Wings of Desire by Frank Freeman

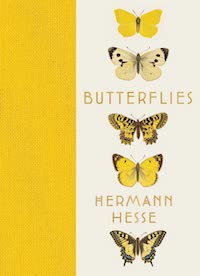

Butterflies: Reflections, Tales, and Verse

by Hermann Hesse

Selected by Volker Michels

Illustrations by Jakob Hübner

Translated by Elisabeth Lauffer

Kales Press, 2023

$30 136 pp.

When I first considered reviewing this book, I had some reservations. Butterflies? How about rainbows or bunny rabbits? Memories of my evangelical Christian youth, when the comparison of the newborn Christian to a butterfly emerging from the chrysalis was as overdone as singing “Kum Ba Yah” and “Pass It On” around the campfire, strobed through my thoughts. Even back then I had moments when I thought if I heard the first line of “Pass It On”—“It only takes a spark / To get a fire going”—I might run screaming into the forest surrounding us youthful ardent believers.

But then I remembered the Ray Bradbury story “Chrysalis,” collected in S Is For Space, which brings the simile to life in a new more evolutionary way, and Nabokov’s obsession with lepidoptera—“My pleasures are the most intense known to man: writing and butterfly hunting.” Then I read this collection of Hermann Hesse’s writings on butterflies, and my wonder at butterflies—real live ones, not refrigerator magnets—came back. And when I see a monarch, swallowtail, the numerous cabbage whites, the white and orange admirals, I realize how, despite the cloying images of butterflies that surround us, when a real one visits, everyone stops and stares. Butterflies induce in us a sense of wonder.

But then I remembered the Ray Bradbury story “Chrysalis,” collected in S Is For Space, which brings the simile to life in a new more evolutionary way, and Nabokov’s obsession with lepidoptera—“My pleasures are the most intense known to man: writing and butterfly hunting.” Then I read this collection of Hermann Hesse’s writings on butterflies, and my wonder at butterflies—real live ones, not refrigerator magnets—came back. And when I see a monarch, swallowtail, the numerous cabbage whites, the white and orange admirals, I realize how, despite the cloying images of butterflies that surround us, when a real one visits, everyone stops and stares. Butterflies induce in us a sense of wonder.

Hesse writes in the first selection in the book, “On Butterflies,” that nature is a “vibrant hieroglyphic script” which we could read “before the earth fell to technology and industry.” He goes on to say,

A sense of nature’s language, a sense of joy in the diversity displayed at every turn by life that begets life, and the drive to divine this varied language—or, rather, the drive to find answers—are as old as humankind itself. The wonderful instinct drawing us back to the dawn of time and the secret of our beginnings, instinct born of a sense of a concealed, sacred unity behind this extraordinary diversity, of a primeval mother behind all births, a creator behind all creatures, is the root of art, and always has been.

Or, as he writes a little later, quoting a line from Goethe: “I am here, that I may wonder!”

Experiencing this wonder, Hesse writes, helps us “briefly escape the world of separation and enter the world of unity, where one thing or creature says to the other: Tat tvam asi (‘Thou art that’).” This is not too far from the spirit of St. Francis, I would argue, though with an Eastern twist.

Hesse also points out that butterflies do “not live to eat and grow old; [their] sole purpose is to make love and multiply” and “glory in the celebration of procreation.” That is, butterflies are a celebration of pleasure attendant upon life. As Hesse notes (and here is where the well-meaning but shallow refrigerator magnets come in), “from time immemorial, humans have embraced the butterfly as an allegorical and heraldic figure of the soul.”

But what about all the killing of butterflies that hunters like Hesse and Nabokov do? Hesse argues that just as hunters are often in the vanguard of conservation, so butterfly hunters often do the most to make sure butterfly habitats are preserved. In so doing, they help the non-hunters, when they encounter them, experience “the great sense of wonder that precedes recognition and reverence.”

As with all things Hesse wrote about, however, butterflies are not only a sign of pleasure and life’s beauty. Or, rather, just because they are those signs, they partake in their temporality. Because they live and die so quickly and so brilliantly, they remind us of the fragility of life.

In a poem included in this volume, “Writ in Sand,” Hesse, after briefly referring to the apparently immutable stars, writes the following lines:

No, the greatest beauty to be found

Is that inclined to decay,

Death itself undelayed,

And then, that most precious thing: the sound

Of music that, no sooner played,

Hastens hence, dies away.

Butterflies, in a sense, fly like music through the air, alighting where they will; they are ephemeral.

But in their very beauty there dwells a darkness. In “Butterfly from Madagascar,” Hesse writes of receiving a glassed specimen of such a butterfly and how, after staring for a long time at its patterns and colors, it seemed to have “a smile of beauty.” But this beauty, when gazed upon too long, “turned suddenly wild and eerie.” This reminds me of Spenser’s “Bower of Bliss,” and of the character of Dmitri in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov talking about the enigmatic quality of beauty, how it can partake of both good and evil, lead to the Virgin Mary or “Sodom.”

Hesse sums up his version of this conundrum in the following manner:

Such is beauty, and always has been: loveliness reflected in a mirror that conceals the chaos behind it. Such is happiness, and always has been; a rapturous moment that begins to fade even as it ignites, caught on the breeze of mortality. Such is high art, the high wisdom of a chosen few, and always has been: a knowing smile at the abyss, a nod to suffering, playing at harmony even as the contradictions are locked in an eternal death match.

Part of the fragility of life mentioned above also has to do with the fraught nature of the humans who interact with butterflies. Their beauty gets entangled with our fallenness, our possessiveness. How we cling to things.

Such is the story Hesse tells in “The Giant Peacock Moth.” A friend of the narrator, Heinrich Mohr, tells of how he stole, accidentally mangled, and then returned a classmate’s beautiful moth. The classmate, Emil, was “a dullard,” “the Perfect Boy,” but Heinrich’s mother tells him he must confess and ask forgiveness before she will forgive him. He does so, and is rebuffed by the arrogant Emil, who says, “So, you’re one of those,” and refuses Heinrich’s offer of his own collection.

“That’s when I realized,” Heinrich tells the narrator, “you cannot make amends for what’s already ruined.” He goes on to tell of how he went to his room, “took out the butterflies, one by one, and ground them to dust and tatters between my fingers.”

The collection contains a more lighthearted story called “Indian Butterflies.” This describes Hesse’s adventures hunting butterflies in Kandy, Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. After dismissing some money-hungry children eager to receive pennies for every fly they point out, Hesse feels he has achieved victory: “Man will thus blindly go his way, fancying himself victorious when he has, in fact, been vanquished.”

Vanquished, that is, by a “comely, quiet man or gentleman with wavy black hair, doleful dark eyes and a fine black mustache” who speaks perfect English and is named Victor Hughes. Mr. Hughes knows a lot more about butterflies than Hesse and pulls collections from his coat pockets, pants, and from behind chairs in a hotel lobby. Hesse first refuses him, but Hughes wears him down. “Within days he saw to it that I had nothing civil left to say, but would simply buy his wares for ten rupees.” By the time he leaves Kandy he is half expecting Hughes to be hiding under his bed.

This volume on butterflies is a perfect companion to the Hesse anthology on trees reviewed previously in Today’s American Catholic. The executor of Hesse’s complete works, Volker Michels, has written a superb afterword about Hesse’s love of butterflies, and draws attention to how important they are to the web of natural life:

Butterflies are an essential part of the natural world, connected in myriad ways to the plants and animals around them. They pollinate flower and serve as food for little creatures like ants, frogs, lizards, and birds. Their larvae produce stunning amounts of excrement, which helps regenerate soil. The drastic decline in butterfly populations should serve as a warning sign to industrial nations whose prosperity comes at the cost of a natural world out of balance.

This volume also includes beautiful butterfly illustrations. The editors “sought out old, handcolored copperplate engravings, which, Hesse argues, ‘were far more lovely and, indeed, far more precise than any modern color prints.’” The engravings of Jakob Hübner (1761–1826) were chosen for this volume, and, along with marbleized endpapers, make it a handsome one indeed.

If you have ever worried that you don’t see things as when you were a child, or realized, as Hesse writes, “that it isn’t the flowers and lizards that have changed for the worse but, rather, my own spirit and eye,” this collection may help you to see butterflies again and give you an inkling of the wonder you had as a child. At least it has for me. ♦

Frank Freeman’s work has been published in America, Commonweal, Dublin Review of Books, and the Weekly Standard, among others. He lives in Maine with his wife and four children, dog, cat, and four chickens. He hopes to have his books published some fine day.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!