Truth and Reconciliation: On the Work of David Kertzer by Tom Bishop

In 1822, the German historian G. H. Pentz wrote: “There is no better defense of the papacy than to unveil its inward being. If weakness is shown up you can reckon on a more friendly judgment through historical understanding than, as often until now, it is all kept secret and men are left to suspect what they will.” Putting these words into common parlance, we would say that sunshine is the best disinfectant.

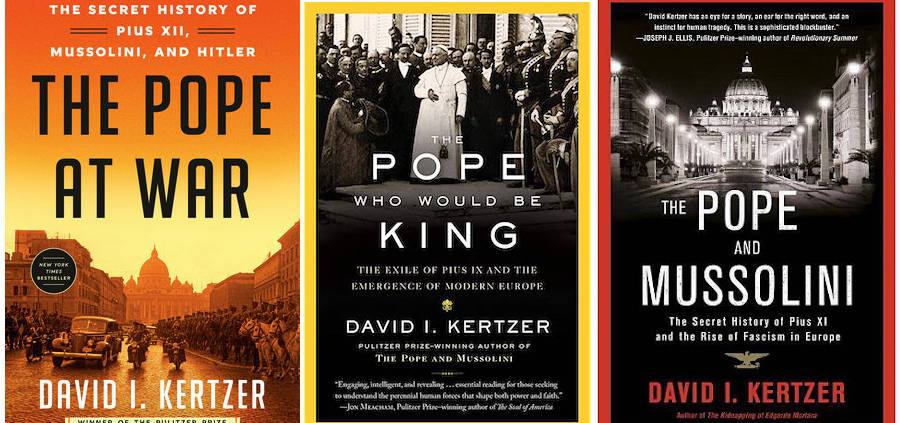

The Pulitzer Prize–winning author David Kertzer, a chaired professor of anthropology, social science, and Italian history at Brown University, is the author of the 2022 book The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler. As longtime personal friends, Kertzer and I have often talked of his special interest and knowledge regarding the history of the papacy’s treatment of the Jewish communities of Italy in the 19th and 20th centuries, and I have read his previous works on this topic. Born Catholic, this learning has been difficult for me.

Aided by his access to the Vatican archives opened by order of Pope Francis in 2020, as well as those of Germany, Italy, Great Britain, and the United States, The Pope at War is clearly a “disinfectant” to the misunderstanding and ignorance about the role of Pius XII during the reign of Nazism in Europe in World War II. Kertzer’s book has been favorably reviewed in the New York Review of Books, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the National Catholic Reporter, just to name a few, and less favorably reviewed in the more conservative sectors of the Catholic press, including the Jesuit magazine America.

In this work, Kertzer reports previously unknown dealings between Pius XII and Hitler through which they reached a sort of détente. Through emissaries specially selected for this purpose, they reached an accord that if Hitler would agree not to prosecute Catholics or destroy Catholic properties, and permit seminaries and Catholic schools to remain open in Germany and the conquered states, the pope would not speak out against Nazism and its many atrocities. Records uncovered by Kertzer reveal that at one point during these negotiations, the pope wrote: “We love Germany. We are pleased if Germany is great and powerful. And we do not oppose any particular form of government, if only Catholics can live in accordance with their religion.”

Many view this as a devil’s deal. Others, apologists for Pius XII, point to the primacy of his responsibility to protect Catholicism and to the many instances in which Italian Jews were given sanctuary under the pope’s leadership.

As an aid to understanding the inaction of Pius XII during the war, Kertzer notes the pope’s background as the former papal ambassador to Germany and later as the secretary of state under Pius XI, observing that the pope was more diplomat than pastoral leader, more concerned with global politics—particularly the threat of Communism—than the great moral challenges of Nazism as they related to the deportation of millions of Jews to their certain deaths.

Kertzer discusses at some length the pope’s failure to publicly object to Hitler’s invasion of Poland, the home of many Catholics, and, most pointedly, the pope’s silence when faced with the deportation of more than 1,000 Jews from Rome to their certain death. In poignant detail, Kertzer notes that the Jews had been rounded up and brought to a military college just a stone’s throw from the Vatican; their subsequent removal within days by truck was all in plain view of the residence.

In reciting these difficult tales, Kertzer makes no claim that the pope was anti-Semitic, but rather that his own diplomatic training, combined with his belief that Hitler was likely to win the war and his protectionist concern for the church, guarded any outward protest he could have made on behalf of the plight of the Jews under Nazi assault.

In reciting these and other instances of the pope’s silence, Kertzer draws a sharp contrast between Pius XII and his predecessor Pius XI concerning their willingness to condemn fascism. He notes that Pius XI had commissioned John LaFarge, a Jesuit noted for his anti-racist activism, to prepare an encyclical, Humani generis unitas (On the Unity of the Human Race), that condemned racism and anti-Semitism, and that the document had been delivered to the pope shortly before his death. As Kertzer reports, word of the encyclical’s imminent publication had spread, and many members of the church hierarchy were fearful of Mussolini’s reaction to it. Soon after the death of Pius XI in 1939, Pius XII saw to it that the encyclical was suppressed and never published. To Kertzer, and I think to any fair-minded reader, this is another example of the pope elevating political expediency over moral leadership.

Some may claim that Kertzer is simply another partisan in the debate over the role of the papacy during the Nazi era. I disagree. Rather, I believe his work presents an important perspective on a deeply disturbing aspect of the history of the church. Kertzer does not editorialize. His book is reportage, the work of a historian committed to a factual record. It should be viewed as contributing to a better understanding between Christians and Jews because it is only through knowledge that true reconciliation and, ultimately, harmony emerge.

Kertzer comes to his interest in his subject through family history and personal memory. In 1944, his father, Morris Kertzer, was the only Jewish chaplain on the Anzio beach as the 5th Army began its upward surge through Italy, ultimately liberating Rome from the Nazis. There, Rabbi Kertzer, together with Rome’s chief rabbi, Israel Zolli, joined in leading the first Shabbat service for Jews who emerged from hiding for this holy moment. Later, when Zolli converted to Catholicism and there was an outcry of objection from the Jewish community, Morris Kertzer stayed out of the fray, keeping his own counsel. And later, after the war, Morris Kertzer dedicated his rabbinate to interreligious understanding, serving for a time as the Director of Interreligious Affairs for the American Jewish Committee.

On balance, I believe the history of the papacy during Nazism must be told and understood in historical context. It is no secret that for years, the Catholic Church disfavored Judaism. Indeed, until Vatican II it was generally held by Catholic dogma that the Jews were condemned to perdition because they had caused the death of Christ. Until well into the mid-19th century, when Italy took over the papal states, Jews were ghettoized by the church, required from time to time to wear badges designating them as Jews and prevented from certain occupations and many aspects of normal societal life.

Happily, in 1965, the promulgation of Nostra aetate (In Our Time), the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, was tantamount to the announcement of a sea change in the church’s attitude toward Judaism. Nosta aetate expressly rejected the church’s history of contempt against Jews and instead proclaimed that “God holds the Jews most dear” and called for greater understanding and mutual affection between Catholics and Jews.

In my view, the good work of Vatican II in opening a corridor to greater interreligious understanding, the great decision by Pope Francis to open to scholarship the archival history of Pope XII during the Nazi era, and Kertzer’s works on the history of the papacy as it relates to the Jews of Italy are all of the same piece. The more sunlight, the more understanding, and, through knowledge and even difficult truths, the better the hope of true reconciliation in our troubled world. ♦

Tom Bishop is a semi-retired judge on the Connecticut Appellate Court. A graduate of the University of Notre Dame with a degree in history and Georgetown Law Center, he is also the author of a novel, The Good Priest, previously reviewed in this publication.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!