America’s Original Sin: Opportunity for Metanoia by O’Neill D’Cruz

What you did to the least of my brethren, you did to Me.

– Matt 25:40

Racism is often referred to as “America’s original sin.” Does this conjunction of racism, region, and religion form an unholy trinity, or signify missed opportunity for a long-awaited metanoia? Let us examine the evidence (along with our conscience) for the former and then consider the latter proposition.

In Matthew 11:12, Jesus states: “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and the violent take it by force.” Is Jesus using rabbinical hyperbole, or postulating that humankind engages in perpetual violence to establish earthly kingdoms, thus violating the kin-dom of the kingdom of Heaven?

Theological justifications are important and necessary to avoid moral dilemmas posed by crimes against humanity. In Faith in the Face of Empire, Palestinian religious scholar Mitri Raheb writes that “empires create theologies to justify their occupation.” We are familiar with Joshua, who claims divine support for militant nationalism to “take possession of the land . . . and destroy” seven other tribes (Josh 24:8-13). As a latter-day Joshua, Constantine conflated the Cross of Christ with the sword of conquest. A more recent example is Nazi Germany: Hitler (who was a Catholic) signed the Reichskonkordat with the Vatican, gaining implicit religious support for the neo-Aryan Third Reich with its genocidal and white supremacist policies. For centuries, Crusades were the theologically justified Christian version of military expeditions and conquests. Later, a Eurocentric church adapted the military tactics and language of Deuteronomy 20:10-18 in the Doctrine of Discovery (DOD) papal encyclicals of the 15th century to provide theological justification for slavery, colonization, and genocide.

America, in its turn, justified occupation of the New World by European settlers using DOD principles (we now use the same acronym for Department of Defense!). BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, Persons of Color) communities remind us that the Three-Fifth Compromise, Manifest Destiny, Monroe Doctrine, Indian Removal Act, and Chinese Exclusion Act are rooted in the political and economic precedents of European imperialism and theological justifications of Eurocentric Christianity. So while the Creator may have endowed humankind with inalienable rights, the life of the red, the liberty of the black, and the pursuit of brown and yellow folk were “expedient . . . rather than the nation perish” (John 11:50).

Within the American Catholic Church, voices against unholy alliances between racism, nationalism, and religion were raised frequently by BIPOC communities, but rarely heard or heeded. Mission schools that separated Native children from their communities, a slave economy that supported clergy and the congregation, and the exclusion of BIPOC Catholics from religious and fraternal orders are well-known examples of such alliances between racial politics and church policies. Catholics were not the only Christian denomination involved in these alliances, but one must concede that there was nothing catholic about them. In matters of Spirit, spirit matters!

In case we are tempted to wash our hands like Pilate of old and exempt ourselves (Matt 27:24), Christian scholars remind us that our blindness and our sins of ignorance remain (cf. John 9:41). In White Too Long (whose title is derived from James Baldwin’s timeless phrase), author Robert Jones outlines the present-day legacy of white supremacy in American Christianity. In Undoing the Knots, Irish Catholic Maureen O’Connell covers her own family history of five generations of white American anti-blackness. BIPOC perspectives are presented in Cyprian Davis’s The History of Black Catholics in the United States, Vine DeLoria’s Custer Died for Your Sins, and Bryan Massingale’s Racial Justice and the Catholic Church. Massingale also points out episcopal blind spots in Open Wide Our Hearts, the 2018 USCCB pastoral letter against racism.

♦ ♦ ♦

Enough said about unholy alliances. Polemics create schisms while possibilities hold the promise of transformation. So let’s turn to the other proposition—missed opportunity—and consider what metanoia looks like in our lives, families, and faith communities.

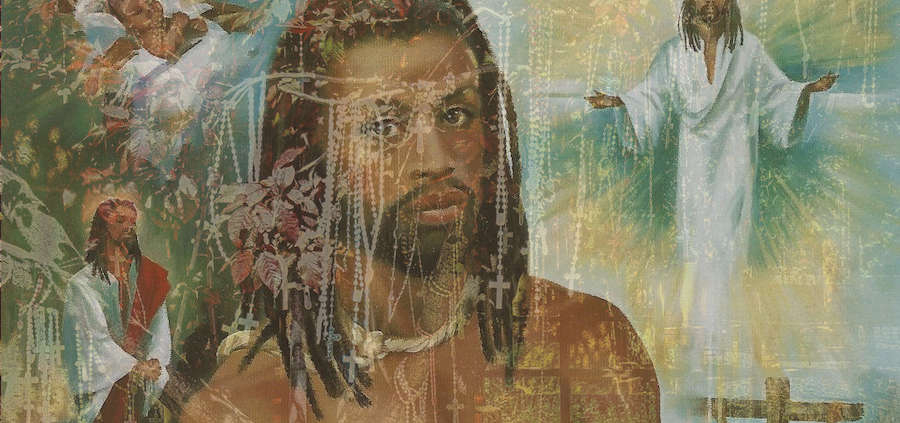

Let us first recall that Jesus was a brown-skinned Palestinian Jew whose family fled state-sanctioned violence and later relocated to a remote outpost of an occupied territory to avoid being victims of unfair and cruel political mandates (Matt 2:13-23). The psalms and the rosary provide time-tested means to pray the life and Passion of this color-rich Jesus. Jesus’s life story, prayed through the various mysteries of faith, vividly portrays the realities of BIPOC communities in modern-day America and opens up opportunities for metanoia.

We begin by listening and meditating on a psalm of communal lament from BIPOC members of the Mystical Body of Christ. The psalm is composed from the book of Lamentations in a standard format: greeting, lament, request, and trust.

O Lord, remember what has befallen us; look, and see our nation’s/church’s disgrace (Lam 5:1).

On our necks is the yoke of those who persecute us; although we are exhausted, we are afforded no rest (Lam 5:5).

“Go away! You are unclean!” the people shout. “Keep away! Do not touch us!” Wherever we flee, the people cry out, “You cannot stay here any longer!” (Lam 4:15)

The people no longer assemble at the city/church gate; the young have given up their music (Lam 5:14).

Joy has vanished from our hearts; our dancing has turned to mourning (Lam 5:15)

Continually we strain our eyes, looking in vain for help. We wait and watch endlessly for a nation/church that refuses to aid us (Lam 4:17).

This is why we are sick at heart; because of this our eyes have grown dim (Lam 5:17).

Why have you ceased to remember us? Why have you abandoned us for so long a time? (Lam 5:20).

Restore us back to you, O Lord, and we will return. Renew our days as we had of old (Lam 5:21).

Next, the mysteries of faith guide us in the rosary, as we walk in the shoes of our BIPOC brothers and sisters and look with their (and Jesus’s) eyes into their lives. Each decade covers a different aspect of the burdens of racism that evoke the psalm of communal lament. We do not truly pray this rosary unless we P.R.A.Y. (Ponder, Reflect, Act, Yearn) with “all our strength, all our heart, all our being” to “love our (BIPOC) neighbor as ourselves” (adapting Mark 12:33 and Luke 10:27; derived from Deut 6:5 and Lev. 19:18).

♦ ♦ ♦

First Decade: Birth of Jesus

Ponder: There was no room for them (Luke 2:7).

Reflect: I was a stranger, and you welcomed me (Matt 25:35).

Two thousand years later, in the richest nation in the world, disparities in social determinants of health persist and infant/maternal mortality rates are disproportionately higher within BIPOC communities.

Act: What opportunities can we identify, create, and participate in to make room for a BIPOC infant Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, who are still looking for a warm welcome in our communities?

Yearn: Dedicate to the Lord every newborn that opens the womb (Exod 13:12).

Second Decade: Agony in the Garden

Ponder: He found them asleep (Mark 14:37).

Reflect: Are you still sleeping? Behold, the hour is at hand (Matt. 26:45).

Like the apostles of old, we are still asleep while BIPOC communities are in agony to the point of being “sorrowful unto death” (Matt 26:38) as a result of institutionalized and interpersonal racism. Unable to “keep watch for an hour” (Matt 26:40), we end up betraying BIPOC Jesus actively (Judas), passively (the apostles in Gethsemane), by refusing to acknowledge (Peter), or, worst of all, fleeing from the problem! (“All the disciples left him” [Matt 26:56]). Isn’t now the time to “keep our eyes open” (Matt 26:43)? Or do we claim to be “color-blind” while we remain in denial of implicit bias in our lives and systemic racism in our institutions, or just walk away, adding the violence of silence as another insult to the injury of racial injustice?

Act: Do we build relationships with BIPOC communities, or remain apart? If we work among BIPOCs, who determines priorities, sets the agenda, controls the funds?

Yearn: Open my eyes so that I may see clearly (Ps 119:18).

Third Decade: Scourging at the Pillar

Ponder: Pilate ordered that Jesus be scourged (John 19:1).

Reflect: What evil has he done? I have not found in him any crime that deserves death. Therefore, I will have him scourged (Luke 23:22).

Even though he had committed no crime, Jesus was scourged to appease the masses—sound familiar? It does to BIPOC communities, whose ancestors carried for centuries the burden and wounds of the scourges of slavery, colonization, genocide, and abuse of power. Today, these scourges continue in their more refined forms as human trafficking, broken treaties, school-to-prison pipelines, and racially discriminatory policies and practices. Therein lie innumerable opportunities to prevent and heal the wounds of racism.

Act: The models of the Good Samaritan and Simon of Cyrene, both outsiders for pious folk of the time, remind us that the way to enter the kingdom of Heaven is orthopraxy, not orthodoxy (Matt 7:21). How well do we walk the talk? Do we “smell of the sheep”?

Yearn: Is this not the fast I (ought to) choose, to loose the bonds of injustice? (Isa 58:6)

Fourth Decade: Death on the Cross

Ponder: Jesus cried out . . . and breathed his last (Mark 15:37).

Reflect: Jesus, whom you had killed by hanging him on a tree (Acts 5:30).

If lynching produces “Strange Fruit,” in the language of the Billie Holiday song, then “by their fruits you will know them. Do people pick grapes from thorn bushes, or figs from thistles?” (Matt 7:16) Jesus warned his disciples that “They will expel you . . . those who kill you will think they are offering worship to God” (John 16:2). How do we respond today to such terminal acts of worship?

Act: Jesus was thirsty before he breathed his last, and that thirst for justice is unquenched till we create opportunities and work to “repair the breach” (Isa 58:12).

Yearn: Lord, when did we see you thirsty . . . and not minister to you? (Matt 25:44)

Fifth Decade: The Transfiguration

Ponder: He was transfigured before them (Matt 17:2).

Reflect: This is my beloved son, with whom I am well pleased (Matt 17:5).

We are familiar with John 3:16: “For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son.” Perhaps Psalm 2:7 is less familiar: “He said to me, ‘You are my son; this day I have begotten you.’” What if the significance of the Transfiguration is to serve as a catalyst for metanoia by revealing to each of us our spiritual ignorance and inheritance— “Do you not know that you are a temple of God and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?” (1 Cor 3:16) Or will we “not be persuaded even if someone should rise from the dead?” (Luke 16:31)

Act: Ask not what God can do for me; ask can I do “something beautiful for God,” as Teresa of Calcutta said. What can we do for the Suffering Servant transfigured as (even and especially) Black, Indigenous, or Persons of Color? Answer this, then do it!

Yearn: “Rejoicing . . . in his inhabited world, and delighting in the human race” (Prov 8:30-31).

♦ ♦ ♦

In the sacrament of reconciliation, Catholic tradition has made sacred—sacred-ment—the work of spiritual healing. In secular settings, the same work is done through the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) process at community and national levels. We know that both the sacramental and secular work follows a five-step process (the “five R’s”): recollection, recitation, repentance, restitution, and resolution. We become aware of our progress toward spiritual healing by individual and collective process mapping. While paths and progress may differ as we do this work, we meet each other at the final step around a common resolution:

When race and religion collide

And cast a color-rich Christ aside

Pray our actions help decide

Where charity and love reside

So if we want to join Wisdom in “rejoicing and delighting in the human race,” we would be wise to “work for justice, be compassionate, and walk humbly with God” (Mic 6:8). What could be more catholic? ♦

O’Neill D’Cruz retired once from academic clinical practice as a pediatrician and neurologist, a second time from the neuro-therapeutics industry, and now spends his time caring, coaching, and consulting from his home in North Carolina, known locally as the “Southern Part of Heaven.” He is a wounded healer who works to heal the wounded, in order that All Shall Be Well.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!