Flannery O’Connor: The Bottom Rail on Top by Nicole d’Entremont

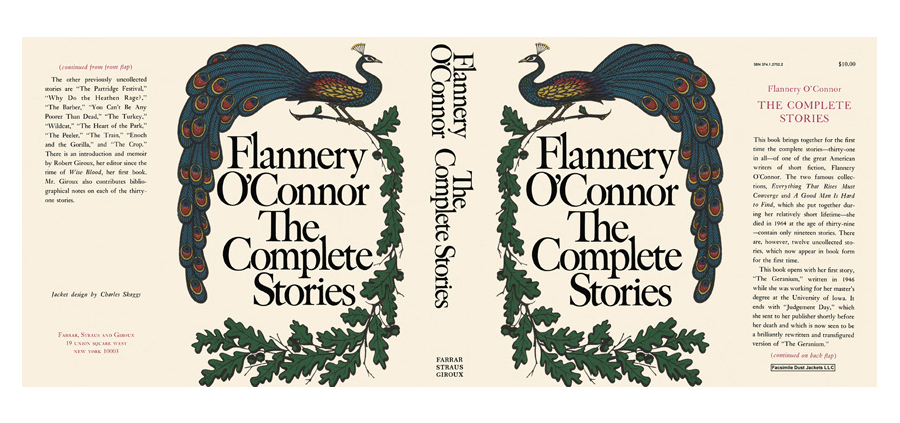

I’ve lugged my now tattered, hardbacked copy of Flannery O’Connor’s The Complete Stories for over 40 years from Maine to California to New Mexico and back to Maine. The cover is ripped and mended. The peacock’s plumage in the illustration is dulled, but the peacock’s black, piercing eye still skewers me as fiercely as O’Connor’s prose always did, direct and unflinching.

Have I read all the stories in that book? No. Are you crazy? Enough is enough. Maybe I’ll open another door if I feel the handle rattling in my hand and the title grabs me by the neck. I know when I enter O’Connor’s world, I will be a privileged interloper. If I do, I must enter it fully, not just with furtive peeks through a window. And if I’m caught only jimmying the window open a crack, I’d better watch out before it slams shut. Her world demands complete participation. This is the effect O’Connor has always had on me as a reader and as a writer.

Recently, I retrieved the 555-page edition of The Complete Stories from my bookcase where it rests, not cheek to jowl but near Virginia Woolf. I had just watched the PBS American Masters documentary, Flannery. It is a fine documentary in every way. Had its subject been alive to view it, I imagine her sitting through the whole thing and then commenting laconically about what she liked, what she found wanting. And, thus, be done with it.

We, on the other hand, are stuck with analysis. We drag everything out and dump it into the 21st century, with our religious-, race-, gender-, and class-based critiques riven with all the au courant political language. We parse O’Connor’s stories and the newly released private letters. It’s a perfect storm. Like an O’Connor short story, people say what they want to say and stand their ground. But, of course, no one can do it better than she did with her characters in the best, impossible, and sometimes unprintable language. Even screaming at God. Take Ruby Turpin in her story “Revelation”:

“Why me? she rumbled. “It’s no trash around here, black or white, that I haven’t given to. And break my back to the bone every day working. And do for the church.”

And, believe me, Ruby Turpin is just getting going. And this is getting going, this building up of a head of steam while whipping a snake of water from the hose she wields over the hog parlor, this calling out of God, “Who do you think you are?”

What to do with a writer as outrageous as that? No microaggression here, but full-bore macro. And a professed Catholic to boot. But that, to me, is her great ability. Her characters, whether white or black or freaks or idiots or criminals, whether earnestly and doggedly working, lounging, speaking a deluded or mad language, have real, observable joys and grievances. They work hard and do not prosper. They say things that we do not want to hear, but are truths in a language that we, sometimes, cannot abide. But O’Connor loves them, or she could not have written about them so convincingly. This is the great lesson I have learned from her. You have to love the people in the world you create no matter what they say.

Of relevance to many readers, though nervously acknowledged by some of them, is that O’Connor was a practicing and ardent Catholic. One of her more famous quotes was offered in a theological exchange with Mary McCarthy during a late-night dinner party that would have been exquisite to observe: O’Connor, Elizabeth Hartwick, Robert Lowell, and McCarthy and her husband Bowden Broadwater all around the same table. O’Connor and McCarthy must have been oil and water together, but don’t throw down a match.

In Paul Elie’s thoughtful and beautifully written book, The Life You Save May Be Your Own, one of the writers he profiles so artfully is Flannery O’Connor. He lends the reader a seat at the table at that dinner party with words that O’Connor later wrote to a friend:

We went at eight and at one, I hadn’t opened my mouth once there being nothing in such company for me to say . . . Having me there was like having a dog present who had been trained to say a few words but overcome with inadequacy had forgotten them. Well, toward morning the conversation turned on the Eucharist, which I, being the Catholic, was obviously supposed to defend. Mrs. Broadwater [I’m sure O’Connor relished using that formal appellation] said when she was a child and received the Host, she thought of it as the Holy Ghost, He being the most “portable” person of the Trinity; now she thought of it as a symbol and implied that it was a pretty good one. I then said, in a very shaky voice, “Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it.” That was all the defense I was capable of.

Given O’Connor’s penchant for manifesting the incredible as credible in her work, why wouldn’t the mystery such as the physical transformation of ordinary bread and wine into the actual body and blood of Christ be viewed in any other way? It would be accepted or denied. But never diluted.

Today, maybe especially today, any discussion of Flannery O’Connor has to include the question, “Was she a racist?” It just screams at you. It is mostly a discussion between academics, and so those of us who are not academics are sheltered by our ignorance concerning the various lines being drawn for or against. I am a fiction writer and a reader. I am a slow reader and a choosy one, and I often read the same book and the same stories over and over. This has never helped me out academically, but it gives me pleasure and, sometimes, a keener understanding with discoveries sharpening over time. I don’t think Flannery O’Connor thought of herself as a racist, but she did admit clearly to being a segregationist, and so I take her at that word.

She makes this designation in a letter that Elie references both in his article in the New Yorker (“Everything That Rises,” June 22, 2020) and again in a follow-up article in Commonweal (“Confronting Flannery O’Connor’s Racism,” August 12, 2020). The evidence is clear in O’Connor’s letters to her friend, the playwright Maryat Lee:

You know, I’m an integrationist on principle and a segregationist by taste anyway. I don’t like negroes. They all give me a pain and the more of them I see the less and less I like them. Particularly the new kind. (May 3, 1964)

And who are these “new kind”? They are, as O’Connor explains in a subsequent letter to Lee, “the philosophizing, prophesying pontificating kind” (May 21, 1964).

The statements are pure, unvarnished O’Connor, but as I read them, I don’t see George Wallace wagging his beefy finger and poking me in the eye, drawing a line in the sand, extolling the great Anglo-Saxon South to rise up with his cry: “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever.” I hear, instead, O’Connor acknowledging that she’s caught between a higher motive, the principle of integration, and her own desire to be left alone to enjoy company she prefers—let the chips fall where they may. Obviously, they have not fallen in her favor, at least given some political legislation, and that is good. I’m quite certain she would not have relished seeing my smiling 23-year-old face when I visited the South to urge my white brothers and sisters to repent the error of their ways, just as I certainly breathed a sigh of relief that I never had to spend any time with them while I was there.

If an imaginary trial were to be held on this issue, I think witnesses both for defense and prosecution should be drawn from the characters in O’Connor’s literary work. This would certainly make for lively testimony and, I think, provide more accurate information as to the motivation and conduct of the author in question regarding the charge of racism. I do rather suspect that the result would be a hung jury, just as it is today.

Sometimes, as a fiction writer, the characters you bring forth on the page say and do ghastly things, things you do not want to hear them say or do. When my characters have done that, my impulse is to push away from the table and go for a walk. That is exactly the impulse I am having now. But I have learned from Flannery O’Connor to let the characters say and do what they want because it’s them, caught just as I am, in the human condition, and it’s how they figure life out.

At the conclusion of “Revelation,” one of the last stories O’Connor wrote and revised in her short 39-year-life, we behold the middle-aged, land-owning, all-around-well-dispositioned solid citizen Ruby Turpin beginning her final assault on God: “Go on, call me a hog,” she challenges. “Call me a hog again. From hell. Call me a wart hog from hell. Put that bottom rail on top. There’ll still be a top and a bottom.” Then that last wail: “Who do you think you are?”

Ruby stands there with the sunset coloring the field and the sky crimson. O’Connor has her raise her hands from the side of the hog pen in a gesture described as “hieratic and profound.” A visionary light settles, and she sees before her in the sky “a vast swinging bridge extending upward from the earth through a field of living fire.” Upon that bridge march at the head of the line all the losers, all the disrespectables, the unkempt homeless beleaguered hordes lurching out of step towards heaven, all the white trash and the blacks and the lunatics and the freaks, all jumping and frolicking while those of us (perhaps ourselves)—the good, solid, respectable, little-bit-of-this, little-bit-of-that, church-going, temperate (oh, maybe a drink now and then) tidy, responsible inhabitants—inch slowly forward (though shocked) with our privileged, but now altered (considering our shock) demeanor, bringing up the rear. Maybe this is the necessary second baptism, this vision of the final place for our lot, solidly positioned at the rear of the parade before the gates are parted.

Nicole d’Entremont is a teacher and writer who lives on Peaks Island, Maine. She is the author of two novels, City of Belief and A Generation of Leaves. A short story, “Fives,” will be published this spring by Littoral Books in North by Northeast 2: New Short Fiction by Writers from Maine and New England.

Wow! A first reading doesn’t do it – needs to be relished. Will take the time that it deserves – maybe during a sleepless night…