“Cords of Human Kindness”: An Introduction to Small Christian Communities

This past June, Today’s American Catholic convened a listening session in response to the “Synod on Synodality.” A key point of our discernment was that people are longing for a deeper sense of community in their experience of faith. We discussed small Christian communities (SCCs) as a promising way to foster relationships and help participants be more proactive in learning about and living the gospel.

Encouraged by this discernment, TAC recently started a pilot program to host, promote, and network new and existing SCCs, including an SCC that grew out of the Saint Thomas More Catholic Chapel and Center at Yale University. This group has met weekly to participate in the vision of the SCC as outlined below. The experience has been fruitful for participants on many levels, both individually and collectively, and has inspired TAC to build out the program so that others may participate.

Our plan in the coming months is to assemble the tools—essays and events, readings and commentaries, access to online meeting spaces, and other materials—to assist those who wish to join an SCC or form and facilitate their own. It is our hope that these communities might renew a sense of belonging that is sometimes missing from larger institutional spaces and create those cells of solidarity and synodality so necessary for the future of the church.

What follows is a brief overview of the origins, methods, and intentions of SCCs, as well as additional resources. Please follow the developing support for SCCs on our website as we continue to expand this new initiative—Ed.

The Synod has revealed a hunger on the part of the people of God for more meaningful experiences of spirituality and prayer. “There are a variety of reasons that people give for leaving the Church,” the “Region XVI” Synthesis reported, “but the most primary one is that they were not being spiritually fed.” The National Synthesis sounded a similar note: “Members of all the dioceses also wish the church would do more to support their spiritual growth by exposing them to many aspects of the rich heritage of Catholic spirituality.” And the Continental Document, a summation of syntheses from all over the world, pointed expressly to the connection between synodality—the path of which Pope Francis has said “God expects of the Church in the third millennium”—and the work of contemplation:

However, to function in a truly synodal way, structures will need to be inhabited by people who are well-formed, in terms of vision and skills . . . This new vision will need to be supported by a spirituality that will sustain the practice of synodality, avoiding reducing this reality to technical-organizational issues. Living this vision, as a common mission, can only happen through encounter with the Lord and listening to the Spirit. For there to be synodality, the presence of the Spirit is necessary, and there is no Spirit without prayer (72).

Elsewhere, the Continental Document puts an even finer point on this, stating that “we must grow in a synodal spirituality that is based on attention to interiority and conscience” (84) and that “prayer and silence cannot remain extraneous” to processes of collective discernment and decision-making (86). Another document, “Towards a Spirituality for Synodality,” prepared by the Commission on Spirituality and released in advance of the Continental Phase, devotes itself entirely to the task of “outlining some central features and dispositions of a synodal spirituality” (1) and affirms that “synodality is not only a theology but a spiritual practice” (6).

It is clear from all of this that the tenor of parish life needs to change—not only to better facilitate the emerging synodal church that the authors of “Towards a Spirituality for Synodality” characterize as a “listening church . . . attentive to all the modalities of God’s self-communication” (25), but also to develop the critical and contemplative imagination necessary for such a renewed church to take root. “The parish, instead of being a communal expression of the great community, [has] tended to become just the local subdivision of the large organization,” wrote the late theologian Gabriel Moran, and his observation all too frequently jibes with the sense that parishes are more attuned to institutional efficiency than fostering dynamic, relational spaces where questions of faith can be grappled with in all of their complexity and paradox.

The concept of the basic ecclesial community (BEC) or small Christian community (SCC) is not a one-size-fits-all solution to this problem, but it can go a long way in adding a spiritual leaven to the existing parish structure, weaving together new relationships and providing a forum for people to study, discern, dialogue, and pray together in more intimate settings. SCCs take as their model early forms of church life in which members gathered locally, in small groups, to read or listen to scripture and articulate how it applied to both their personal situations and to the developing vision of Christian mission. Some version of the SCC has likely been present in all eras of church history, but the practice was more formally refounded in the years following the Second Vatican Council, particularly within Latin American and African countries. SCCs speak to the council’s directives for a more engaged laity and, as Fr. James O’Halloran and others have shown, a church that ever more closely images the interior correspondences of a unifying, sanctifying, and self-giving Trinity.

The Bible is at the center of the SCC, not so much in the form of “Bible study,” which can close the text off from the world in self-reference and confuse biblical literacy, important as it may be, for the whole of faith, but rather as a shared location to experience the Word of God, assimilate it, and find points of contact between it and the living context of the person and the group. The SCC becomes a sort of “school of prayer,” taking up the project of mutual spiritual edification touched on in the Continental Document: “We are a learning Church, and to be so we need continuous discernment to help us read the Word of God and the signs of the times together, so as to move forward in the direction the Spirit is pointing us” (100). It allows for those sorts of exchanges that are not often available in standard parish arrangements—either because logistically the parish is too large, or because the priest, whose time is already stretched thin with administrative commitments, may not be able to carve out space to facilitate such intentional gatherings. At the very least, and in the most practical sense, the SCC gives participants the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the readings prior to each Sunday’s Mass; though it is not mandatory, most SCCs follow the liturgical calendar in selecting the scriptural texts for each session, and the ensuing period of prayerful dialogue helps “till the soil,” as it were, for the heart to receive its verbal seeds in all their potential fecundity.

The SCC also functions in part as a support group, a place to exercise those injunctions of Paul in his Letter to the Romans: “love one another with mutual affection; anticipate one another in showing honor” (Rom 12:10) and, in the spirit of a shared commitment to realizing the beloved community, “let each of us please our neighbor for the good, for building up” (Rom 15:2). One thinks of the early Desert Father who spoke of the monks of his lavra as being like river stones: bumping up against each other, borne along by the current, they smoothed away each other’s impurities and polished each other’s surfaces. That “bumping up,” that movement, is representative of the work we do when we inspire and instruct, counsel and advise, support and embolden in our ongoing effort to “seek peace and pursue it” (Ps 34:14) through the contemplation and application of the scriptures. The words of Saint Ephraim the Syrian come to mind: “My brother, labor with him who asks you to learn to read, that he might be able to study the splendors of God, and thus you will bless His majestic name. And be assured that God will repay you for this labor of yours.” As do the words of another monastic who lived closer to our own time, the Trappist M. Basil Pennington, whose reflection in his daybook On Retreat with Thomas Merton succinctly encapsulates the spirituality of SCCs:

We need companions on the way and we need guides. We do not, in fact, hear much that we are told when we first encounter it—in either the spoken or written word—because we are not there yet. We can absorb so little at a time. We need companions and guides who repeat what we have heard, perhaps many, many times, until the moment when we can finally hear it, when we need to hear it. We also need companions and guides to encourage us. Because it takes courage to live up to what we hear, to do that to which we are called. It is very lonely, the encounter with the nothingness and sin from which we come. But we must go through this to come to the experience of the true self, which is the self in communion and union with God and others.

This brief introductory essay barely scratches the surface of the historical, theological, ecclesiological, pastoral, and pneumatological possibilities of SCCs, nor their sociological, institutional, and even political implications. There is a sizable if disparate body of SCC-related literature available that is calling out to be collated and synthesized, and new connections between SCCs and secular models of community organizing that might be made to help the church live out its gospel mission more fully and with greater nimbleness, transparency, and inclusivity. In a way the SCC functions as a kind of nexus or locus point for the various issues confronting a world of widespread institutional failure: namely, how we develop those networks of mutual aid, both material and spiritual, that will resist the corrosive commodification of life “with cords of human kindness, with bonds of love” (Hos 11:4). ♦

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic

Further Resources

- The North American Forum for Small Christian Communities (NAFSCC) is a network of diocesan and parish leaders dedicated to promoting and building on the mutual experience of SCCs rooted in the early church.

- The National Alliance of Parishes Restructuring into Communities (NAPRC) offers training, support, resources, and networking to parishes looking to restructure in a clear and deliberate way to stay focused on the Eucharist.

- Founded in 1976 as an office of pastoral renewal in the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey, RENEW has helped Catholics in more than 160 U.S. dioceses and 24 countries to form small groups for prayer, reading, and reflection. Their materials and training of lay leaders have been made available in more than 40 languages and in Braille.

- Small Christian Communities identifies itself as a “global collaborative website” with information and resources on SCCs from around the world. The site also features book reviews, links to online SCCs, and first-person accounts of experiences with SCCs.

- The website of the Association of Member Episcopal Conferences in Eastern Africa (AMECEA) features a timeline charting the history of SCCs in the region.

- An article from the March 4, 2020, edition of America looks at basic ecclesial communities in Latin America and how they assisted vulnerable victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

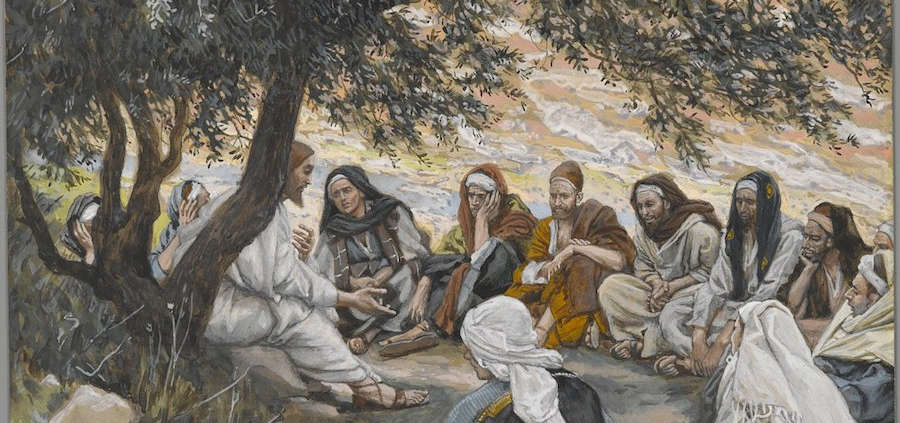

Image: James Tissot, The Exhortation to the Apostles, 1886–94.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!