve and learn from them. “The surface area,” he points out, “of the leaves on a large tree, roughly comparable to the area of a soccer field, produces about five tons of oxygen a year.” He also reminds us of the rich diversity of trees, the differences in their barks, trunks, leaves, branches, and fruits.

“Amid the hectic life of our cities,” he sums up, “trees for Hesse were like monuments to slowness and forbearance.” ♦

Frank Freeman’s work has been published in America, Commonweal, Dublin Review of Books, and the Weekly Standard, among others. He lives in Maine with his wife and four children, dog, cat, and four chickens. He hopes to have his books published some fine day.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!